During WW-II the air-sea rescue had been primarily a military operation. The coordination of efforts had been a topic of the Joint Chiefs of Staff since 1942 and under discussion was whether a separate agency should be created for rescue operations or whether one of the existing services should be charged with primary responsibility. In July of 1943 VADM Waesche, Coast Guard Commandant, presented to the Joint Chiefs, factors qualifying the Coast Guard for this responsibility. He concluded his presentation by saying that air-sea rescue was a most proper and normal function of the Coast Guard. This proposal was strongly endorsed by the Navy and just as strongly opposed by the Army Air Force. A sub-committee, set up to evaluate the proposal, concluded that the Coast Guard would face insurmountable obstacles if it were to attempt to expand into all types of rescue activity for all military forces. It did, however, recommend a joint service Air-Sea Rescue Agency, headed by the Commandant of the Coast Guard, be established to analyze technical data, develop and design air-sea rescue equipment and procedures and to disseminate information to all parties engaged in search and rescue activities. It further stated that each service should retain responsibility for its own aircrews.

During WW-II the air-sea rescue had been primarily a military operation. The coordination of efforts had been a topic of the Joint Chiefs of Staff since 1942 and under discussion was whether a separate agency should be created for rescue operations or whether one of the existing services should be charged with primary responsibility. In July of 1943 VADM Waesche, Coast Guard Commandant, presented to the Joint Chiefs, factors qualifying the Coast Guard for this responsibility. He concluded his presentation by saying that air-sea rescue was a most proper and normal function of the Coast Guard. This proposal was strongly endorsed by the Navy and just as strongly opposed by the Army Air Force. A sub-committee, set up to evaluate the proposal, concluded that the Coast Guard would face insurmountable obstacles if it were to attempt to expand into all types of rescue activity for all military forces. It did, however, recommend a joint service Air-Sea Rescue Agency, headed by the Commandant of the Coast Guard, be established to analyze technical data, develop and design air-sea rescue equipment and procedures and to disseminate information to all parties engaged in search and rescue activities. It further stated that each service should retain responsibility for its own aircrews.

The Navy chose to utilize Coast Guard assets and expertise. Plans were developed whereby the Navy would provide air-sea rescue units for the Pacific operations and the Coast Guard would assume all rescue activities within the Continental Sea Frontiers and on all overseas airways. It also suggested that the Coast Guard, based on its communication system and past experience, handle all radio direction finding and the navigational aids along the airways now serviced by the Army Airways Communications System (AACS). No official reaction was forthcoming from the Army Air Force with the exception that on the principle routes of the Army Air Force, AACS would continue to handle all communications and navigational aids as a matter of primary interest. During the summer of 1944 Major General Laurence S. Kruter proposed that ASR become an integral part of the Army Air Force Organization and to become part of the Air Transport Command.

The Navy pressed ahead and assigned ASR responsibility to the Sea Frontiers and designated the Coast Guard to man and operate ASR facilities for the

Sea Frontiers. The combination of aircraft, ships, shore stations and communication facilities were developed into a highly efficient operation. The Navy position was enhanced when in March 1945 General George, ATC commander, officially expressed concerns over the assignment of responsibility to ATC for rescue coverage on transportation routes. As part of his conclusion disagreed with by many within the Army Air Force, he wrote that when the magnitude of the operation for emergency rescues at sea is realized, that a conclusion is reached that the only way to provide the maximum rescue capability is by turning this responsibility over to the Navy.

