The start of maritime drug smuggling was prompted by a demand for marijuana in America that could not be met by the land supply from Mexico. Initially marijuana smuggling was conducted by a large number of entrepreneurs, usually Americans, using fishing vessels, sailboats and cabin cruisers. Florida was closest to the developing marijuana sources and the coast from Miami to Palm Beach was an ideal off-load area. Fishing vessels and cabin cruisers could make the run from South Florida to a supply point in Jamaica in forty-eight hours. Key West also became a major marijuana port of entry. There were over 400 shrimp and lobster boats home-ported out of Key West; hundreds of miles of mangrove shore line and countless small uninhabited islands that were perfect off-load sites for marijuana bales. The shrimp boats had the range for non-stop trips to Colombia and below-deck capacity to carry large amounts of marijuana. It was common for American shrimpers to transit to and from the shrimp grounds off Central and South America. The ability to make more than a year’s wages with one or two marijuana runs was more than many could resist.

Marijuana smuggling changed dramatically in the mid seventies. In 1975 the Mexican government agreed to an aerial drug crop eradication program using the herbicide 2-4-D. The primary goal was to spray the poppy fields to reduce opium production but was spread to marijuana resulting in a “poisoned’ supply. The Marimberos, as they called themselves, of Colombia’s North Shore, who had been in various smuggling operations for years, stepped into the void. In order to meet demand a substantial capacity increase, best provided by maritime transportation, was needed. The Marimberos expanded their operation from production and packaging to include transportation and distribution. A mother-ship concept, similar in operation to that used during Prohibition, was set up using small freighters. Marijuana smuggling became highly organized and the product was delivered in multi-ton quantities. The independent operator surrendered the trade to multi-national groups who had volume capabilities.

There was a great deal of reluctance on the part of some senior Coast Guard Officers to be become involved in drug interdiction. Many did not look favorably upon becoming a maritime police agency engaged in a program which at the time did not have a public consensus. The Coast Guard had been transferred to the Department of Transportation and the service was focused on its lifesaving and other missions. The historical roots of the organization, however, were the enforcement of revenue laws. Despite this reluctance, the Coast Guard became the lead agency for maritime drug interdiction. Admiral Owen Siler, Commandant of the Coast Guard, during this early period, addressed profound changes in law enforcement at an unprecedented rate.

By 1976 large amounts of Colombian marijuana were reaching the United States in the mother-ships. These large vessels carried bulk shipments of marijuana to prearranged points off the U.S. Coast. The ships moored far enough away from shore to avoid notice, and off loaded their cargo to small boats and fishing vessels that could smuggle the drug ashore less conspicuously and avoid detection. During the early part of the year, Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) aircraft flew surveillance flights up and down the coast of La Guajira, Colombia, a major embarkation point for marijuana smuggling operations. Ships were loaded right off the beach in a scene that resembled a World War II amphibious operation. Trucks ran between warehouses and the beach. Bales were loaded by means of floating platforms or directly up ramps to the vessels. The DEA aircraft identified the vessels and reported the information to the DEA’s El Paso Intelligence Center, which then relayed the information to the Coast Guard.

