Before World War II there was little need for the Military to establish an extensive Air-Sea Rescue organization. Pan American World Airways had started trans-ocean flights with large flying boats but long over-water flights were limited. Traffic which was not coastal depended upon international shipping services for assistance. This was considered to be adequate.

Before World War II there was little need for the Military to establish an extensive Air-Sea Rescue organization. Pan American World Airways had started trans-ocean flights with large flying boats but long over-water flights were limited. Traffic which was not coastal depended upon international shipping services for assistance. This was considered to be adequate.

With advent of World War II this picture changed rapidly. During May and June 1940, the RAF, by official British accounts, lost 959 aircraft, including 477 fighters. The Royal Air Force fought the German Luftwaffe over Britain between the 10th July and 31st October in what came to be called the Battle of Britain. Fighter Command’s inventory totaled only 331 Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes. The British aircraft industry provided replacements for the aircraft losses but as combat attrition continued the absence of an effective rescue capability became critical since the downing of aircraft in the Channel or North Sea usually meant the loss of combat experienced aircrews.

Rapid progress in rescue capability was made and by September 1941 a Deputy Directorate of Air-Sea Rescue was established supporting Fighter, Coastal, and Naval Commands. Numerous aircraft and surface rescue boats were provided for full time rescue duty; a communication network was established to handle distress calls; survival equipment was placed aboard aircraft; operating procedures were established; and a specialized rescue training school was established at Blackpool.

In 1941 the Army Air Force (AAF) was not prepared nor equipped for rescue operations at sea. Help came from the U.S. Navy and the British. The Navy readily provided assistance; however, Navy policy was that rescue efforts were not to interfere with operations. By formal agreement with the Royal Air Force it was stipulated that the AAF would not duplicate Britain’s well-organized and experienced air-sea rescue service. American crews were protected by the existing British service over the English Channel, the North Sea, North Africa and the waters off India and Burma. The U.S. Coast Guard had developed some of the aspects of the British system prior to the war but facilities were local and the practice of diverting commercial surface craft in cases of forced landings at sea had experienced parallel growth with prewar aviation advancement.

As of the spring of 1943 the scale of the AAF combat operations was no longer limited enough to allow the continued dependence upon the assistance of others for air-sea rescue. The Navy was experiencing a growing requirement with the expansion of the war in the vast area of the Pacific Ocean. Added to the normal hazards of war was a pilot training program that had grown exponentially. As a result forced landings and ditchings increased substantially. The problem of achieving better co-ordination of effort between the Navy and the Army Air Force, and a closer liaison with interested Allied services was addressed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff. An integration of existing services promised savings in equipment and personnel and additionally would establish common rescue procedures among the Armed Services. There was agreement on the need for improvement but disagreement on how to achieve it.

The Navy argued that the rescue function should be turned over to the Coast Guard as a logical step based upon that services’ traditional mission. It was pointed out that the Coast Guard could supply a trained cadre of pilots and crews versed in over-water operation; personnel trained in small boat operations; and with existing and newly established shore stations; could effectively emulate the highly successful British model. It was further argued that, with the diminished submarine threat off the coasts of the United States, the Coast Guard could transition to an effective air-sea rescue force quickly. This proposal was fully supported by the Commandant of the Coast Guard, Admiral Russell R. Waesche, in a letter of 23 July 1943. The Army’s preference was to retain its own rescue forces with the establishment of a liaison committee providing coordination of efforts, procedures, and equipment.

The Air-Sea Rescue Agency

AAF arguments prevailed in the deliberations of the Joint Chiefs of Staff which concluded that the Coast Guard, despite its well earned tradition as a search and rescue organization, would face insurmountable obstacles should it have to expand its responsibilities to provide Air-Sea Rescue for both the Army and the Navy given the immediacy of the situation. It was recommended that the Army and the Navy continue the development of separate rescue services but that a new agency be established for their coordination. On February 15, 1944 the Joint Chiefs issued a memorandum which resulted in the Air-Sea Rescue Agency. It is quoted as follows:

“The Joint Chiefs of Staff request the Secretary of the Navy to establish an agency in the Coast Guard to:

(a) Conduct joint studies and assemble information on

(1) Technical data concerning research, development, and design of air-sea

rescue equipment.

