As a result of the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Germany was bound by agreement to declare war on the United States. The United States and Germany declared war on each other on December 11, 1941. Unlike most navies operating submarines the primary target of German U-boats was merchant shipping in order to cripple the enemies’ ability to wage war. Admiral Karl Donitz, the Commander of German Submarine Forces, immediately drew up plans for operation Paukenschlag (“Drumbeat”), a devastating attack on shipping along the North American eastern seaboard, arguably the most congested sea-lanes in the world, using 12 of the longer range Type IX boats. Donitz believed that the industrial cities of the eastern seaboard were vulnerable to the disruption of these sea-lanes. Oil was critical for the American war effort. Most of the oil was provided by ships carrying it from the Netherlands West Indies, Venezuela, and the Gulf of Mexico ports of Houston and Port Arthur Texas. The Naval Staff in Berlin, however, would release only six U-boats, one of which encountered mechanical difficulties, leaving only five submarines for the opening moves of the campaign.

As the U-boats exited the Bay of Biscay they were picked up and plotted by British intelligence. The progress of the submarines was observed and it was deduced that the target area was the North American eastern seaboard. This information was passed to Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, but little or nothing was done about it. There was a shortage of anti-submarine vessels partly because of President Roosevelt’s 1941 decision to loan 50 obsolete destroyers and Coast Guard Cutters to Britain in exchange for bases and partly because available escorts were used for North Atlantic convoy duty. ADM King directed a frantic effort to reinforce the Pacific Fleet and compensate for losses. VP-51, VP-71, and VP-72 were ordered to the West Coast and thence to Hawaii. Patrol Wing 8 was transferred to the West Coast. VP-52 and half of VP-81 stationed at Key West were immediately sent to patrol the Pacific approaches to the Panama Canal in case of a Japanese attack. To compound the problem ADM King held the Atlantic Fleet in reserve. For all practical purposes the East Coast of the United States had been stripped of escort vessels and its anti-submarine aviation.

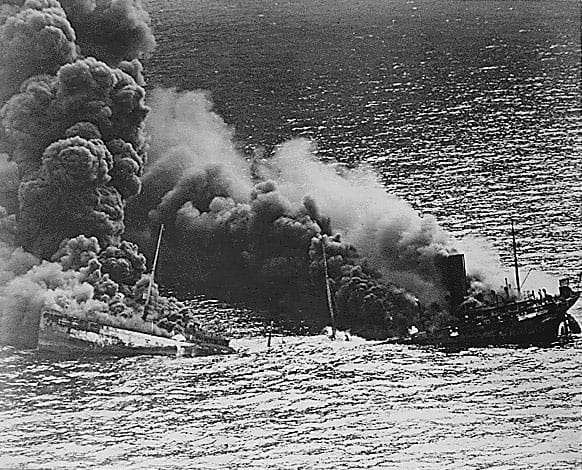

The German offensive began 11 January 1942 when U-123 sank the SS Cyclops south of Nova Scotia. The first wave ended operation on February 6 and headed back to Germany. They sank 25 ships for a total of 156,939 tons. They were replaced by succeeding waves of U-boats without interruption. During the first six months of the U-boat offensive in North American coastal waters 397 ships totaling over 2 million tons were sunk with the loss of roughly 5000 lives. In the process only 7 U-boats were sunk.

Rear Admiral Adolphus Andrews, Commander of the Third Naval District was given the command of the North Atlantic Coastal Frontier consisting of the First,

Third, Fourth and Fifth Naval Districts. This would later expand southward and become the Eastern Sea Frontier. At the beginning of January the surface craft available to him to combat the U-boats were 4 – PY boats, 4 – SC boats, 1 – 165 ft Coast Guard Cutter, 6 – 125 ft Coast Guard Cutters, 2 – PG boats, and 3 – Eagle Boats. The review of the aircraft revealed similar conditions. There were 51 – Trainers, 18 – Scouts (OS or OB) 14 – Utility, 7 – Transport, and 6 – Patrol aircraft. Of this number 18 were Coast Guard aircraft; all of them unarmed at this time.

