On 25 June 1950 six North Korean Infantry divisions, supported by large armor and artillery forces, crossed the 38th parallel and invaded South Korea. Much of the world was caught off guard. The Coast Guard’s involvement would be gradual and the duties assigned would be extensions of peacetime functions.

On 25 June 1950 six North Korean Infantry divisions, supported by large armor and artillery forces, crossed the 38th parallel and invaded South Korea. Much of the world was caught off guard. The Coast Guard’s involvement would be gradual and the duties assigned would be extensions of peacetime functions.

By direction of the Commandant a comprehensive description of the functions the Coast Guard expected to perform after World War II had been developed by a planning committee headed by RADM James Pine. The mission statement outlined the proposed peace time duties which included maintaining a military readiness to function as a specialized service with the Navy in time of war. In 1947 the Chief of Naval Operations, in recognition of the mission statement, suggested that the war time functions and duties assigned should be those which are an extension of normal peacetime tasks. Coast Guard units would be utilized as organized Coast Guard units rather than indiscriminately integrating them into the naval establishment. The Coast Guard was not transferred to the Navy during the Korean Conflict.

A Coast Guard contingent, for the purpose of establishing a Korean “Coast Guard” was set up in 1946. In 1948, when the Koreans decided this was

to be a Navy in lieu of a “Coast Guard,” the active duty personnel were replaced by retired officers to continue with the training of the nascent naval force. The training liaison was in progress at the time of the invasion. On 9 August 1950 President Truman signed an executive order implementing the Magnuson Act which charged the Coast Guard with ensuring the security of the United States ports and harbors. This reinstated a duty carried out by the Coast Guard during both World Wars. The most immediate problem in implementing these duties was the lack of personnel. The World War II reserve program had been emasculated at the end of the war and, for practical purposes; a functioning Coast Guard reserve did not exist. A supplemental appropriation provided the immediate increase in financing necessary to implement an organized reserve. The budget for the following years permitted the Coast Guard to adequately address the new and expanded demands. In July of 1951 a Coast Guard port security helicopter detachment was established for the New York City port area. The “police action” was in Korea but the “Cold War” with the Soviet Union was on and the Soviets supported North Korea. The threat of possible sabotage was a prudent concern. The detachment, under the command of LCDR Dave Oliver, had three Bell HTL helicopters and was supported out of the Brooklyn Air Station. More hours were flown than had ever been flown by Coast Guard helicopters before. The daily patrols could quickly spot anything that was not normal and radioed the information directly to the police department, the fire department, or other concerned agencies. The effectiveness of the patrol led both the New York City police department and fire department to obtain helicopters for their own use.

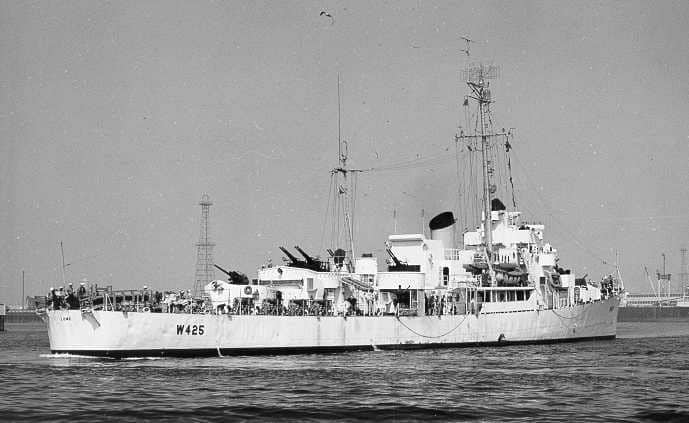

Coast Guard cutters manned two Ocean Stations in the Pacific prior to the outbreak of the Korean Conflict. At the request of the Navy three additional stations were added in the North Pacific. These stations provided complete weather data and greater search and rescue coverage for the growing trans-pacific merchant and military traffic generated by the war. Most all of the war material bound for Korea went by ship but nearly half of the personnel went by air. In mid 1951 the first of twelve former Navy destroyer escorts were made available to supplement the existing cutter fleet. In order to keep the ocean stations operational and perform search and rescue duties it required 22 coast Guard Cutters in constant rotation. A typical tour was composed of arriving at Midway Island for three weeks SAR standby, three weeks on Ocean Station Victor midway between Japan and the Aleutian Islands, three weeks on SAR standby at Guam, two week “R and R” (Rest and Recreation) in Japan, three weeks on Ocean Station Sugar, three weeks on SAR standby Adak, Alaska, and then back to home port.

