The Coast Guard Aviators Served With the Air Force Combat Air Rescue and Recovery Squadrons in Vietnam

The Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered that search and rescue forces be sent into Southeast Asia in May of 1964. The primary responsibility was given to the U.S. Air Force.

When the first units of the Air Rescue Service arrived with the short range HH-43B helicopters they were not prepared for the unique challenges of combat aircrew recovery in the jungles and mountains of Vietnam and Laos. This deficiency was directly attributable to the draw-down of forces which took place in the late 1950’s. The concept, during this period was one of massive nuclear retaliation. Consequently the Air Force committed itself to a peacetime Search and Rescue capability. Helicopters were assigned to individual Air Force bases based on a study that determined that almost all accidents occurred within a 75-mile radius of the base of operations. Each base had a local base rescue detachment consisting of two or sometimes three helicopters. By the end of 1960, the Air Rescue Service (ARS) consisted of three squadrons and 1,450 personnel.

The Air Rescue Service struggled to catch up. In June of 1965, four-engine WW II-era transport HC-54s assumed interim duties as the rescue control aircraft. They were later replaced by HC-130’s. In August 1965, A-1 Skyraiders began escorting rescue helicopters. In October the first of the HH-3E helicopters arrived. These aircraft had a good rescue hoist, drop tanks that increased the range, armament, and the more powerful T-58-5 engine. Of significant importance, was the titanium armor added to the HH-3E to protect the crew and critical helicopter components.

On 8 January 1966 the Air Rescue Service became the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service (ARRS), and the 3rd Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Group (ARRG) took charge of all rescue operations in the Vietnam geographical area. Improved tactics were instituted and better equipment came into being. In-flight refueling of the HH-3Es, utilizing HC-130Ps as refuelers, became operational in June of 1967. However, due to the demonstrated ambivalence toward the helicopter, the Air Force requirement for the HH-3E had not been scheduled into the production line. As a result, the needed number of aircraft was not obtained until the first quarter of 1968. The HU-16s, replaced by the HH-3Es, were phased out during the fall of 1967.

Things improved but the rapid increase in rescue requirements generated by direct involvement of US forces created an acute shortage of experienced HU-16 and helicopter pilots. The Air Force approached the Coast Guard for supplemental help at the beginning of 1966. An aviator reciprocal exchange program was suggested. It was not until March 1967 that the Coast Guard signed off on an implementing Memorandum of Agreement.

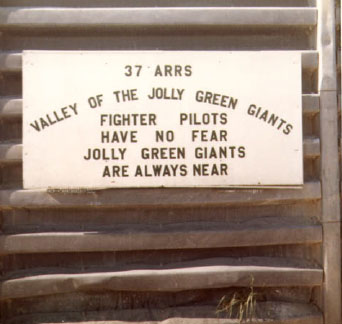

Orders were cut for the initial group of Coast Guard aviators under the Coast Guard – Air Force Aviator Exchange Program in July of 1967. From the eighty plus volunteers two fixed wing and three helicopter aviators were selected. The fixed wing aviators, both HU-16E qualified, were LT Thomas F. Frischmann and LT James Casey Quinn. Because the HU-16E was being phased out, both pilots received orders to attend the Advanced Flying Course for the C-130 aircraft. This completed, they received orders to report to the 31st ARRS, Clark AFB, Republic of the Philippines. LT Frischmann remained there. LT Quinn transferred to the 39th ARRS at Tuy Hoa, South Vietnam. The helicopter pilots selected were LCDR Lonnie L. Mixon, LT Lance A. Eagan, and LT Jack C. Rittichier. They were transitioned to the HH-3E helicopter and assigned to the 37th ARRS at DaNang for combat rescue duty arriving on April 3, 1968 In preparing for this assignment they attended the Air Force Survival School at Fairchild AFB, Washington. This was followed by training in the HH-3E twin engine amphibious helicopter at Sheppard AFB, Texas. They then received advanced combat crew training in January at Eglin AFB, Florida. This was followed by high altitude helicopter flying in the mountains near Francis Warren AFB, Wyoming and jungle survival training at Clark AFB in the Philippines. They arrived in DaNang on April 3, 1968. LT Richard V. Butchka, LT James M. Loomis, and LTJG Robert T. Ritchie followed in April 1969. LCDR Joseph L. Crowe, and LT Roderick Martin III arrived in 1971 and LT Jack K. Stice, and LT Robert E. Long followed in 1972. All of these aviators were helicopter qualified and were assigned to the 37th ARRS at DaNang.

The Air Rescue Forces, known as the Jolly Green Giants, consisted of only two squadrons. The 40th was initially at Udorn Thailand and later moved to NKP. The 37th was at DaNang. The 37th ARRS initially had 14 HH-3Es assigned. The squadron was authorized 21 each pilots and copilots but rarely would have more than 70 to 80 percent of that number on board. Only 25 percent of replacement pilots were qualified as Aircraft Commander. Experienced helicopter pilots, especially those with over water experience, had been a problem since shortly after initial deployment. The situation was further impacted with the formation of the 20th Helicopter Squadron activated in October 1965 and the 21st Helicopter Squadron formed in 1967. These squadrons, part of the 14th Air Commando Wing, operated out of NKP and performed counter insurgency missions and mission support in the CIA war in Laos. This “Top Secret” operation, called Pony Express, further depleted the supply of experienced helicopter pilots available to the ARRS. ARRS requirements were met by transitioning fixed-wing pilots to helicopter operations. These pilots arrived in Southeast Asia directly from initial helicopter training.