The CNO in a letter outlining policy, serial number 3744 (25 April 1945), stated that the responsibility for Air-Sea Rescue as assigned to Frontier commanders would terminate at the end of the war and that post war ASR would be a function of the Coast Guard. It directed that a detailed study of facilities and equipment be made for the purpose of turning over to the Coast Guard that which would be required. LT Gen Hoyt Vandenberg, USAAF, recognizing that the coverage of the transport routes by the AAF had been neither efficient nor economical, proposed that the AAF provide global coverage with rescue squadrons assigned to the various Air Forces throughout the world to adequately provide for potential combat needs. In recognition of the merit in the Navy’s proposal, the Coast Guard would be responsible for a comprehensive sea rescue program for transoceanic air routes and the maritime regions of the United States and its possession. In addition, an AAF land–air search and rescue organization would be established for the interior areas of the United States and liaison would be maintained with the Coast Guard. In the late fall of 1945, the Navy began to deactivate its own rescue units and pressed for the Coast Guard to take over responsibility for ASR. On 4 December the Commandant of the Coast Guard informed the Navy that the Coast Guard accepted in principle the responsibility for Air Sea Rescue.

There were those within the Coast Guard that had serious reservations. During 1944 a comprehensive description of the functions the Coast Guard expected to perform in peacetime had been drawn up. The result would be an expansion of pre-war activities but a dramatic reduction in the size of the Coast Guard from the wartime level. It was felt by some that an Air-Sea Rescue responsibility of the size envisioned would expand one branch of the Service to the detriment of the others. It was further feared by some that the full implementation might result in a degree of Navy jurisdiction in Coast Guard operations. ADM Waesche, who was ill, retired effective 1 January 1946, the date the Coast Guard was returned to the Treasury Department. As a result, the Coast Guard lost its most effective advocate for the expansion of Coast Guard rescue duties. A series of events took place, however, that established a logical transition into a much greater role in search and rescue operations on the part of the Coast Guard.

Fifty-two allied and neutral states had met in November of 1944 and an interim agreement was reached for a Provisional International Civil Aviation Organization (PICAO), with headquarters in Canada, to become effective 6 June 1945. Regional meetings were held dealing with the various technical subjects of concern to civil aviation such as Aerodromes, Air Routes, and Ground Aids; Air Traffic Control; Communications; Air Navigation Aids; Meteorology; and Search and Rescue. Although it was not readily apparent in the early stages of the PICAO that the Coast Guard would become involved to any great extent, it was noted that at least two and possibly three of the technical subjects under discussion involved items in which the Coast Guard had an interest. The Montreal divisional meeting in the fall of 1945 was concerned with the development of a search and rescue program. LT John M. Waters attended as the Coast Guard aviation representative. The meeting developed certain search and rescue terminology, the conditions under which search and rescue action was taken; and outlined requirements for the establishment of Rescue Coordination Centers and specially equipped rescue units. The work which the representatives performed in this meeting was important as it established a firm foundation upon which the future organization of international search and rescue would be built.

The Coast Guard had developed and was operating the LORAN navigation system. This too would affect future operations. This system was in use by both aviation and marine transportation. PICAO policy was that the LORAN, along with certain other aids, should remain in operation until a final determination of a standardized long range air navigation system evolved. Upon final determination, LORAN became the standard navigational system and remained a Coast Guard operation.

As a result of these duties and previous experience, the Coast Guard was designated as the coordinating agency for Search and Rescue operation and the agency with primary responsibility for providing Search and Rescue facilities and services to meet United States obligations to PICAO. This was in addition to Coast Guard responsibility for search and rescue operations upon and above the maritime waters and adjacent areas of the United States and its Territories. On 3 September the Air-Sea Rescue Agency, in recognition of expanded responsibilities, was renamed the Search and Rescue Agency and Search and Rescue (SAR) became the descriptive name of choice.