(2) Methods, techniques, and procedures, including the adequacy of facilities

for air-sea rescue.

(b) Disseminate the forgoing information to the appropriate agencies of the War

and Navy department and to other interested departments, recommending

appropriate action in connection therewith.

(c. ) Maintain liaison with agencies of other United Nations (such as the British

Deputy Directorate of Air-Sea Rescue) concerned with these matters.

It is recommended that this agency be headed by the Commandant of the Coast Guard and assisted by a board consisting of:

(a) Two representatives from the Army Air Force

(b) One representative from the Army Service Forces

(c ) Two representatives from the Navy.”

The Agency was established as recommended. Agency committees reported directly to the board on the following subjects: (1) Emergency and survival  Publications; (2) Adequacy of Air- Sea Rescue Facilities; (3) Communication Facilities and Requirements for Air-Sea Rescue. (4) Special Aircraft Equipment for Rescue and Survival; (5) Life-saving on Transports; (6) Medical and Physiological Aspects of Air-Sea Rescue; (7) Ditching Procedures. Liaison with the air-sea rescue agencies of Allied nations was carried out through working contacts with their missions in the United States. Liaison with the services of the United States was maintained through liaison officers from the Agency attached to combat theater and frontier commands. The attached liaison officers were Coast Guard. AAF leaders, still fearing that the Navy wished to turn full Air-Sea Rescue responsibility to the Coast Guard, objected in that this could result in executive functions given to a body that had been designated as advisory. The Navy continued the practice as beneficial to those involved.

Publications; (2) Adequacy of Air- Sea Rescue Facilities; (3) Communication Facilities and Requirements for Air-Sea Rescue. (4) Special Aircraft Equipment for Rescue and Survival; (5) Life-saving on Transports; (6) Medical and Physiological Aspects of Air-Sea Rescue; (7) Ditching Procedures. Liaison with the air-sea rescue agencies of Allied nations was carried out through working contacts with their missions in the United States. Liaison with the services of the United States was maintained through liaison officers from the Agency attached to combat theater and frontier commands. The attached liaison officers were Coast Guard. AAF leaders, still fearing that the Navy wished to turn full Air-Sea Rescue responsibility to the Coast Guard, objected in that this could result in executive functions given to a body that had been designated as advisory. The Navy continued the practice as beneficial to those involved.

Air-Sea Rescue Agency projects were both practical and functional. The Committee to Study Special Equipment for Rescue and Survival was especially effective. The research and development activities of the Army, and Navy together with other agencies established by Presidential Directives were coordinated and numerous new equipment items were developed.