Once in the hunting grounds, German submarines would rest on the continental shelf from early morning until late afternoon. During the day the U-boat would rise to the surface for air and sunlight, usually during late morning for a limited time, submerging again if sighting any object. Late in the afternoon they began the night’s activity against the shipping lanes. Unbelievably the merchant ships ran with their running lights on and were silhouetted against the fully-lit coastal cities and resort towns. All navigation aids were still lit and the ships followed the established sea-lanes. The surfaced submarine would lay in wait for an appropriate target to pass by. Surface attacks were preferred by the U-boat commanders. The Type IX boat had a surface speed of 18 knots. The submerged range was limited to 70 miles at 4 Knots. Periscope depth attacks were made if operations dictated. With the advent of submarine tankers the VII boat also began operating in American waters.

An aerial patrol utilizing available aircraft was initiated. With the limited daylight operations conducted by the submarines and the effectiveness of aircraft limited by a lack of radar and darkness, the odds of locating a submarine were not good. What they did see were oil slicks where the tankers had been sunk, debris, lifeboats with survivors, people clinging to rafts, some in life jackets and dead bodies. This was the result of the previous night’s U-boat activity. The aircraft would drop provisions to provide immediate help, find a ship or boat and direct it to the survivors. Many were wounded or badly burned and in great need of medical assistance. Others were beyond the point of endurance and slipped away into the sea. When evaluating the situation the lives of the survivors were balanced against the risks off an offshore landing. Many landings were made. Coast Guard records showed 95 landings in the sea and over 1000 rescued during the period Jan 1942-June 1943.

Three OS2U Kingfishers on a routine patrol spotted men in the water 30 miles east of Cape Hatteras. Depth charges were dropped in an area where it would not injure the men. All three aircraft landed and picked up all the survivors who rested on the wings until a boat arrived from the Elizabeth City air station to pick them up. A PH-2 Hall boat, while on patrol, spotted a large oil slick 100 miles south of Biloxi, Mississippi. This marked the spot where a German U-boat had torpedoed and sunk a Norwegian oil tanker which had been traveling unescorted. Two badly damaged lifeboats and several survivors were spotted in the rough oil covered sea. With no sign of a U-boat in the area the PH-2 landed and taxied close to the damaged lifeboats. The aircrew removed one sailor with an apparent broken back. Several others suffering from severe burns were taken aboard as the life boat broke apart and sank. The crew taxied the aircraft through the thick oil rescuing a total of twenty-one sailors from the sea. An OS2U Kingfisher on patrol out of Miami received a radio message to search for survivors of the torpedoed tanker GULFSTATE. When locating the remains of the tanker the pilot saw three groups of survivors. Dropping the depth charges in a location distant from those in the water he landed and picked up the three men in the first group. He taxied to the second group and gave them his rubber raft for support and proceeded to the third group, one of which was badly burned, and took them aboard his already overloaded aircraft. He then stood by until additional aircraft arrived to assist.

A favorite hunting ground for German submarines was in the waters off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. The narrowness of the continental shelf enabled the U-boats

to operate in deep water close inshore with great effectiveness. Ordinarily two U-boats were stationed there operating on a carefully prepared schedule. On the 25th of January three J2F-5s were taken from the Atlantic Fleet pool, configured to carry two 325 pound depth charges and stationed at the Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City. Elizabeth City was chosen because of its strategic location. Two days later Aviation Pilot Harry Logan made an attack on a submerging submarine straddling it with two 325 pound depth charges. On 28 January RADM Andrews attempted to obtain additional aircraft for the CG air station. He wrote to ADM King “It is understood, there are approximately twenty PBY-5s belonging to the Royal Air Force now at Elizabeth City, N.C. and due to lack of ferry crews they are not in transit. In view of the immediate demand for long range patrol planes – it is suggested that arrangements might possibly be made for temporary assignment for six of the PBYs at Elizabeth City until such time as suitable replacements can be furnished.”

The request was not approved. However, by means of local arrangement, two PBY-5As were made available for a short duration.

Commander, North Atlantic Naval Coastal Frontier in a memorandum written at the end of the month on conditions in the Fifth Naval District stated

“The available forces have been entirely inadequate to handle the situation properly. Constant offshore patrols should be kept off the Capes and the critical Hatteras area. This is impossible with the forces available.”