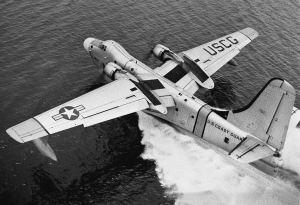

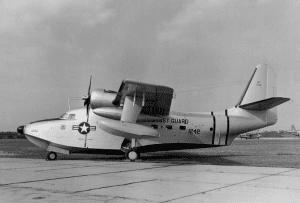

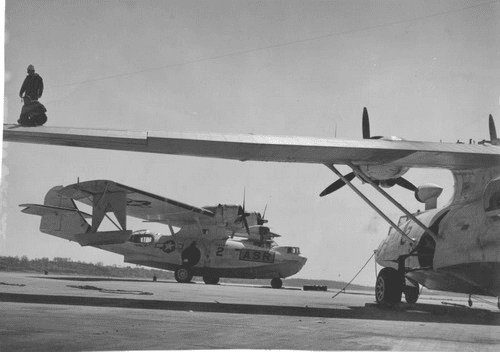

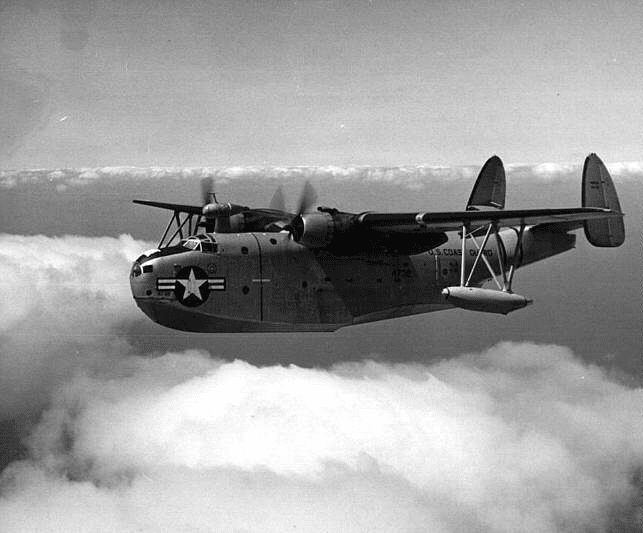

When the Coast Guard transferred back to the jurisdiction of the Treasury Department nine Coast Guard air stations plus the detachments at Annette Island Alaska and the detachment at Kaneohe Bay were returned to Coast Guard operational control. Additional air detachments were established at Traverse City, Michigan and Sangley Point in the Philippine Islands during 1946. A detachment was also established as part of the joint North Atlantic Ocean Patrol (NORLANTPAT) at the Naval Air Station Argentia, Newfoundland. The function of the patrol was to maintain up to 11 Ocean Station Vessels, the North Atlantic LORAN chain, and provide rescue services for the area. In 1947 air detachments were established at Kodiak, Alaska; Guam and San Juan, Puerto Rico. NORLANTPAC was discontinued and the air detachment at Argentia remained as a Coast Guard air detachment. The PB-1G went operational in 1946 and P4Y-2 long range search aircraft were on board replacing a number of the PBYs. PBM-5s were also obtained and replaced the PBM-3s and some of the PBYs. The Coast Guard, in 1947, was operating four ocean stations in the Atlantic and two in the Pacific. A realignment of LORAN was taking place to better serve the needs of the present military and civilian requirements.

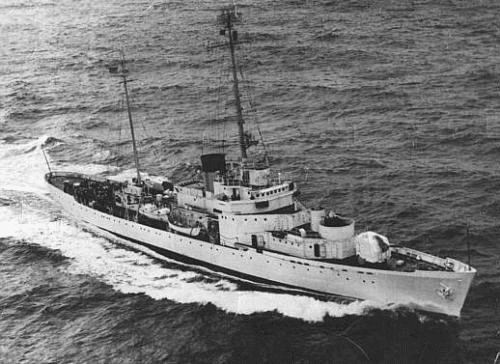

Ocean station vessels played an important part. In addition to weather information, they provided positive locations of aircraft transiting the oceans. An inbound aircraft would be picked up on the ship’s radar and tracked for a period as it passed over and beyond the ship. This provided highly reliable track and speed information for the aircraft. The vessels also were available to assist if ditching became a necessity. No ditching is safe but they are a lot safer if the aircraft can ditch alongside a vessel with rescue capabilities.