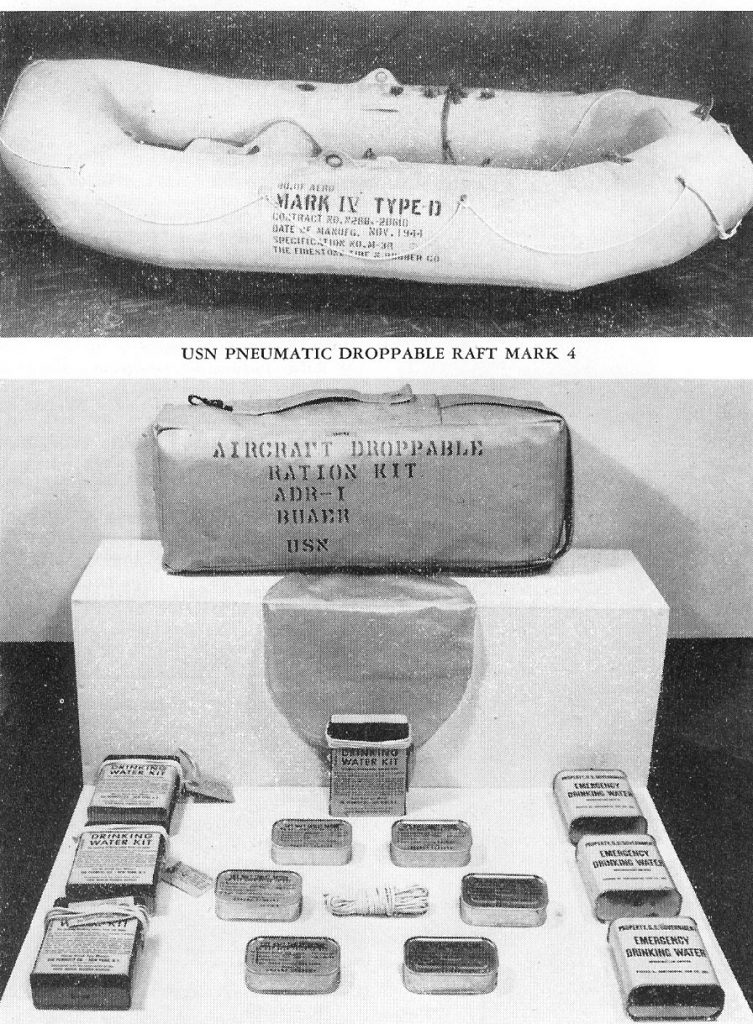

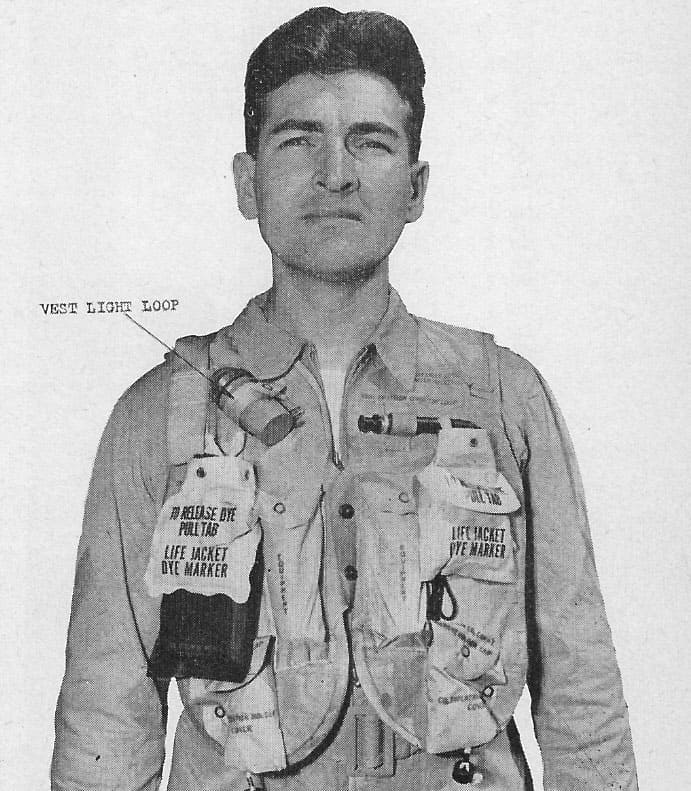

A quick donning exposure suit was developed for crews in multi-engine aircraft operating in the colder regions of the world. Sea Marker dye, which would spread in sea water forming a large splotch of bright color which improved greatly the probability of locating a survivor, was developed and each Mae West life preserver had a packet of it attached. Shark repellent packets were developed and also attached to the Mae West. An assortment of pneumatic rafts, tailored for specific needs and usage, were developed. These rafts contained emergency food rations, hand held mirrors that could be aimed, hand held orange smoke signals, hand held pyrotechnic signal pistols, radar target screen, a solar still capable of making 750cc of drinking water from the sea in an eight hour period, a chemical conversion kit capable of making five pints of water from sea water.