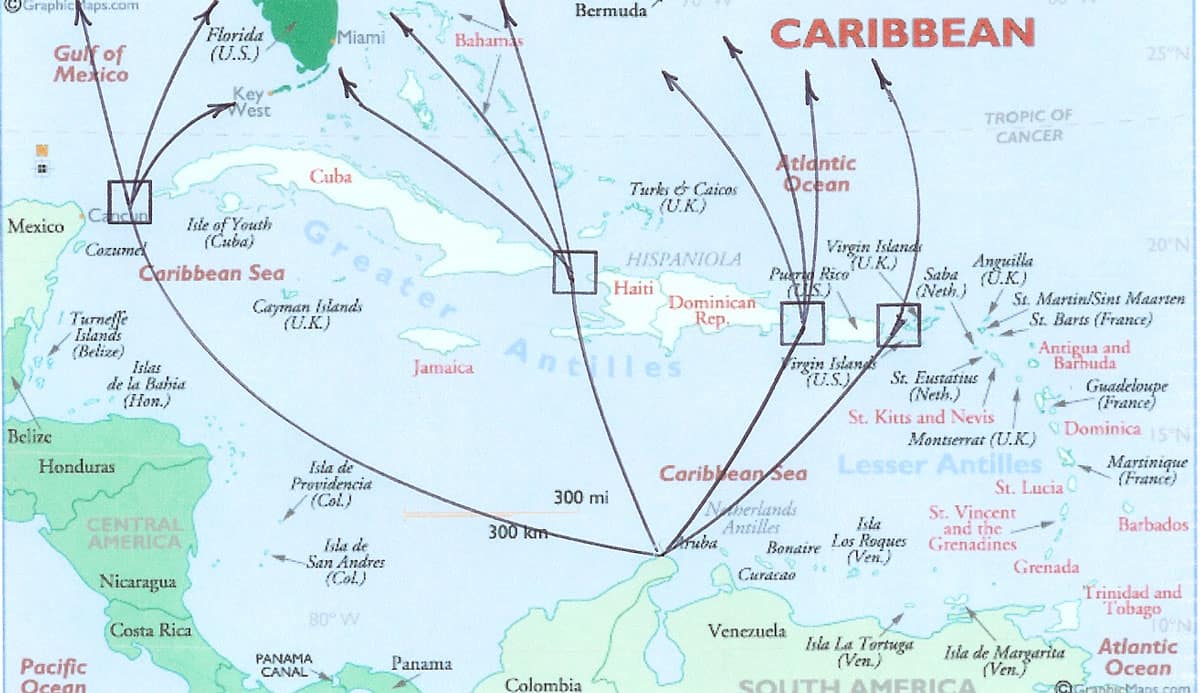

The Coast Guard developed an interdiction system whereby existing assets could be concentrated to intercept a transporting vessel prior to it reaching its destination. In order for a vessel, leaving the La Guajira Peninsula on the north coast of Colombia, to reach drop-off areas adjacent to the United States they had to transit one of four passages through the islands of the Caribbean. These passages were referred to as choke points. Cutters took up station at a choke point. Helicopters were placed on flight-deck equipped cutters greatly increasing coverage and effectiveness. Fixed wing aircraft flew surveillance flights in support of the cutters. They also patrolled the potential drop points. Intelligence information provided by the Drug Enforcement Agency significantly increased the interdiction rate.

The Coast Guard efforts became increasingly effective and began to make serious inroads into the drug operations. The smugglers adapted their operations to counteract this. By 1980 Marijuana smuggling had evolved into a highly efficient business. Operations were conducted according to specialized divisions of labor and expertise. Off load coordinates were passed at the last minute utilizing alpha-numerical codes. Air surveillance was used by the smugglers to ensure an off load point where a Coast Guard cutter was not present and high speed chase boats would check out the off-load area just prior to the arrival of the mother-ship. Marijuana, once carried openly, now began to be transported in hidden compartments. In spite of this, the Coast Guard choke point strategy, utilizing a combination of aircraft and surface vessels, was able to interdict a growing number of smugglers before they got to their off-load points. This strategy became know as Operation STEEL WEB.

The Coast Guard efforts became increasingly effective and began to make serious inroads into the drug operations. The smugglers adapted their operations to counteract this. By 1980 Marijuana smuggling had evolved into a highly efficient business. Operations were conducted according to specialized divisions of labor and expertise. Off load coordinates were passed at the last minute utilizing alpha-numerical codes. Air surveillance was used by the smugglers to ensure an off load point where a Coast Guard cutter was not present and high speed chase boats would check out the off-load area just prior to the arrival of the mother-ship. Marijuana, once carried openly, now began to be transported in hidden compartments. In spite of this, the Coast Guard choke point strategy, utilizing a combination of aircraft and surface vessels, was able to interdict a growing number of smugglers before they got to their off-load points. This strategy became know as Operation STEEL WEB.