It was pointed out that from the 18th to the 25th, when there were no armed planes at Elizabeth City, six sinkings occurred within a radius of fifty miles of Cape Hatteras. On that day three armed J2F-5s began a patrol from Elizabeth City with the center of the assigned area the Diamond Shoal Light Vessel buoy. In the remaining six days of the month not one vessel was sunk in the area. RADM Andrews recommended to ADM King that armed naval aircraft for long range patrol be assigned to the Coast Guard Air Stations in the Frontier, in lieu of the unarmed obsolete equipment now being used for offshore patrol. He emphasized that the Coast Guard pilots in question had Navy training and were exceptionally competent to carry out Frontier offshore patrol. There is a certain irony in the fact that the patrol planes at Norfolk could perform only limited service because they were being used to train pilots while the contribution of the experienced pilots of the Coast Guard was restricted because of the “unarmed obsolete” planes used.

In February negotiations were begun which promised to alter this situation. On the last day of January, the Commandant of the Coast Guard informed the Bureau of Aeronautics that personnel under his command were not being used to full advantage. It was his recommendation that forty-six additional planes be assigned to bases throughout the country. One week later the Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics approved this recommendation with the suggestion that forty OS2U-3s be assigned to Coast Guard Stations as soon as possible. On the ninth of the month, the Chief of Naval Operations took further action in the matter by ordering that all of these aircraft be located on the Eastern Coast instead of dispersed throughout the country as originally planned. On the 13th, the planes were assigned to five Coast Guard air stations from Salem, Mass., to St. Petersburg, Florida, but the dates of delivery were estimated as February 27 through March 11. The first OS2U-3 was delivered on the 28th and the rest at the rate of four per day. Additional OS2U-3s were later delivered to the Biloxi and San Francisco air stations. The JRFs and the increasing numbers of J4Fs were fitted with bomb/depth charge racks and in some cases local fabrications provided additional capability to previously unarmed search planes. The Coast Guard air stations finally had armed aircraft.

By the end of 1941 the British Navy had developed convoy protection to the point where Admiral Doenitz elected to deploy assets to the mid-Atlantic. It was suggested to Admiral King that a similar convoy system be set up to combat the German submarine operations along the eastern seaboard of the United States. ADM King rejected the suggestion. In March representatives of the petroleum industry met with the Navy and War departments warning them that if the rate of tanker sinkings was maintained that America would be crippled due to the lack of oil. The situation was so serious that in the same month Winston Churchill wrote President Roosevelt “I am most deeply concerned west of the fortieth meridian and in the Caribbean Sea. The situation is so serious that drastic action of some kind is necessary.” President Roosevelt got ADM King’s attention and RADM Andrews was directed to plan and develop a coastal convoy system. RADM Andrews put a temporary convoy system, referred to as the “Bucket Brigade,” into operation which moved ships from protected anchorage to protected anchorage by whatever escort vessels were available.

During January and February the preponderance of sinkings occurred along the coastline between Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to a point south of Cape Cod, Massachusetts and then off shore on the route to Halifax, Nova Scotia where Atlantic convoys were formed. By April the majority of all sinkings were occurring in the Cape Hatteras area. Based on this information the Commander Eastern Sea Frontier chose the Cape Hatteras area to evaluate the effectiveness of the convoy system. RADM Andrews’s assets were still limited but more were coming available. Ships sailing between the Chesapeake and Cape Lookout spent the night in protected anchorages. In the early morning the merchantmen would form up in four ship columns. RADM Andrews had Two Coast Guard 165 foot cutters, Four Coast Guard 125 footers, eight British trawlers, four PC-110 footers and a pool of 20 Coast Guard 83 footers attached to the Fifth Naval District that were available. Aircover was provided. Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City had the patrol responsibility for the Cape Hatteras area.