Several aerial delivery kits were developed by the AAF which could be dropped to survivors in all areas of the world providing a method of providing continuous equipment, food, water and medical supplies to sustain survivors until they were rescued. The Navy developed a shipwreck kit, rations kit, and signaling kit for the same purpose. A radio transmitter, called the “Gibson Girl” that automatically operated alternately on the distress frequencies of 500 kilocycles and 8280 kilocycles was developed to provide a means for searching aircraft and surface vessels to home in on the position of a survivor. This was carried on board multi-engine aircraft and was also packaged in a waterproof buoyant case that could be dropped by parachute to a survivor. The Coast Guard developed a delivery system that was shaped like a bomb. A long line was attached and strung out during delivery to facilitate retrieval.

Training in the use of the new equipment was also necessary. Operational Training Centers set up schools approximating as nearly as possible, tropics, arctic or open water conditions. Courses were designed to teach crewmembers the basic principles of living off the land and sea. Emphasis was placed upon individual survival. The fundamentals taught included; travel in all types of terrain; orientation; situation management; collection and the identification of plant and animal food; construction of shelters; preparation of food including fire making and cooking; and knowledge of the biological and physical hazards of the area in which the training was given. To these fundamentals were added the operation of emergency rescue equipment, procedures for ditching aircraft, bailout techniques, water survival, medical procedures, methods of communicating with rescue units, and hand-to-hand combat.

One program of the Air Sea Rescue Agency was to develop a distinctive, highly visible color scheme for ASR aircraft. The color scheme was overall aluminum with yellow wing tips, floats, the top of the wing between engines, patches beneath the pilots’ compartment, and a band around the aft fuselage. All the yellow markings were bordered with black, and the word RESCUE in black letters, was painted in the yellow area between the engines. Eventually, all Coast Guard aircraft utilized these colors, as did the Air Rescue Service of the U.S. Air Force, until the 1960s, at which time both services adopted different paint schemes.

The Air-Sea Rescue Agency was renamed the Search and Rescue Agency in 1946. It continued to be headed by the Coast Guard until its disestablishment in 1949 when events superseded it. The Coast Guard proved to be an excellent choice to head up this agency. Because of the uniqueness of the Service it was able to promote coordination and cooperation among the various military and civilian organizations thus making the Air-Sea Rescue Agency both effective and worthwhile.

ADM Russell R. Waesche, Commandant of the Coast Guard and head of the Air-Sea Rescue Agency, very clearly outlined the importance the Agency played during World War II when he said; “Our aviators and seamen, with confidence that they will fly and sail again, dare to face greater odds in the war today. Vision of the Services, and ingenuity of industry have provided survival and rescue equipment, which has lessened the hazards, improved the safety, and given our men greater courage. May we never be content with the present equipment, but constantly improve it with experience, continued study, and cooperative effort.”

Air-Sea Rescue Operations

In the fall of 1943 the AAF drafted plans to organize seven Emergency Rescue Squadrons (ERS). Each squadron was to be equipped with PBY-5As for rescue operations, Stinson L5s for liaison and Beechcraft AT-7s for utility purposes. The schedule called for the squadrons to be operational by the spring of 1944. Most of these units were scheduled to support the Pacific Air Forces and rescue support for the Air Transport Command. Initial PBY training was provided by the Navy at NAS Pensacola. This formed the nucleus for the establishment and training of the 1st ERS at Boca Raton, Florida and the 2nd ERS initially at Hamilton AAF California and then Keesler AAF, Biloxi, Mississippi. Delays were incurred during training and squadron implementation. The AAF had procured Canso PBYs (OA10) manufactured by Canadian Vickers. Hull reinforcement was required to prevent damage during water landings resulting in a shortage of aircraft. There were very few personnel experienced in small boat handling and training had to be conducted. As a result there were only two ERS squadrons in operation by the summer of 1944. Another became operational in the Southwest Pacific by the end of the year but the others did not achieve that status until mid 1945.

