The aircraft and the cutter were teamed for the first time in 1936 when the first of seven Treasury Class 327 foot cutters was commissioned. A request had been made in 1933 for fast cruising cutters of 300 feet capable of carrying airplanes. Funding was provided under the National Industrial Recovery Act and construction began in 1935. The emphasis on airplane-carrying capability for the 327s was a direct result of the great strides being made in aviation at the time. In the application for funds to build the ships there was a statement that “certain cutters will require equipment of novel design to undertake rescue and assistance work for aircraft flying the ocean traffic lanes.”

The need for these cutters was three-fold. Air passenger traffic was expanding both at home and overseas and the Coast Guard believed that cutter-based aircraft would prove to be essential for future search and rescue situations on the high seas. Opium smuggling was increasing on the West Coast and freighters from the Orient dropped the drugs far offshore in watertight containers which were picked up by small fast boats for the run to the coast. A large cutter with extensive cruising capabilities carrying its own aircraft was looked upon as a solution. The third reason, which proved to be very productive, was the cutter-aircraft team in Alaska. For many decades following the purchase of Alaska the Coast Guard had enforced territorial law, fishing treaties, provided medical services, and assisted those in distress. The aircraft was able to provide rapid medical evacuations and effectively search vast areas for both rescue activities and law enforcement purposes. A patrolling cutter that had its own aircraft was very effective.

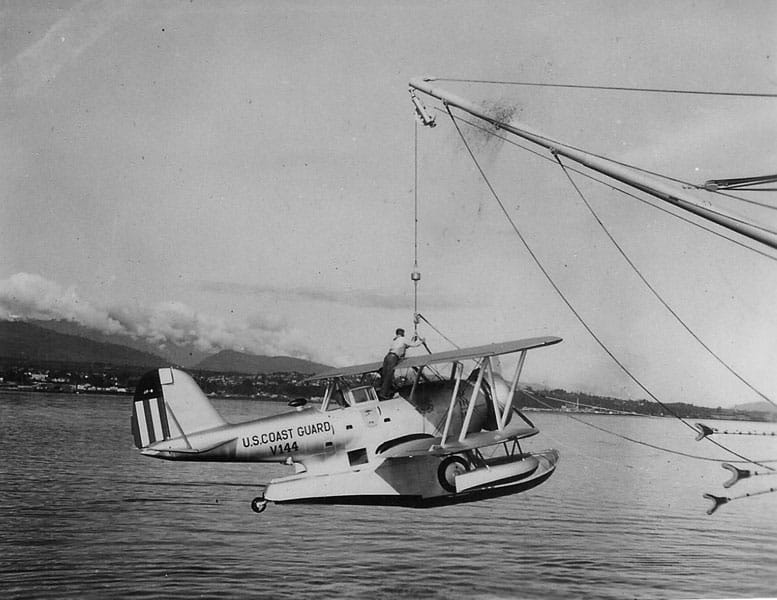

The 327 foot cutters were capable of carrying Grumman J2Fs, Curtiss SOC-4s, and the specially purchased Waco J2W-1s. The aircraft was lifted to and from the cutter by a large boom supported from the aft goal post. Between 1937 and 1941 all of these aircraft operated from the 327s. Usually, an aircraft would be assigned to a cutter for a number of months. Typical of such duty was the Bering Sea Patrol and later the surveying of the Greenland coast.

In 1937 the Coast Guard cutter Spencer was assigned the Bering Sea Patrol and in addition was to be home-ported out of Cordova, Alaska. LT. C. F. Edge had worked with the newly launched 327 foot cutter Campbell to determine maximum sea conditions in which a plane could be launched and recovered. When the evaluation was completed orders were cut to place a JF-2 aboard the cutter Spencer with Edge assigned as the pilot. In addition he was directed to investigate and determine what could be done with Coast Guard aviation in Alaska; what would be needed to do it; and where to establish an aviation operating base.

During the patrol aircraft missions varied; the aircraft transported the ship’s doctor to Kodiak in response to an epidemic of tonsillitis among the kids; it evacuated a badly injured man from a whaling station; there was an acute appendicitis evacuation; and the doctor was flown to many other locations when sick calls from remote areas would came in. The aircraft proved to be especially effective when used with the cutter in searches for overdue trappers and fishermen. The cutter would be a moving base and the aircraft would search the inlets and vast coastlines. In the fall the Spencer sailed for Seattle for supplies and the JF-2 was exchanged for a Waco J2W-1, a four place, single engine bi-plane which could be converted to a seaplane with twin floats. The Waco, evaluated as a patrol aircraft operating from the Spencer, had the advantage of having a four place cabin but was not as rugged as the JF-2 and lacked the JF’s amphibious capabilities. Frank Erickson followed in 1938 on the cutter Hamilton using a JF-2 and continued to illustrate the effectiveness of this aircraft. There were difficulties however. The 327 cutters were originally designed to be equipped with a hangar. This was not to be the case and the weather was rough on the aircraft as it rode in a cradle exposed to snow, ice and salt spray. Even though the control surfaces were secured with padded battens they continuously vibrated in high winds. In protected waters there was little difficulty in putting an aircraft over the side or picking it up but when the ship was anchored in open roadsteads in the Bering Sea there was usually a ground swell causing the ship to roll. This created a problem in keeping the wing tips from hitting the side of the ship as the aircraft was put into or taken out of the water. The last aircraft to operate from a 327 foot cutter was a SOC-4 Seagull on board the Duane when she made a survey of the west coast of Greenland and looked for potential airfield sites.

At the beginning of World War II German weather stations were operating in the Greenland area providing critical data used by the U-Boats. The weather reports had to be stopped and it would require surface vessels to do so. The United States did not own a single icebreaker to assign to duty in the Greenland waters. Ships had to be adapted until new icebreaking gunboats could be built. The closest thing the Coast Guard had to an icebreaker was the cutter Northland designed to serve in Alaskan waters. She was modified to carry an aircraft. Another cutter that saw service in the area, the North Star, available when the Byrd expedition returned in the spring of 1941, was assigned to the Coast Guard. Her cruising endurance and ability to carry an aircraft made her a useful acquisition. A third cutter with aircraft carrying capabilities was the cutter Storis which was built in the early part of the war. Shipboard aircraft could not only find enemy stations and provide search and rescue capabilities but in addition helped the ship pick its way through the ice.

The wind-class Coast Guard icebreakers were designed specifically as aircraft carrying, ice-breaking gunboats for Greenland duty. Initially these vessels were to have catapult capabilities but since these vessels would operate in ice where hostile forces would be encountered it was deemed necessary to have adequate firepower capability. As a result the ships were completed with two twin 5-inch 38 caliber mounts, three quadruple 40 millimeter guns, and six 20 millimeter installations. The ships also were equipped with depth-charge racks and projectors. There was not room for a catapult and a cradle to carry an amphibian was squeezed between the stack and the aft 5-inch mount. Four Wind-class cutters were built for the Coast Guard, three of which were transferred to the Soviet Union.

The Coast Guard’s ultimate aircraft carrying cutter was to have been a 316 foot cutter designed to have a catapult to launch aircraft. This design evolved into the smaller 255 foot Owasco class and the provisions to carry aircraft was eliminated. After the war and the return of the wind-class icebreakers from the soviets the ships participated regularly in Arctic and Antarctic operations with aircraft on board but these aircraft were helicopters developed during the war and much better suited for the operation. Today all deep-water cutters have the capability to carry and operate helicopters.