The activity report of the Eastern Sea Frontier lists an attack on an enemy submarine by a Coast Guard OS2U on 7 April, another on 8 May, and on May 15 an OS2U spotted a U-boat off Cape Hatteras. Twelve men were seen on deck just as the aircraft started the bombing run. The U-boat at the same moment began to dive. Ten of the submariners were able to get down the hatch but two were left on deck. Two depth charges were dropped 150 ahead of the conning tower. The U-boat went under and the two depth charges exploded. The pilot continued to circle and was joined by another aircraft. He could no longer see the men in the water but he did see pieces of wood rising and then an oil slick. The destroyer Ellis came over and dropped more depth charges and more oil came up. They did not sink the U-boat. It was later determined that the Ellis had depth charged a sunken ship and that was where the oil came from. Still the Coast Guard plane made a nearly successful attack on a U-boat and this was a harbinger of things to come.

With the success of the “Bucket Brigade” a 20% increase in escort vessels and aircraft was made and the first full convoy took place on May 11. On May 10 RADM Andrews sent a dispatch to his command outlining his expectations. Very little had been left to chance; including air support. A circle with a radius of 20 miles was patrolled around the ships and searches were to be made along the track of the convoy 25 miles to each side. It was a south bound convoy leaving Hampton Roads and on the first day it was covered by planes from Langley Field and CGAS Elizabeth City. On the second day aircraft from Cherry point covered them at daybreak and then the convoy was picked up by aircraft from Wilmington and Charleston. On the third day the planes from Charleston accompanied the convoy all the way to Jacksonville and stayed there. On the fourth day planes from Banana River picked up the convoy and on the fifth day aircraft from the Coast Guard Air Station Miami took over. By the last of May a full convoy system had been established. During June Convoy escort and aircover, some of the aircraft newly equipped with airborne radar, were provided for coastal convoys from Halifax in the north to Key West in the south. ADM Doenitz had recognized in early May that the “American shooting season” as it was called in Germany was over. By use of submarine tankers placed in prearranged location he was able to deploy his submarines into the Florida Straits, the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

The Gulf of Mexico

The success of the “Bucket Brigade” also had an impact on ADM Doenitz. He strongly felt that it did not really matter where the enemy merchant ship was sunk because the shipping network was employed to accomplish a single objective. His strategy, therefore, was that his U-boats should be employed wherever the most merchant tonnage could be sunk with the least cost to his submarine fleet. Thus he began operations off the South Florida Coast and in the Gulf of Mexico. From May through August 1942 the Gulf Sea Frontier, consisting of the Gulf of Mexico, the northwestern Caribbean, most of the Bahamas, and the east coast of Florida from Miami up to Jacksonville was the deadliest place on earth for shipping. In the Gulf of Mexico alone, during a five month period, 58 ships of approximately 300,000 tons were sent to the bottom.

The Gulf Sea Frontier was formed to defend the southern coast from Jacksonville to Texas on February 6, 1942. The Seventh and Eighth Naval Districts headquartered in Key West and New Orleans respectively comprised the Gulf Sea Frontier under the Command of Captain Russell Crenshaw. The forces at his disposal were even less than RADM Andrews originally had at his disposal and they were overwhelmed by the events that followed.

The first ship sunk by a U-boat in the Gulf Sea Frontier was an American tanker, Pan Massachusetts. ADM Doenitz had moved his main point of attack southward to a position off the Florida coast. During the month of April 18 additional ships were sent to the bottom. During May, with the advent of RADM Andrew’s full convoy system extending down to Miami, the German U-boat emphasis switched to the Gulf of Mexico. The first U-boats U-506 and U-507 entered the Gulf of Mexico at the beginning of May to take up station southeast of New Orleans. There were six submarines operated in the Gulf during May and seven during June. They sunk 38 ships. The initial surface force to oppose this consisted of two Destroyers, nine Coast Guard Cutters of various sizes, a limited number of small patrol craft and unarmed Coast Guard Auxiliary vessels. Aircraft available consisted of Navy Patrol Squadron VP-81 flying six PBYs and a detachment of three B-18 bombers at Key West, nine Coast Guard OS2Us at St. Petersburg, six CG OS2Us and two armed JRFs, and the first of the armed J4Fs at Biloxi. There were in addition 8 unarmed aircraft.

In mid May RADM James L. Kaufman took command and began taking action. He felt the Keys were too remote and moved the Frontier offices to Miami which provided better communications with air and surface forces. He instituted a coastal dimout and patrolled for compliance. A hunter killer group concept was launched and additional forces were obtained. On June 13, after being pursued through the Bahaman Channel by a Key West Killer group consisting of two destroyers, the Coast Guard Cutter Thetis and Army B-18s, the U157 was sunk by the Thetis. The B-18s were equipped with early air to surface radar, not as effective as the later microwave radar, but nevertheless a welcome addition.