In 1947 ICAO members ratified a treaty establishing Ocean Stations, the cost of which to be prorated among the member nations. The United States agreed to accept responsibility for seven stations. Full establishment of all stations was expedited by an event on the night of 13-14 October of that year. One of the Boeing 314 clippers, a flying boat named Bermuda Sky Queen, en route from England to the United States, encountered 100 mile-an-hour headwinds after passing the point of no return. Unable to make the North American coast and unable to get back to Europe, the pilot elected to fly back to and make a controlled ditching alongside the Coast Guard cutter Bibb at Ocean Station Charlie. The landing would not be routine. A moderate gale had been blowing and a confused sea was running. The pilot put the plane down with 62 passengers and seven crew members sustaining very little damage. Getting the passengers transferred to small boats and then to the Bibb was challenging but accomplished. All passengers and crew were rescued without loss. The story became headline news and solidified the establishment of the ocean stations. There were a number of additional controlled ditchings carried out; all were successful.

A reduction of personnel and obtaining sufficient funding were serious problems faced by the Coast Guard as a whole after the war. ADM Joseph Farley had become Commandant of the Coast Guard and the task confronting him was gargantuan. He oversaw the Coast Guard’s demobilization and supervised the renewal of traditional peacetime activities without neglecting the duties that had accrued to the service during the war. By mid 1947 the Coast Guard reached a nadir of 2,195 officers, 532 warrant officers, and 15,730 enlisted men, little more than half the number thought necessary to carry out the post war program drawn up by ADM Waesche’s planners. Several senior officers later asserted that the Coast Guard would have fared better during the immediate postwar years had it remained under the Navy Department for a longer period of time, principally because neither the Treasury department nor congressional committees responsible for Coast Guard support after the war had any recent knowledge of the Coast Guard’s expanded role and attendant requirements. By early 1948 the number of operational aircraft had been reduced from 195 to 71. Nevertheless, the Coast Guard continued to perform the search and rescue mission very well.

Extensive evaluation of methods, procedures, and techniques used to land seaplanes in rough water were conducted by the Coast Guard under the direction of the then CDR. D.B. MacDiarimid beginning in 1945. Largely as a result of this work, seaplane rough water landings in the open sea became safer – not safe – but safer. The results were also used successfully in training aircrews, both military and civil, for ditching at sea. The Coast Guard initiated and carried out a program to indoctrinate commercial and military flight crews in correct emergency procedures. An understanding of swell and wave action by a pilot ditching is essential. Following closely in importance to the pilot placing the aircraft on the water properly, correct evacuation procedures are crucial. Crew members must be able to get life rafts and associated equipment into the water promptly. To safely evacuate persons on board, fast and effective action is necessary. Training was conducted at principal Coast Guard air stations. Mockups were employed with good success. At San Francisco where the crews of many airlines flying the Pacific, both US and foreign, received training, the fuselage of a four engine plane was moored half submerged in San Francisco Bay. After preliminary training crews were placed aboard the mock-ups and exercised in abandoning the mock-up and getting survival equipment into the water. Most trainees were afforded the opportunity to participate in an exercise with a large cutter. They would depart a smaller vessel rigged with a mock-up hatch and wing section and upon signal the trainees would abandon the mock-up in life rafts which they themselves inflated. In a heaving sea, this was an illuminating experience.

The initial concept of air-sea rescue was geared to the survival and rescue of the crews of aircraft who, for whatever reason, were in peril due to the loss of their aircraft. Two approaches were advanced. The Army Air Force (AAF) approach was to analyze the frequency and concentration of aircraft traversing a given area. This was known as route coverage. Facilities were the responsibility of the command and were placed to reach a given location in the shortest period of time. The approach used by the Navy was area coverage in which facilities were placed so as to provide a blanketing effect on the entire region. The potential drawback here is that the number of facilities is determined by equipment availability. When the Coast Guard was charged with air-sea rescue responsibilities for the Sea Frontiers they integrated both approaches into a very effective network. Vessels such as 110 foot PCs, 125ft, and 165ft cutters were factored into the equation. In addition to the AVR boats at the air stations, they drew upon a series of life boat stations, all equipped with small boats, up and down the coasts. Further, they fully utilized an excellent landline and radio communication system.

