In the summer of 1917 the United States was fully engaged in World War I and was very concerned about the sinking of Allied ships by German submarines. The Navy was convinced that aircraft had real possibilities as an anti-submarine weapon and developed a steadily improving series of patrol planes capable of flying from the water. There was outstanding improvement in the performance, range, and armament of the flying boat between the beginning of the beginning and the end of the war.

These aircraft proved to be effective but were limited in fuel and depth charge capacity. They also had to be transported to Europe by ship. Ironically, ships carrying the aircraft capable of combating the submarines were being sunk by the submarines. RADM David W. Taylor, the chief of the Navy’s Construction Corps, was convinced that what was needed was a flying boat capable of carrying adequate loads of bombs, depth charges and defensive armament, with a range that would enable it to fly from the United States to Europe. In September of 1917 Taylor formed a team of key men, CDR G.G. Westervelt, CDR Holden C. Richardson, and CDR Jerome C. Hunsaker, and directed them to create such an aircraft. Glenn Curtiss was contacted and within three days Curtiss and his engineers submitted general plans based on two different proposals.

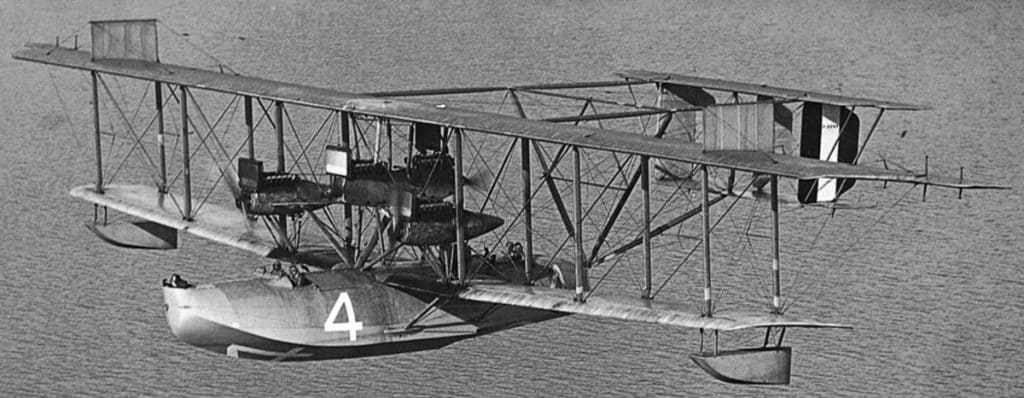

One proposal was for a three engine aircraft, the other a very large five engine aircraft. Both were similar in appearance and differed from conventional seaplanes of the period in that the hulls were much shorter. The large tail assembly supported by hollow wooden booms rooted in the wings and hull was high enough to remain clear of breaking seas during water operations. Many of the design concepts had been embodied in a Curtiss design for a “flying lifeboat” which was the product of the meeting between Glenn Curtiss and CAPT Benjamin Chiswell USCG on board the USCGC Onondaga while moored at the Washington D.C. Navy yard in April of 1916. The criteria for success were a seaworthy hull which would tend to rise out of the water while in motion at high speeds and reliable engines that would provide sufficient power for their weight. Evaluation of weight and load carrying potential and the availability of the light Liberty engine resulted in the selection of a three tractor engine design.

This would later be modified to three tractor engines and one mounted as a pusher which enabled the aircraft to lift off the water with a greater amount of fuel on board.

CDR Richardson was responsible for the hull design. The hull which was 45 feet and 9 inches in length with a 10 foot beam was built of spruce. Lateral stability was provided by small pontoons mounted under the tips of the lower wing. The strength of the hull was proven when the NC-3 was forced to land short of its destination during the Transatlantic Flight and was pounded by heavy seas for two days without sinking. The overall length of the plane was 68 feet 3 inches and the wing span was 126 feet. The aircraft was designated NC, the N was for Navy and the C for Curtiss. The press referred to them as Nancys. was approved. It was decided to assemble the aircraft at the

By December of 1917, design work had progressed to the satisfaction of Secretary of the Navy Daniels and a contract for four flying boats Naval Air Station Rockaway, New York. Captain Stanley V. Parker USCG was the Commanding Officer of the Air Station and his Executive Officer was LT. Eugene Coffin, USCG. CDR John H. Towers USN was the project officer. A special hangar was constructed and the NC-1 assembled by the first of October.