During 1942 and 1943 the Coast Guard air station at St. Petersburg flew patrols over Tampa Bay and its approaches both south and north. The air station had nine OS2U aircraft assigned capable of carrying a 325 pound depth charge under each wing. A detachment of three aircraft was maintained at Key West and a two plane detachment of OS2Us known as the ‘Port St. Joe Detail” flew patrols in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico in the area of Cape San Blas. The tanker Joseph Cudahy was sunk southwest of Tampa on May 4th and another ship off Cape San Blas on June 29th. Surprisingly this was the sum total off the west coast of Florida.

There were 10 U-boats that operated in the Gulf during July and 7 in August, usually for two week periods. This resulted in 27 merchant vessels sunk. Most of the sinkings were concentrated in an area south of the Mississippi River delta. This was the mid point of the patrol area assigned to the Coast Guard air station at Biloxi. The Biloxi patrol area extended from a position east of Mobile Bay to the Galveston area.

Aircraft assigned to Biloxi were two unarmed Hall boats, Two JRFs with depth charge racks, and six OS2U-3s. J4Fs began to arrive. Five brand new ones were assigned to an air detachment at Houma, Louisiana in the first part of July in order to be closer to the patrol area and provide better coverage of the Mississippi River delta and the western Gulf of Mexico. There were no quarters or messing facilities so personnel lived on the local economy.

Operating from a grass strip, the detachment flew five, four hour, anti-submarine patrols each day. The aircraft carried a single 325 aerial depth charge under the wing. There was no storage for depth charges at Houma, so once they were attached to the aircraft they remained there until used or removed for major maintenance. Light maintenance was performed by the flight crews but when major maintenance was required the aircraft were flown to Biloxi for the work and then returned to Houma. Another detachment, using six OS2U-3s was established at Barataria Bay which is just west of the Mississippi River Delta south of New Orleans. They also flew five, four hour, anti-submarine patrols a day. Operations were from the water and the USS Christiana, YAG-32, a converted auxiliary vessel, serving as a seaplane tender, supported the aircraft. The planes were moored to buoys between missions. Personnel lived on board the Christiana. Again the aircraft were flown to Biloxi for major maintenance.

On 1 August 1942 Chief Aviation Pilot Henry C. White with RM1 George H. Boggs as his sole crewmember was flying the afternoon patrol. They were at 1500 feet at the base of a broken cloud deck 100 miles south of the Houma base. Through the open windows of their twin-engine Grumman J4F-1 Widgeon amphibian they could see about 10 miles across the hazy gulf sea. White had just turned to the northeast to set up a ladder search for the assigned area and moments later they saw a surfaced German submarine. White started to maneuver the Widgeon behind the sub for a stern attack but it immediately became obvious that as soon as White and Boggs had seen the sub, the sub had seen them, and the U-boat began to slide underwater in a crash dive. White banked sharply to starboard and from a half mile away began his dive towards the sub fully aware that he had only a sole depth charge under his wing and that he would have but one try. At an altitude of 250 feet the single depth charge was released. Boggs stuck his head out of the window and watched the depth charge fall into the Gulf waters, its fuse set to explode 25 feet below the surface. He estimated it entered the water 20 feet from the submarine on the starboard side. Boggs saw a large geyser of water rise from the explosion. White later wrote that the submarine was visible during the entire approach being just under the water and still clearly visible when the depth charge was released. When they circled back around they saw only a medium oil slick. German records obtained after the war verified that the U-166 had been sunk in that area during at the beginning of August. White and Boggs were given credit for the sinking.

Note: In 2001, the U-166 was discovered near the wreck of the SS Robert E. Lee a vessel attacked and sunk by the U-166 on 30 July 1942 about 45 miles south of the Mississippi River Delta and well away from White’s reported position when he attacked a U-boat. The Lee’s escort, USS PC-566, reported attacking a U-boat after the patrol craft’s crew sighted a periscope minutes after the Lee was torpedoed. After dropping depth charges near where the crew had seen the periscope, they reported spotting an oil slick. The commanding officer of the PC-566 claimed that they had damaged the attacking U-boat in his report of the action.