The Coast Guard also supported the war effort by manning and operating nine LORAN stations throughout the Pacific. LORAN was the primary navigation system for ships and aircraft. One of the nine was the newly constructed and located on the Korean peninsula itself.

In 1952 the Navy also requested that the Coast Guard provide aircraft search and rescue capability. Two air rescue detachments were established; One at the newly reopened Naval Air Station at Midway Island; one at Wake Island. The Midway air detachment had a P4Y-2G and a PBY. Aircraft and aviation personnel were permanently assigned as part of the SAR Group. Ocean Station Vessels would rotate through Midway Search and Rescue duty for consecutive three week periods. The aircraft and cutters worked together as a unit. Wake’s Group Commander had an 83 footer permanently assigned. P4Y-2G aircraft and crews were supplied on a monthly basis from Barbers Point. Several Ocean Station vessel records show three week standby duty at Adak. A Coast Guard SAR air detachment at Adak, Alaska has been mentioned in several papers but no particulars have been located to date to substantiate this. The air detachment aircraft were primarily engaged in the intercept and escort of military and commercial aircraft that had experienced engine failures. The reason for intercept was that if conditions deteriorated the position of aircraft in distress would be known and the escorting aircraft could drop additional rafts and survival equipment to those in the water. In addition to SAR training exercises, searches for missing or down aircraft were conducted jointly with the Coast Guard cutters when assigned to SAR support duties.

Search and Rescue capabilities were also upgraded at the existing Coast Guard air detachments at Barbers Point, Hawaii; Guam; and Sangley Point in the Philippine Islands. Guam acquired an additional P4Y-2G and worked with the Ocean Station SAR Standby cutters. Two PBM-5Gs and a JRF were assigned to augment the PBY-5As at Sangley Point. The Coast Guard Cutter Vance, WDE 487, was assigned to the Commander Philippine Section.

The most dangerous of the search and rescue missions undertaken by the Coast Guard took place off the coast of mainland China in early 1953. Communist Chinese forces shot down a Navy P2V in the Formosa Strait while on a covert patrol of the China coast. The Coast Guard air detachment at Sangley Point responded to the call for assistance scrambling a PBM-5G Mariner seaplane. In command was Lt. John Vukic, one of the most experienced seaplane pilots in the Coast Guard. The initial PBM-5G was followed by a second PBM-5G piloted by Lt. Mitch Perry as back-up. Upon arriving on scene the P2V crew was located floating in rafts close to shore. The seas were observed to be between 12 and 15 feet making an attempted landing extremely hazardous but with nightfall closing in and almost certain danger of hypothermia the decision was made to attempt the landing. A successful landing was made and 11 survivors in the first raft were brought aboard and the jet-assisted take off bottles (JATO) were attached for use during take-off. Two survivors in a second raft had been swept ashore and captured by the communist forces. With a wind at 25 knots and the seas rising the take-off was attempted. The take-off progressed well and the JATO bottles were fired. It was at that critical moment that the left engine failed. The plane slammed into the sea and broke up. The second PBM-5G on scene circled and dropped a series of flares. The surviving crewmembers were picked up later that night by the Navy destroyer USS Halsey Powell. Four Navy and five Coast Guard personnel perished in the crash.

With the signing of the cease-fire on 26 July 1953 the Coast Guard began demobilization. The Destroyer Escorts were returned to the Navy and the air detachments at Wake Island, and Midway Island were closed. The air detachments at Barbers point, Sangley Point and Guam were returned to peace time complements.

The Coast Guard almost doubled in size from its 1947 low of just over 18,000 men and women until June 1952 when 35,082 officers and enlisted personnel served on active duty. The service demobilized but would never again return to 1947 levels. The role the Coast Guard played in the Korean War was vital but rather obscure. Future Commandants would address this issue. Some ten years later, Commandant E.J. Roland stated that he felt it was absolutely imperative that the Coast Guard become actively involved in a combat role in the Vietnam Conflict; otherwise it risked its status as a Military Service.