The use of foreign and stateless ships became the mode of operation. In order to take enforcement action against a foreign vessel a Statement of No Objection (SNO) was required. Under the terms of the 1958 Geneva Convention, one nations naval or Coast Guard unit must receive permission from another nations government to board the latter’s vessel on the high seas. The procedure to obtain this was cumbersome but the procedure had been developed in the 1960’s for foreign fishery enforcement boardings and the SNO was usually obtained within a few hours. If the vessel was determined to be stateless or if the Master of the suspect vessel gave permission to board, no SNO was necessary. If contraband was found after a consensual boarding, a SNO was necessary to seize.

A number of events, starting in 1980, provided significant help in interdiction efforts. The Biaggi Act (21 USC 955a) expanded U.S. jurisdiction over U.S. and stateless vessels and the Cuban boatlift ended thus freeing up Coast Guard resources. In December of 1981 Congress amended the Posse Comitatus Law to enable the military to give indirect assistance to law enforcement entities, including sharing of intelligence, use of military equipment and facilities, and training of civilian law enforcement personnel. Three former Navy salvage tugs were outfitted and commissioned as Coast Guard cutters and three Surface Effect Ships were obtained. In Miami, drug related crime had risen to the point where it finally caught the nation’s attention and President Reagan created the South Florida Task Force (SFTF) to coordinate the activities of all agencies involved in the drug war.

The Seventh Coast Guard district encompassing 1.8 million square miles of the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea and a portion of the Gulf of Mexico exercised operational control. In the period 1982- 1984 RADM D.C. “Deese” Thompson, US Coast Guard was Commander of the Seventh Coast Guard District and the SFTF coordinator. Secretary of the Navy John Lehman authorized the Navy to support the Coast Guard with air and surface surveillance, towing or escort of seized vessel, embarkation of Coast Guard law enforcement details on naval vessels, and logistic support to Coast Guard units. RADM Thompson went to COMPATWINGSLANT and briefed the P-3 community on what the Coast Guard was looking for. Their patrol tracks were modified to put them in the most likely areas for targets of interest. The P-3s carried a Coastguardsman onboard. Once the Navy units were committed they chopped to CCGD7 operational control. The Coast Guard LANTAREA sent additional high endurance cutters (WHEC) and medium endurance cutters (WMEC) and some patrol boats (WPB) from other LANTAREA districts. They also chopped in and chopped out. The Coast Guard, for the first time, was able to maintain an almost continuous presence at all choke points. C-130s were made available when not tasked for other operations. HH-52s were sent out with the WMECs and WHECs within the limits of availability and as rapidly as pilots could be qualified for night shipboard operations.

A number of the WMECs and WHECs were forced to take up station without a helicopter aboard. There were not enough helicopters in CGD7 to provide both SAR coverage and shipboard interdiction operations. Additional helicopters from other Coast Guard Districts were assigned on a temporary basis for specific periods of time but there was reluctance on the part of the aviation community to regularly deploy them. Each helicopter temporarily assigned to a WMEC or WHEC for drug interdiction in CGD7 directly affected the mission capabilities of the units designated to deploy them. There had been significant mission creep with no additional aircraft and no funds to procure them. Commandant Hayes had just recently been in a battle with the Bureau of the Budget (OMB) whose intent was to drastically reduce the Coast Guard budget and civilianize major portions of the Service. There just was not enough aircraft to adequately cover the missions the Coast Guard had been given.

Despite political posturing, fears of a military takeover, continuing interagency rivalries, and differences in emphasis, the SFTF provided a degree of multi-agency coordination not previously obtained. The Vice President made regular visits and as SFTF coordinator RADM Thompson would brief him. President Reagan paid a visit in November 1982 to reassure South Florida that actions were being taken to coordinate a more effective effort against “drug smugglers and the narco thugs.” RADM Thompson as SFTF coordinator briefed him on board the USCG Dauntless moored at the USCG Base Miami Beach, Florida. Drew Lewis, the Secretary of Transportation, called RADM Thompson the day before the briefing to make it known that he did not want him pressing for more USCG resources and requested a copy of the Admiral’s brief. The Admiral told him that he was not

speaking from a brief. RADM Thompson commented, “The President asked me several direct questions. The briefing room was secure and there was no note taking, so we had a very fruitful and candid discussion of our strategy, tactics, and need for more assets for us and better cooperation from some of the reluctant agencies.”