The Coast Guard aviators, well experienced helicopter pilots, arrived fully qualified. Though often junior in rank, the Coast Guard pilots found themselves flying with a Major or Lieutenant Colonel as a copilot, but the rank disparity never interfered with the mission. Additionally, because of their experience, they were designated Instructor Pilots and were used extensively to train newly arriving pilots. LCDR Mixon was cited for developing new improved water recovery tactics and medical evacuations from surface vessels. Shipboard operations were and would remain a Coastie operation. Lieutenant Colonel Charles R. Klinkert, USAF, the 37th ARRS Commander in October 1968 said “The Coast Guard Aviators have been a terrific assist to the Air Force. Very few of us had any experience in this helicopter. These gentlemen came in here and helped us become real effective in this type of mission. I can’t say enough about them.” There were a series of commendations from the Air Force to the Commandant of the Coast Guard praising these men not only for their aeronautical skill but also the courage and valor they displayed in combat.

The Coast Guard aviators, well experienced helicopter pilots, arrived fully qualified. Though often junior in rank, the Coast Guard pilots found themselves flying with a Major or Lieutenant Colonel as a copilot, but the rank disparity never interfered with the mission. Additionally, because of their experience, they were designated Instructor Pilots and were used extensively to train newly arriving pilots. LCDR Mixon was cited for developing new improved water recovery tactics and medical evacuations from surface vessels. Shipboard operations were and would remain a Coastie operation. Lieutenant Colonel Charles R. Klinkert, USAF, the 37th ARRS Commander in October 1968 said “The Coast Guard Aviators have been a terrific assist to the Air Force. Very few of us had any experience in this helicopter. These gentlemen came in here and helped us become real effective in this type of mission. I can’t say enough about them.” There were a series of commendations from the Air Force to the Commandant of the Coast Guard praising these men not only for their aeronautical skill but also the courage and valor they displayed in combat.

Col. Klinkert’s statement as to effectiveness was correct. The Jolly Greens became the best at what they did. A number started with little experience but of necessity they learned fast and they learned well. No one can question their courage and dedication to the mission. A number of the pilots flew on second and third combat tours and the enlisted crews were almost all multi-tour vets by 1972. Col. Frank Buzze who flew F-100s in the war wrote the following; “They were called Jolly Greens with near reverence by US combat pilots. Jet pilots are a pretty individualistic lot, and will argue about almost anything but a sure way to start something is for someone to bad-mouth the Jollys. No one did.” The Coast Guard aviators were fiercely proud to be part of the Jolly Greens. The Air Force treated them as their own. They were called “Coasties.” The term was one of respect. Major General Don Shepard, a Misty pilot during the war stated that the Jollys were the bravest of the brave.

Where did these men get the courage to go out almost daily for a year knowing that hostile forces were waiting to kill them each time they went? Mixon did not know, other than to observe that some found strength in religion; some found it in drink; and others in themselves. Only those who have willfully place themselves in harm’s way and experience the deep innermost feelings which come from saving another’s life can truly understand. Fear was present – it did not go away, but a brave man can control it and even use it to his advantage. Without fear there is no courage. Butchka said each time he got ready to go his mouth felt dry and he found speaking was an effort, but once into the mission, this would disappear. The Jolly Greens were determined to make the save. The “Bad Guys” were determined not to let it happen.

The Air Rescue forces in Southeast Asia didn’t get all of the downed airmen but no one can say they didn’t try. They did get 3,883 and provided the world with thousands of examples of unselfish humanity. A report prepared by the Air Force Inspection and Safety Center, summarizing helicopter use in combat rescues, noted that during the Vietnam War, between 1965 and 1972, helicopters came under significant hostile fire in 645 opposed combat rescue operations involving downed aircraft. Crews were rescued in six hundred, or 93 percent, of these cases. This was not accomplished without cost. The 37Th ARRS lost 28 men including Lt. Jack C. Rittichier USCG.

The Coast Guard aviators who served on the rescue team were highly praised by many. They stated that their exceptional proficiency was a product of their motivation to save lives, rather than individual brilliance. They no doubt downplayed themselves to avoid sounding boastful, but the commendations and awards presented to them proved not only their incentive, but most certainly their flying skills and bravery as well. This group of men were awarded 4 Silver Stars, 15 DFC’s, and 86 Air Medals

Their numbers were not large — Their contribution was. They were all volunteers who regularly put their lives on the line to save fellow airmen who were in peril of death or capture. The focus was on duty, honor, country, and Coast Guard. Their mission was noble. Their performance brought honor upon themselves, Coast Guard Aviation and the United States Coast Guard. History should ever reflect their honorable actions.

Note: The complete story, titled “Coast Guard Aviation in Vietnam – Combat Rescue and Recovery’, detailing the exploits of these men, is available from the Ancient Order of the Pterodactyls.