Bottom searches of the area of the reported attack by the USCG J4F Widgeon have been made by civilian divers and no wreckage of any kind has been found. Interestingly, another U-boat, the U-171, reported coming under attack by an Allied aircraft on 1 August 1942 in the general area of that White reported attacking a U-boat. The U-171 was sunk prior to the end of the war and the ships log is not available for verification

Additional assets became available and by the end of July a full convoy system was in place. In addition the Army Air Force Anti Submarine Command had supplied additional aircraft for patrol and convoy escort. The convoys proved effective and the number of sinkings decreased. There were seven sinkings in August and one in September. Doneitz redeployed assets to the North Atlantic and to the trade routes coming along the African Atlantic Coast.

The submarine battle of the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts was essentially over. The Last German submarine left the Cape Hatteras area on 19 July and the last of the U-Boats left Gulf of Mexico during the first part of September 1942. From February through December of 1943 there were one or at times two U-Boats that reappeared, however, during this 11 month period only four vessels were sunk. Singular U-Boats also returned during 1943 and mined the approaches to the East Coast and Gulf Coast ports. Sporadic sinkings did occur but they were far fewer in number.

The West Coast of the United States

The Japanese had the most diverse submarine fleet of any nation in World War II. The fleet included midget submarines, medium-range submarines, long-range fleet submarines with ranges exceeding 20,000 miles, and submarines that could carry and launch aircraft. They built 110 submarines capable of submerged speed 16 knots and a surface speed of 23 plus knots. In addition they employed the Type 95 torpedo which gave them three times the range of the Allies.

Considering the advantage in range, speed, and torpedo capability, Japanese submarines achieved surprisingly little. This, in large part was due to Japanese naval doctrine which employed the submarines against enemy warships and also the use of them as screening forces ahead of fleet movements. This approach brought success in 1942 when they sank two carriers, one cruiser, and several destroyers plus inflicting damage on two battleships, one carrier on two different occasions, and a cruiser. However, as the Allied anti-submarine technologies, methods, and numbers improved the submarines were never again able to achieve this level of success.

Japanese activity on the West Coast during the months immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor was limited to submarine operations. In a pre-war operations order dated 5 November 1941 the Japanese Navy had directed its Sixth Fleet to conduct submarine reconnaissance of the American Fleet along the West Coast of the United States and conduct surprise attacks on American shipping. A detachment of nine modern submarines, seven equipped to carry small patrol planes, arrived off the coast and dispersed to nine stations from Cape Flattery in the North to San Diego in the south. They stayed on station for a two week period. During this time two tankers were sunk off the California coast and another was shelled. A forth tanker was shelled off the mouth of the Colombia River. The detachment withdrew and there was no further activity off the coast until February 1942.

Navy Patrol Wing Eight had the responsibility for training and ASW warfare on the West Coast. The aircraft available were initially limited as the majority of VP squadrons were being deployed to the Pacific. Squadrons operated OS2Us, PBYs and PV Hudson Bombers based primarily out of San Diego and Moffet Field. The Army Air Corps provided two heavy bombardment squadrons and three light bombardment squadrons for ASW purposes. The Coast Guard had three Air stations on the West Coast – San Diego; San Francisco; and Port Angeles.

Coast Guard Air Station San Diego experienced little expansion and little change in function during the period leading up to the fall of 1943. The station had two

The aircraft was also operated as a seaplane

unarmed Hall Boats, a PH-2 and a PH-3, one RD-4 Dolphin and three J4F Widgeons, capable of carrying 325 pound aerial depth charges, assigned. They provided search and rescue services and occasional convoy escort assignments, flew a Channel Island Patrol, a Mexican Coast Patrol, and performed utility and administrative missions for the Navy. The Navy VP squadron at North Island was assigned the ASW duties for the area. Search and rescue missions remained primary and this experience made Coast Guard Air Station San Diego the ideal choice for the Navy’s first designated Search and Rescue Squadron in the fall of 1943. By August 15, 1945 (Japanese surrender) the number of SAR aircraft assigned totaled 12 of which seven where PBY-5As assigned to the SAR unit.