On 4 October CDR Richardson ran a series of taxi tests gradually increasing speed until the aircraft lifted from the water for a few seconds. He then taxied back to the beach and sent word for CAPT Parker to come aboard for the first official flight of the NC aircraft.

The Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918 bringing hostilities to a conclusion. There was no longer a pressing need for a long range anti-submarine airplane. The urgency had gone out of the NC project. While in Europe, CDR Westervelt had learned that several organizations were making preparations for a Trans-Atlantic Flight. In 1913 Lord Northcliffe, the wealthy owner of the London Daily Mail, offered a prize of 10,000pounds ($50,000) for the first successful Trans-Atlantic flight. With the outbreak of World War I the offer was cancelled but renewed after the war. Upon his return to Washington Westervelt wrote a 5000 word report expressing the need to participate with government backing which would result in a considerable amount of deserved prestige. The report outlined proposed routes and procedures. Secretary of the Navy Daniels approved the basic plan and work at the Rockaway Air Station resumed a feverish pace.

There had been a change in Lord Northclffe’s rules when the prize was reinstated. Mid–ocean stoppages would no longer be allowed thus effectively eliminating the NC’s. It made little difference as the United States had made no attempt to file an entry fee and the Navy crews would not have been able to accept any possible prize money that might have been awarded. The attempt had become one of accomplishment and pride on the part of the Navy. Credence was lent to this announced policy when in an unprecedented ceremony the flying boats were placed in commission as if they were ships of the line. CDR John Towers formally assumed command of NC Seaplane Division One. His orders signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt, acting Secretary of the Navy, gave Towers a status roughly equivalent to that of a destroyer flotilla’s commander. The Navy had committed to go all out. A Trans-Atlantic departure date of 6 May was chosen. While the flying boats were being readied for the flight the NC-2 was damaged in an accident during take-off during evaluation testing. On the night of 4 May a fire damaged the NC-1 and NC-4. Parts from the NC-2 were used to repair the NC-1 and NC-4 in an around the clock effort leaving only three aircraft for the attempt.

Towers chose NC-3 as his “flagship” and chose CDR H.C. Richardson as his first pilot with LT David McCulloch as his co-pilot. LCDR P.N.L. Bellinger was in command of NC-1 with LCDR Marc Mitscher assigned as first pilot and LT Louis T. Barin as co-pilot. NC-4 was commanded by LCDR Albert C. Read with LT. Elmer Stone USCG as first pilot and LT(jg) W. K. Hinton as co-pilot. Other crewmembers of NC-4 were Ensign H.C. Rodd, radio operator; Lt. James Breeze, engineer: and Chief Machinists Mate E.C. Rhoads, relief engineer. The Aircraft Commanders were navigators and operated from the bow of the aircraft. In addition to standard navigational gear they were equipped with the new “bubble sextant” and a drift indicator

Dr. (CDR) Hunsaker in his memoirs states:

“The big boats had dual controls and the two aviators sat side by side and worked together on the controls which required strong effort at times. Read was a relatively small man, and he chose Stone because of his size and strength. The two were a good team. Stone had experience with flying boats, which were notoriously difficult to keep from stalling in rough air or at reduced speed. Stone also had experience in bad visibility weather. Stone had been a test pilot and knew how the crude instruments of the day could give indications contrary to the reliable “seat of the pants” signals of acceleration. On the eighteen hour flight of the NC-4 to the Azores, Reed’s function as a navigator required him to stand in the forward cockpit. Stone was in fact the chief aviator with Lt Walter Hinton sitting beside him as a partner.”

The planned route of flight would take the aircraft over Cape Cod to Halifax, Nova Scotia and then from there to Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland. The next leg would be 1300 miles to the Azores and then to Lisbon Portugal. After crossing the Atlantic, the NC-4 flew on to Plymouth, England. The support was massive. Five battleships served as weather stations and destroyers were place at 50 mile intervals along the open ocean track on the planned route. The Destroyers were equipped with special radio direction finders and star shells to be fired as the planes passed overhead.