Coordination was a key part of the equation. It was recognized that it would be impossible, from an economical standpoint, to establish adequate facilities for the exclusive use of search and rescue. However, other assets already in existence for other purposes can frequently be utilized to great advantage. Arrangements were made to monitor merchant vessel position reports and liaison was maintained with various HF/DF radio facilities. Additional liaison was maintained with Federal, State, and Municipal agencies capable of rendering assistance. The matter of establishing a working plan and providing for the supervision of available facilities best describes what is meant by coordination. Rescue Coordination Centers were established for this purpose. Commandant Coast Guard Circular 13-44 dated 1 April 1946 established four Coast Guard Area Commands, to act as Task Force Organizations under the Commandant. The Task Forces functions, analogous to the naval Sea Frontiers, maintained joint operation control centers. The Task Forces were composed of the Coast Guard Districts within their respective areas. The Eastern Area command had the added responsibility of the North Atlantic Ocean Patrol. The number of Task Forces was later consolidated into Eastern Area and a Western Area commands.

This concept is illustrated by an incident involving a twin engine Navy patrol bomber that departed from an overseas base for Norfolk. Disaster does not always arrive all at once. It may start as a minor difficulty that is soon compounded by others. Shortly after takeoff, the LORAN, an electronic device for determining the position of the aircraft, was found to be inoperative. The flight entered clouds prohibiting taking a sun line by sextant or obtaining a drift reading from the sea below. But with only several hours remaining before reaching Norfolk, the flight continued and the navigator computed his assumed position from course and speed flown. The aircraft was on autopilot and a steady course of 295 degrees was flown. Late in the afternoon, the aircraft broke out of the clouds and the pilots realized that the sun was not setting in the position it should have been. Disengaging the auto pilot the aircraft was turned toward the sun. The compass card did not move. The compass was stuck and it was not known how long it had been in that condition. They did not know where they were!

They promptly reported the circumstances to New York Overseas Radio who in turn reported it directly to the Coast Guard’s New York Rescue Coordination Center, known by voice call as “Atlantic Rescue.” Atlantic Rescue assumed control and an alert went out by high speed teletype to the various rescue commands along the Atlantic coast. This included the Net Control Station of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in Washington. The FCC had high frequency direction finding stations (HF/DF) and the first priority was to locate the lost aircraft. Bearings from several HF/DF stations were obtained from the patrol bomber and plotted on a chart establishing the position of the lost aircraft. Instead of being 550 miles to the west of Bermuda the aircraft position was 420 miles northeast of Bermuda. Bermuda was the closest landing point and it was suggested that the aircraft take steers for Bermuda. Bermuda DF gave a steer of 205 degrees magnetic. Bad weather was not a novelty to Bermuda but fog was a rarity. A thick fog was settling in with low ceilings and less than a quarter of a mile visibility. The island had no precision instrument approach and due to the hills in the area the minimum ceiling allowed for aircraft instrument approaches was 700 feet. Bermuda was below minimums but it was the only place that could be reached with the fuel remaining. When the lost aircraft reported that it was marginal as to whether there would be enough fuel to reach the island a PBM-5 was scrambled from the Bermuda Coast Guard Air Detachment for intercept and escort of the inbound aircraft. Fog was thick and radar was used to reach the sealane for takeoff. In addition, the Coast Guard cutter Cook Inlet, the standby rescue vessel at Bermuda, was ordered to proceed to assist.