The incentive to engage in large scale maritime marijuana smuggling operations was generated by the enormous profits that could be realized. Good grade Colombian marijuana was purchased at the supply end for $35 a pound. The cost of a pound of marijuana at wholesale in the Southeast United States averaged out at $450 a pound. The average mother ship carried between 10- 15 tons of marijuana. A shipment of 24,000 pounds would generate a gross profit of almost 10 million dollars. The mother ship had a Captain, an Engineer and depending on the size eight to ten crewmembers representing a cost of $350,000 for manning and operating expenses. Aircraft surveillance would run about $275,000. A chase boat and off-load boats would add another $250,000. Handlers and off-load storage another $200,000. A payment of 1 million went to a middleman. The principals still made $7.88 million on each successful two–to-three-week round trip.

Although it was not realized at the time, the years 1982-1983 marked the turning point in maritime drug interdiction operations. The Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces were created to go after key traffickers and their money sources. The SFTF concept was expanded and the National Narcotics Border Interdiction System (NNBIS) had been created bringing the Department of defense and the national intelligence community assets into the drug war. The Coast Guard manning choke points on a continuous basis, with valuable assistance from the Navy, became very effective in interdiction operations.

Drug interdiction on the West Coast was considerably different than the Caribbean and the Atlantic areas. There were no natural choke points that smuggling vessels had to pass through. Initially, off-shore drug patrols, using 82-foot and 95-foot patrol boats were regularly conducted. Admiral Gracey, COMPAC at the time, stated they were not effective so they were discontinued and reliance was placed on over-flight patrols conducted by aircraft. The homeports of the patrol boats were moved to locations that enabled them to arrive on scene rapidly if intelligence dictated or a suspected smuggler was spotted by an aircraft. He went on to say that occasional patrols were made to establish a presence. In addition C-130 aircraft were deployed to Howard Air Force Base in Panama and flew patrols along the Panamanian, Colombian, and Ecuador coasts looking for ships that fit the profile. When one was found it was trailed until a destination was established. This was possible with the existing limited assets because the drug smuggling was not near as intense as in the Caribbean.

The total maritime marijuana seizure statistics for the period 1977 through 1982 compared to 1975 reflects the tremendous increase in marijuana smuggling. It also indicates the increase in U.S. interdiction efforts. In 1978 almost 3 million pounds of marijuana was interdicted and 115 vessels were seized. During 1980 the Coast Guard was actively engaged in alien migrant interdiction but marijuana seizures remained high. During the last three months of the year 69 vessels were seized for a total of 101 vessels seized during the year. Seizures rose to 126 in 1981 and to 145 in 1982. The amount of marijuana seized also continued to increase peaking in 1982 at 3.5 million pounds. In 1983 there was 3.1 million pounds intercepted, 75% of which was intercepted in the Caribbean. The Coast Guard accounted for roughly 80% of that or 2.4 million pounds while seizing 99 vessels. The years 1984 and subsequent reflect the growing success of the interdiction forces efforts.

Note:

Peter Bourne, President Carter’s Special Assistant for Health Issues believed that Cocaine was not a health hazard. Emphasis of the DEA was on Heroin. The smuggling of cocaine grew exponentially when Carlos Lehder and the Medellin Cartel developed a sophisticated air smuggling operation through the Bahamas in 1980. This part of the cocaine smuggling operation is addressed under the OPBAT heading in the Time Line. It was not until 1983 that cocaine smuggling also became a maritime problem.

The maritime drug interdiction went on the offensive in 1984 and this action is addressed in the Time Line under that heading. Coast Guard aviation flew maritime surveillance flights both fixed wing and shipboard helicopter since the beginning of the Coast Guard’s interdiction efforts.

Coast Guard air interdiction did not commence until 1987 and is addressed under that heading.