Time was of the essence. There were others preparing to make the flight across the Atlantic. There had been no departure date given the press so there was little fanfare as the three NC flying boats lifted off at 10:00 am on the 8th of May. The NC-4 had flown only once prior to the departure and the leg to Halifax was to serve as the “shakedown’ flight. After passing Cape Cod and over the open sea the NC-4 had to shut down the center pusher engine due to an oil leak. LCDR Read realized this would slow him but elected to continue on as the aircraft would fly well on three engines. At 2:05 pm they passed over the first “station,” the destroyer McDermut, on course. They were headed for the next destroyer when the center tractor engine blew a rod. A distress signal was sent out which both destroyers heard. Towers assumed the aircraft would land next to the McDermut for repairs and continued on. Course was altered but the aircraft was losing altitude in poor visibility and with the water calm enough for a safe landing Read directed the NC-4 be turned into the wind and a landing made. Once on the water they could not get through on the radio. Finding themselves in the open sea, 80 miles from the nearest land they commenced a taxi for Chatham Air Station. At dawn, just off the beach, they were spotted by two search aircraft. Within two days the bad engine was replaced and the other repaired. The only engine available at Chatam was a 300hp liberty but it had to do until the NC-4 reach Trepassey Bay where a 400hp engine was available. Departure from Chatam was delayed until the 14th because of a 40 knot northeaster.

The NC-1 and NC-3 ran into heavy weather enroute. Buffeted by gusty winds it took the effort of both pilots to remain on course. They arrived at Halifax that day but propeller problems delayed their departure until the 10th. They followed the line of “station” ships and as they passed Placenta Bay they sighted their first icebergs. The air remained rough and it was now cold. At Trepassey Bay strong swells were running and the landings were made in strong gusty winds and an “avalanche of spray.” By evening both NCs were safely moored near the base ship USS Aroostook. Weather was still delaying the British attempt from St.Johns and the press was once again focused on the big flying boats.

The NC-4 did not depart Chatam Air Station until the afternoon of the 14th which would have put them into Trepassey Bay after dark. Read decided to land at Halifax rather than to risk the night landing. The center engine vibrated badly on the flight and the two outboards were running rough with dirt in the carburetors. Breese and Rhoads worked on them and the NC-4 was back in the air at 1253 on the 15th bound for Trepassey Bay. Shortly after takeoff a message was received that the NC-1 and NC-3 would take off that afternoon. As the NC-4 rounded Powell’s Point they saw that the NC-1 and NC-3 had not departed yet. They had been trying to take-off for a period of time but neither aircraft would lift from the water. Breese on the NC-4 knew what the problem was. The NC fuel gages had been calibrated with the aircraft on land. The aircraft had been moored in the harbor. On the water the aircraft rode slightly nose down so when a tank was filled to the full mark they held a little over 200 pounds of additional fuel. The weight critical NC-1 and NC-3 were too heavy for takeoff. Departure was rescheduled for the following evening so that the aircraft would be approaching the Azores during daylight. This gave the crew of the NC-4 time to change the center engine and test it in time for departure.

On the evening of the 16th the three NCs taxied out together and headed down the Bay in a formation take off. The NC-4 lifted off but the other two did not. They signaled for the Aroostook’s small boat to come alongside they began removing weight. The NC-4 had returned and landed. All three again took up positions as far back in the harbor as possible and at 1800 they started once again. Bouncing across the crests they took to the air, the NC-4 most easily of all. The route between Trepassey Bay and Ponta Delgada in the Azores was marked by a string of 25 “station” destroyers at approximately 50 mile intervals. The radio direction finders worked poorly but each destroyer was to make smoke, or if at night, swing a searchlight from the surface to straight up. Star shells were fired and a report by radio of the passing of the aircraft was made and the next destroyer alerted. Formation was maintained until dark when Towers ordered running lights be turned on. The lights on the NC-4 came on but not on the other two aircraft. Realizing this he ordered the formation opened up to reduce the danger of collision. Weather remained good through the night but with the morning came rain, thick low clouds and fog.

