In October 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union came to the brink of nuclear war over the placement of Soviet missiles in Cuba. The United States armed forces were at their highest state of readiness ever and although not known at the time, Soviet field commanders in Cuba were prepared to use battlefield nuclear weapons to defend the island if it was invaded. For 13 tense days, a fragile peace hung by only a thread as the United States instituted a naval blockade of Cuba to turn back Soviet ships. The crisis was ended when the Soviet Union agreed in a secret negotiation to remove its nuclear weapons from Cuba in exchange for a U.S. agreement to remove its nuclear weapons from Turkey six months later.

In October 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union came to the brink of nuclear war over the placement of Soviet missiles in Cuba. The United States armed forces were at their highest state of readiness ever and although not known at the time, Soviet field commanders in Cuba were prepared to use battlefield nuclear weapons to defend the island if it was invaded. For 13 tense days, a fragile peace hung by only a thread as the United States instituted a naval blockade of Cuba to turn back Soviet ships. The crisis was ended when the Soviet Union agreed in a secret negotiation to remove its nuclear weapons from Cuba in exchange for a U.S. agreement to remove its nuclear weapons from Turkey six months later.

The Soviet Union was desperately behind the United States in the arms race. Soviet missiles were only powerful enough to be launched against Europe but U.S. missiles were capable of striking the entire Soviet Union. In late April 1962, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev conceived the idea of placing intermediate-range missiles in Cuba. A deployment in Cuba would double the Soviet strategic arsenal and provide a real deterrent to a potential U.S. attack against the Soviet Union.

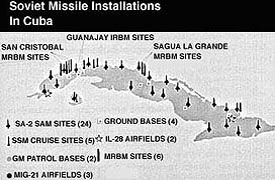

Meanwhile, Fidel Castro was looking for a way to defend his island nation from an attack by the U.S. Ever since the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 Castro felt a second attack was inevitable. Consequently, he approved of Khrushchev’s plan to place missiles on the island. In the summer of 1962 the Soviet Union worked quickly and secretly to build its missile installations in Cuba.

It was known by the United States that defensive missiles had been introduced into Cuba as well as IL-28 bombers. Offensive weapons were suspected and on 6 October U.S. Military forces were brought to a state of increased readiness. A U-2 flight over Cuba on 14 October produced the first hard evidence that offensive missile sites were under construction in Cuba. Intelligence agencies also confirmed that numerous Soviet Vessels were enroute to deliver what was believed to be missiles and missile parts.

It was known by the United States that defensive missiles had been introduced into Cuba as well as IL-28 bombers. Offensive weapons were suspected and on 6 October U.S. Military forces were brought to a state of increased readiness. A U-2 flight over Cuba on 14 October produced the first hard evidence that offensive missile sites were under construction in Cuba. Intelligence agencies also confirmed that numerous Soviet Vessels were enroute to deliver what was believed to be missiles and missile parts.

During the next very tense days, all options, including the invasion of Cuba were evaluated. The final decision was to impose a U.S. Naval “quarantine” of Cuba. (The word “blockade” was not used because it would be considered an act of war). President Kennedy said the missiles sites must be removed and he was prepared to use force if necessary.

.

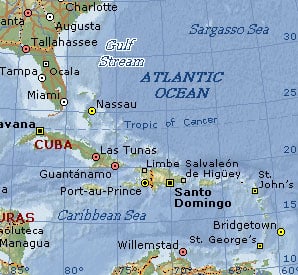

On Oct. 23, U.S. naval ships took positions on the quarantine line at 25 degrees N and provisions for aerial surveillance flights were put in place. The USS ESSEX with two S2F squadrons was assigned to patrol the zone north of 25 degrees. P5M’s of VP-49 and VP-45 were tasked with the zone north and east of 25N, 65W. VP-5 based out of Roosevelt Roads was tasked with the zone east of the quarantine line and south of 25N. The U.S. Coast Guard Miami Air Station was tasked with the zone that extended west from the Tortugas along the northern coast of Cuba and then northerly through the Bahamas to 25N.

Air Station Miami was immediately supplemented with additional HU-16E aircraft, crewmembers and maintenance personnel from other air stations throughout the Coast Guard. The patrol zone was broken down into patrol areas and designated as Red – Green – and blue patrols. The patrol surveillance flights were 5-8 hours long and there were usually 2-3 aircraft on these patrols. Pictures were taken of all vessels and all surveillance information was forwarded to intelligence agencies. It was a 24 hour a day operation. It is important to point out that during this period that the Air Station Miami retained the responsibility for Search and Rescue operations throughout the entire area. At the time, this was the largest operational mission the Coast Guard had ever flown. The air station, located at Dinner Key could not support the operation without a supplemental facility so operations were also conducted from the former Marine Corps Air Station at Opa-Locka.

On Oct. 26, Khrushchev pledged to remove the missiles if the U.S. guaranteed it would not invade Cuba. Kennedy agreed ending the immediate crisis. Verification was needed however so the President ordered the quarantine line be maintained and low level surveillance flights be continued while details were made for removal of offensive weapons from Cuba. The Coast Guard continued to make patrols.

On November 21: Just over a month after the crisis began, The President terminated the quarantine when Khrushchev agreed, after several weeks of tense negotiations at the UN, to withdraw Soviet IL-28 nuclear bombers from Cuba. Three decades later a Soviet military official would reveal that mobile tactical nuclear weapons and more than 40,000 Soviet troops were in place in Cuba for use in the event of an American invasion.

Supplemental Coast Guard aircraft and crews returned to their home air stations at the end of November but the continuing operational responsibilities at the Miami Air Station would remain larger than before. The end of the missile crisis brought on expanded rescue operations related to Cuban immigration which was not encumbered at the time. The number of people leaving Cuba would increase steadily over the next several years using any means available reaching a climax when Castro allowed well over 3000 people to leave the port of Camarioco. It also became apparent that the water only facilities at Dinner Key were not capable of supporting the Coast Guard mission and the air station moved to Opa-Locka in 1965.