Coast Guard Air Station San Francisco was formally dedicated on February 15, 1941. In the years immediately prior to World War II the volume of marine and air commerce increased dramatically in the San Francisco area. There were two Coast Guard air stations on the west coast at the time; San Diego, 440 statute air miles to the south and Port Angeles 750 statute air miles to the north. Immediately after Pearl Harbor anti-submarine patrols began with the unarmed aircraft assigned to the station. In April of 1942, the station came under the command of the Western Sea Frontier. A squadron of Navy OS2U-3 aircraft was attached to the base and six additional Coast Guard OS2U-3s were provided for the air station operations. It was in practice a joint operation and on a number of occasions missions were flown with mixed crews. The area of responsibility was the Bay and approaches to San Francisco as well as inshore patrols both north and south of the Bay.

Coast Guard Air station Port Angeles saw rapid growth during World War II. The Navy established a Section Base, an aircraft gunnery range was established, anti submarine patrols commenced, and a short runway was constructed to train Navy pilots to land on aircraft carriers. Initial ant-submarine patrols were flown with unarmed aircraft. The J2F-1s were equipped to carry aerial depth charges and J4F-1s and JRFs were assigned and also equipped to carry aerial depth charges. The air station patrolled the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the inshore area off the coast. Coastal detachments were set up at Neah Bay and Quillayute, Washington In 1943 the station was equipped with the land-plane version of the SO3C-3. The performance was less than satisfactory and all were retired from service by March 1944.

Two Japanese submarines arrived off the West Coast during February 1942. The first, the I-8 patrolled northward from off San Francisco to the Washington coast without taking action against any shipping and then returned to Japan. The second arrived off San Diego on the 19th of February and on the 23rd it surfaced off the California coast near Santa Barbara and fired thirteen rounds of 5 ½ inch shells at oil installations. The damage was negligible. After this attack the I-17 proceed north to a point off Cape Mendocino in northern California and then returned to Japan. On June 7 the SS Coast Tracker was sunk by I-26 south of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. A Port Angeles J4F spotted the survivors and directed a Canadian Corvette to the rescue site. The I-26 shelled the radio station at Estevan Point, Vancouver Island on June 26 and the I-25 shelled Fort Stevens, Oregon on June 21.

On September 9,1942 the Japanese submarine I-25 surfaced near the Cape Blanco Light House, close to Port Oxford, about 60 miles from the California-Oregon border. The intent was to cause panic along the Pacific Coast. On the fore deck of the submarine was a hangar containing a disassembled single engine Yokosuka E14Y1 “Glen” seaplane. The aircraft was assembled, armed with two 170 pound phosphorus fire bombs, and launched. Its mission was to drop the incendiaries among the giant forest of the Northwest triggering a vast firestorm. The aircraft flew inland over the Siskiyou National Forest. Everything was concealed by a dense fog so it was not possible to see the point of impact when the bombs were released. It had been foggy and rainy for a period of time and the forest area was very wet. Possibly this is the reason that the forest did not ignite. The aircraft returned to the I-25 and just as the crew had finished putting the aircraft back in the hangar the submarine was attacked by an army anti-submarine patrol aircraft. The 1-25 crash dived for safety sustaining only minor damage. Daringly the submarine sought refuge in the Port Oxford harbor and remained motionless on the bottom. Two days later the I-25 slipped out to sea. The I-25 mounted a second attempt on September 29. Japanese Navy records indicated that the pilot observed flames on the ground after this attack. The bomb did start a small fire which was quickly extinguished.

On October 4 the freighter SS Camden was sunk off Coos Bay Oregon and on October 6 the tanker SS Larry Doheny was sunk off Cape Sebastian. These attacks marked the end to direct enemy activity off the west coast of the continental United States.

Many have argued that the Japanese submarine forces would have been better used patrolling allied shipping lanes. It would seem reasonable that an all out blitz of the American west coast during the period that this country was desperately building up its Pacific forces would have had caused great difficulty. Losing a significant number of merchant ships in addition to those sunk by the Germans would have required the spreading of the meager defenses even more thinly and would have had substantial consequences for the United States.