During 1943 the Navy added rescue duties to the missions of the patrol squadrons in the Pacific. The Navy, because of its expanded training programs, was also experiencing a high number of aviators being forced down on numerous over-water flights. RADM David Bagley, Commander Western Sea Frontier and 11th Naval District was well aware of the situation when he was approached by Commanders Max Black, USN and Watson Burton USCG with a plan to organize the Coast Guard San Diego air station as an air-sea rescue unit similar to the British model. The San Diego air station, except for occasional convoy escort duty, had been used primarily for utility and search and rescue duties. The plan was approved by RADM Bagley and operations began in December with the first of seven PBY-5As and high speed Air-Sea Rescue boats. The main base of operations was the San Diego Air Station with Air Sea Rescue detachments (ASRTU) placed at MCAS Goleta (Santa Barbara), NAAS San Nicolas and NAS Los Alamitos. Three PBM-3s, one PH3 and four J4Fs carried out the additional missions of the Coast Guard Air Station and supplemented the air station’s ASRTU. The San Diego ASRTUs, all Coast Guard, were the first Navy air rescue units designated as such and proved to be very successful. The Navy followed with three VH rescue squadrons that deployed to the Pacific. Between Jan 1, 1944 and December 1, 1945 124 aircraft went down in the San Diego area. Of the 201 pilots and crews involved, 137 were saved, 59 were killed by collision or impact with the water and five were lost because of lack of or improper use of equipment.

The Coast Guard had been given ASW duties within the Sea Frontiers beginning in early 1942. By mid 1943 the submarine offensive off the coasts of the United States had diminished significantly and the Coast Guard air stations experienced a gradual shift in emphasis back to a rescue mission operation. The ASR operations were based on the British system and Coast Guard Officers received training at the ASR school Blackpool, England. As air traffic and merchant marine operations increased in scope the number of planes and vessels requiring assistance increased accordingly. By the end of 1943 the Coast Guard air stations were operating primarily as rescue units.

In August 1944 the Chief of Naval Operations directed Naval Sea Frontier Commanders to establish centralized control for Air-Sea rescue operations. In the same month, Army authorities established Emergency Rescue organizations (ERS) at strategic points, particularly in Alaska and along Air Transport Command routes. The AAF additionally completed organization of its air-land rescue system with emphasis on the western mountain regions of the United States under the control of the Second and Fourth Air Forces.

The Chief of Naval operations further directed that, for the duration of the war, control of Air-Sea Rescue was to be effected through and as an integral part of the existing sea frontier facilities. Required operational units were to be supplied primarily by the Coast Guard. Rescue task units were established consisting of specially equipped and manned air and surface rescue craft under the operational control of the Commanders of the various naval districts within the Sea Frontiers. Coast Guard officers were assigned to the Sea Frontier staffs. Operational procedures and communication doctrine were established. The Commanding Officers of the nine major Coast Guard air stations were assigned as primary task unit commanders.

The air stations operated as control centers. Aircraft and crash boats were located at the parent air station and at assigned detachments strategically located throughout the Sea Frontiers. Within the Eastern Sea Frontier, for example; in addition to the three parent air stations there were 33 aircraft located at 16 different aviation facilities throughout the Sea-Frontier. As soon as a distress was reported immediate action was initiated. A determination of available assets was made. If a search was required to locate survivors then the last known position was obtained and using the know characteristics of the object searched for and the sea currents and present weather conditions, a most probable area of location was determined and rescue craft were launched. The air stations were part of the effective communication network. Specific search patterns and procedures were utilized. Coast Guard assets were primary but if assets of other services were closer or better able to perform the mission, a request was made directly to that organization. This at times could be awkward as the air station Commanding Officer was apt to be junior in rank to those that assistance was requested from. It was handled well.