Towers spied a ship through a hole in the clouds. In the fog he mistook it for one of the “Station” destroyers. It was in fact the Cruiser Marblehead returning from Europe. Based on the sighting, Towers changed course. This was a costly mistake. The NC-3 ran into heavy rain squalls and tried different altitudes all to no avail. The clouds were so thick they could not see their wing tips. Turbulent air would shake the wallowing aircraft and with the primitive instruments of the time it was difficult to determine the attitude of the airplane. By 11:30 Towers figured he must be in the vicinity of the islands but he also knew he was off course. With two hours of fuel remaining and the very real possibility of running into a mountain on one of the islands he decided it would be better to set the aircraft down on the water and wait for the weather to moderate. A descent was made and passing through 500 feet they could make out the surface of the ocean. It did not look too bad so he signaled Richardson to make the landing. They mis-read the swells hitting the first one hard, fell into the hollow, shot back into the air and smashed into the following wave. Struts on the center engine buckled, hull frames split and damage was done to the controls. It was apparent that flight could not be resumed. Communication attempts were futile. The aircraft drifted with the nose down into the wind which set it on a course to Ponta Delgada. Two days later the aircraft was in sight of the breakwater. Towers had the two outboard engines started. They vibrated badly but provided enough power to taxi into the harbor and up to a mooring buoy.

Bellinger in the NC-1 made the same decision as Towers. The aircraft had been flying at 75 feet altitude. Navigation was impossible and down that low they could not reach anyone on the radio. Mitscher was flying the plane and was ordered to land. When the NC-1 touched down it was buried in a large wave which broke the wing struts and tail beams. The wings began to fill with water and it was necessary to slash the fabric. The hull had been damaged and was taking on water requiring constant bailing. About three hours after water entry they were spotted by the Greek Steamer IONIA and picked up. A short time later they were transferred to the USS Gridley. An attempt was made to take the aircraft in tow but it was so badly damaged that it was decided to sink it.

The NC-4 was also in weather. As the weather continued to deteriorate Read motioned to Stone to take it up and the NC-4 broke out on top at 3200 feet. As they approached the position of the next destroyer Read gave orders to descend for a visual check. As they entered back into the clouds the aircraft began to buffet and became difficult to fly as was the norm. A wing dropped and the aircraft went into a spin. Apparently no one realized it until a glimpse of the sun was caught through a break in the clouds. Read shouted for Stone to bring it out of the spin. This he did. To bring such a large heavily loaded aircraft out of a spin in clear weather would have been an accomplishment but the NC-4 had reentered solid clouds with zero visibility and to be able to bring it out of a spin with the rudimentary flight instruments then available was an amazing feat. Once Stone had the aircraft under control he again climbed above the clouds. Read elected to stay there and use dead reckoning for the islands. In mid morning the NC-4 passed over an opening in the clouds. Read saw what he thought was a riptide. Examining the two shades of color below, he realized that the darker mass was land. Read directed Stone to spiral down to 200 feet. Using time and distance and visual reference they determined they were at the southern tip of Flores, one of the western Azores. Read set a course for Ponta Delgada 250 miles away. They passed over a “Station” destroyer shortly thereafter but it was not long before the weather began to deteriorate again. The fuel was too low to facilitate searching in case they missed Delgada so Read decided to turn south for Horta on the Island of Fayal where the USS COLOMBIA was standing by. They landed in harbor at Horta at 1323. A tremendous welcome awaited Read and his crew.

For almost three days NC-4 rode her moorings at Horta, kept there by rain squalls and fog. On the 20th the weather cleared enough for takeoff, and in less than two hours the NC-4 reached Ponta Delgada. They were met by the governor, the mayor and a multitude of people. Towers and the crew of the NC-3 and Bellinger and crew of the NC-1 were there to greet them. It would be 30 May before the weather was good enough to continue on to Lisbon. While at Ponta Delgada word came that the Britishers Hawker and Grieves had taken off from Newfoundland for Ireland on the 18th and had been picked up by a steamer after being forced down 1100 miles east of St. Johns. Alcock and Brown were standing by for takeoff as soon as the weather cleared.

On Tuesday May 27th, the crew of the NC-4 was up before dawn. The engines and radio was checked out and on the signal from Read, Elmer Stone advanced the throttles and the big flying boat lifted off in the early morning for Lisbon Portugal. Another chain of destroyers extended between the Azores and Lisbon. The weather was good and as the NC-4 passed over each destroyer the ship radioed a message of her passage to the base ship Melville at Ponta Delagada and the cruiser Rochester in Lisbon who in turn reported to the Navy Department in Washington. At 19:30 the flashing light from the Coba da Roca lighthouse was spotted and the NC-4 passed over the coast line. The big aircraft turned southward toward the Tagus estuary and Lisbon. At 20:01 on May 27, 1919, the NC-4s keel sliced into the waters of the Tagus. The welcome was tumultuous. A transatlantic flight, the first one in the history of the world, was an accomplished fact!

Early in the morning of 30 May the NC-4 departed Lisbon for Plymouth England. The NC-4 sat down in the Mondego River to investigate an overheating engine. The radiator had developed a leak and was repaired but because of a low tide condition it became too late in the day to take off and reach Plymouth before dark so Read proceeded to Ferrol in northern Spain to spend the night. They were back in the air the next morning and as they approached Plymouth a formation of Royal Air Force seaplanes escorted the NC-4 into the harbor. A British warship fired a 21 gun salute as the NC-4 circled. The Lord Mayor of Plymouth received CDR Read and his crew and from Plymouth they went to London where they were decorated by the King of England. President Wilson, who was at the Peace Conference in Paris, sent for them, congratulated them for their outstanding achievement and introduced them to all present.

Lt. Stone was honored for his part in the NC-4 flight by the Portuguese Government with the award of the Tower and the Sword; by the British Government with the British Air Force Cross; and by the United States Government with the Navy Cross. He also received the following citation from the Acting Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, dated 23 August 1919.

“ I wish to heartily commend you for your work as pilot of the Seaplane NC-4 during the recent Trans-Atlantic flight expedition. The energy, efficiency, and courage shown by you contributed to the accomplishment of the first Trans-Atlantic flight, which feat has brought honor to the American Navy and the entire American Nation.”

On 23 May, 1930, President Herbert Hoover presented Stone and the other members of the NC-4 crew with gold medals, especially designed to commemorate the NC-4 flight, in the name of the United States Congress

The NC-4 returned from Europe and was put on display in New York’s Central Park, and in several other locations, including Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. The NC-4 was obtained by the Smithsonian Institution in 1920. Only the hull was exhibited due to the lack of facilities to display the aircraft in its entirety. The Smithsonian decided to fully restore the NC-4 for the 50th anniversary of the first transatlantic crossing. With the assistance of three Navy technicians, the restoration of the NC-4 was completed and the aircraft was displayed on the national Mall for the 50th anniversary celebration on May 8, 1969. After the brief exhibition, the NC-4 was disassembled and placed in storage until it was loaned to the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida, in 1974. It is a feature display at the Naval Aviation Museum.

A Chronology of Accomplishments

Commander Elmer F. Stone

United States Coast GuardElmer F. Stone graduated from the Revenue Cutter School of Instruction on June 7,1913, completing an engineering curriculum and receiving a commission as a Third Lieutenant U.S. Revenue Cutter Service. During his career, Stone, a visionary, accomplished a great deal. He served his country selflessly for over twenty-five years. He was the first Coast Guard Aviator and the pilot of the first aircraft to successfully fly across the Atlantic Ocean. He had a profound effect on the successful development of Naval Aviation. During the first nine years after graduating from Naval Flight Training he spent all but a little over a year assigned to the US Navy at the Navy’s request. A Chronology of Stones contributions and achievements follow.

January 28, 1915

The Coast Guard was formed from the merger of the Revenue Cutter Service and the U.S. Life-Saving Service. The ranks of Cutter service Officers were retained until 5 June 1920, when the military ranks prescribed for the Navy became effective for the Coast Guard.

March 21, 1916

The Commandant issued orders for Third LT Stone to test an air search operational concept for distressed vessels, obstructions to navigation, and for law enforcement. Glenn Curtiss supported the test and loaned a Curtiss MF Flying boat. The concept was proven. Stone requested Naval Flight training and his request was approved.

April 10, 1917

Third LT Stone completed Navy flight school. Designated Coast Guard Aviator number 1 and Naval Aviator number 38. The United States had entered WWI and the Coast Guard had been transferred to the Navy Department on April 7.

July 2 1917

Third LT Stone was assigned to the armored cruiser USS Huntington as a Curtiss R-6 aircraft pilot. The catapult system was less than satisfactory and Stone would provide a solution at a later date.

October 13, 1917

Third LT Stone was ordered to temporary command NAS Rockaway until the arrival of a regularly designated Commanding Officer at which time Stone would become the Seaplane Officer. For the next eight months. Stone flew seaplanes and amphibians. NAS Rockaway was an important facility for naval aviation’s seaplane development and growth and Stones abilities did not go unnoticed.