In August of 1944, when the navy delegated the primary responsibility for SAR to the Coast Guard, Coast Guard aviation forces had 16 Grumman JRFs, 21 Grumman J4Fs, 18 Martin PBM-3s, and 20 PBY-5A aircraft available for Air-Sea Rescue duties. The Navy supplemented this by transferring 90 PBY-5As and 23 PBM-5s to the Coast Guard. In addition five PB4Y-1 Liberators and five PB2Y flying boats were supplied. Two of the PB4Y-1s were assigned to VP-6 and one replaced V-189 as the Loran survey aircraft. It is not known where the other two were assigned. The PB2Y Coronados were based out of San Francisco. Seventeen PB-1s (B-17s) were set aside for the Coast Guard but they did not arrive until 1946. There were 334 Aviators and Aviation Pilots on board at the end of August 1944, Over the next several months, in addition to current Coast Guard personnel assigned to flight training, the Navy commissioned 175 graduating Naval Aviation Cadets in the Coast Guard. By the end of December 1945, a little over a year later, the number of aviators and aviation pilots on board was 570. An extensive training program was organized and carried out. Close coordination with the Air-Sea Rescue Agency ensured that the latest equipment and procedures were utilized.

PB4Y-1

The PB4Y-1 was a Navy variant of the Army Air Force B-24D. It was initially developed to provide a long range land based patrol and ASW aircraft. Powered by four Pratt & Whitney R1830-65 engines it had a range of 2960 statute miles with a cruise speed of 215 mph. These aircraft were obtained in late 1944 and the last was retired from service by 1951.

PB2Y

Except for the retractable floats the Consolidated PB2Y was a totally different design than the PBY. It was a huge long range flying boat powered by four Pratt & Whitney R1830-88 engines. A production contract was placed in 1940 but production was limited because of emphasis placed on PBY construction during WWII.

Five PB2Ys were acquired by the Coast Guard in 1944 and were retired from service in1946.

On the first of December 1944 the Commandant of the Coast Guard established the Coast Guard Office of Air-Sea Rescue. This office was a component part of Coast Guard Headquarters established to deal with aspects of air-sea rescue operations of Coast Guard vessels, aircraft and shore stations. It should not be confused with the Air-Sea Rescue Agency which was a joint advisory and development committee under the direction of the Commandant of the Coast Guard.

During the 1942 period the Eastern Sea Frontier had been assigned the secondary function of providing rescue, assistance and salvage to vessels up to 500 miles off shore. In August of 1944 when the Commander Eastern Sea Frontier was directed to develop suitable methods and procedures to implement the Air-Sea Rescue program he elected to integrate existing sea frontier facilities into the procedures. Close and rapid coordination and dissemination of information as to the location and occurrence of distress was provided for. Shore based radar and high frequency direction finding equipment was utilized. A continuous Air-Sea Rescue Operations watch was established at a control center and manned by qualified Coast Guard watch standers. Air Sea Rescue Task Units were established at the Coast Guard Air Stations. Group operation plans were developed and communication channels were established. Assets included aircraft, 65 foot and 104 foot rescue boats, Coast Guard Cutters, and lifeboat stations. The operations center also maintained a continuous plot of all Merchant and Naval vessels within the frontier area. The coordination of Coast Guard, Navy AAF and civilian assets through a centralized operational control provided a very effective search and rescue operation and was the basis of future Coast Guard search and rescue organization.

The objective of the ASR organization was to first find the wrecked vessel or plane; to provide the survivors a means to remain on the surface of the water until help arrived; to provide food and water, and when required medical supplies, to keep survivors alive; and finally to transport them safely ashore. Properly equipped planes and rescue boats and vessels, manned by well trained crews worked together as an effective team. All rescue agencies operated as a basic unit once on scene. Normally the unit aircraft assumed command of all units. The aircraft on scene, unless the situation dictated that a landing be attempted, acted as a communication platform and directed surface vessels to the survivors. An excellent Coast Guard communications system contributed to the efficient and effective interaction of surface vessels, air stations, coordination centers, task unit commanders and on scene ASR units. The Coast Guard performed ASR well.

Although the Prime responsibility for ASR in Alaska was the responsibility of the AAF, the Coast Guard established an air detachment at Ketchikan on Annette Island and a parachute rescue unit trained by the U.S. Forest Service was based at Ketchikan. The helicopter was used very effectively on several occasions but was not assigned as part of the Air-Sea Rescue operations.