The PBM-5 homed in on the inbound distress aircraft using VHF/DF and commenced escort. Fuel was re-evaluated and it was thought to be enough to reach Bermuda. The Cook Inlet proceeded to a point five miles off the end of the runway, turned on her radio beacon and was ready to provide radar service and talk the navy pilot down. The weather was reported as 200 ft and visibility one-half mile. It was not an approved approach but there was little choice. If the approach failed then a night ditching – an extreme measure- would have to be made. The pilot of the Navy plane was thoroughly briefed on the procedure to be used. It was explained that on final approach Cook Inlet would call out the distance to the island every one-half mile. If the runway was not sighted at one mile an immediate pull up to the left would be executed and preparations for a ditching would be initiated.

Communications were established between the Navy aircraft and the Cook Inlet and as he arrived over the ship he let down to 1000 feet and executed a procedure turn ten miles out and proceeded inbound for final approach. As he passed over the ship and homed in on the Kindley AFB radio beacon, Cook Inlet was transmitting a steady flow of information. He was on course and distance was provided. He established a rate of decent to arrive over the end of the runway at 200 feet. As he neared the runway Cook Inlet transmitted standby to mark one mile. At Mark one mile— “Pull up” – was transmitted. The response from the pilot was – “Runway in sight” and the aircraft landed safely. The PBM made an approach to the Naval Station seadrome on its own radar and the Cook Inlet returned to its moorings at St. George.

Intercept and escort of lost aircraft as well as those experiencing a loss of an engine became a regular part of search and rescue (SAR) activities. Accuracy in aerial navigation was a relative thing. Over the United States and Canada, with the vast electronic navigation system, a professional pilot on an instrument flight plan called his fixes down to the minute. But over many vast stretches of ocean, navigation aids were few and the aircraft could be 50 miles in error in its position without seriously affecting the flight. As it approached its destination and picked up shore based aids the position became increasingly accurate. It is difficult to locate survivors in the water. The greater the uncertainty of the location of survivors the greater the possibility they will not be located. The loss of an engine affected the range and endurance of an aircraft. Even four engine aircraft were affected by the loss of an engine. The loss of two became a very serious matter. The intercept and escort of an aircraft provided a positive fix in case of a ditching. In some cases, if the escort was a seaplane and a landing could be made it was, but in all cases additional life rafts and survival equipment could be provided and surface vessels could be directed to the location of the survivors. In the years to come, aircrew training, the ocean station program and aircraft escort were phased out as the jet aircraft came on the scene. The jet was faster, more dependable, had greater range and navigation aids improved dramatically. The services provided the early trans-ocean operation were no longer needed.

Many an hour was spent searching for overdue recreational boats and/or commercial fishing vessels. Many ships and vessels were saved by cutters arriving with additional pumps. Soon after World War II some unrecognized Coast Guard genius came up with the idea of a small portable pump which could be delivered rapidly by air and parachuted to a sinking vessel. A pump, capable of pumping over 60 gallons of water a minute, was packed in a water tight container complete with suction and discharge hoses and a can of fuel. They proved to be immediately successful. A retrieving line and parachute were attached to the container. The retrieving line was strung out and the pump was dropped from a low but sufficient altitude in such a manner that a portion of the retrieving line came to rest upon the vessel.

The decade beginning in 1945 was the age of the seaplane in Coast Guard aviation. In addition to landings in the open sea to pick up survivors, medical evacuations became a regular occurrence. Large seaplanes from San Diego would fly down the Baja to remove injured seamen from charters and tuna boats. San Francisco was kept busy. East Coast and Gulf aircraft would fly far out to sea to make emergency pickups. It was a dangerous undertaking and accidents did occur and aircraft were lost. Ira McMullan landed 500 miles off San Francisco, had his elevator torn off and the fuselage broke in two. Harry Solberg landed off Bermuda and the bow gave way. He escaped underwater after the crew had evacuated. Andy Couples landed to pick up a sick sailor from a submarine and both engines tore loose from their mounts. John Vuckic landed in 12-foot seas close to the Red China Coast to rescue the crew of a P2V that had been shot down by Communist anti-aircraft fire. On take off, after the JATO had been fired, one engine failed and they crashed. Four Navy and Five Coast Guardsmen were lost.

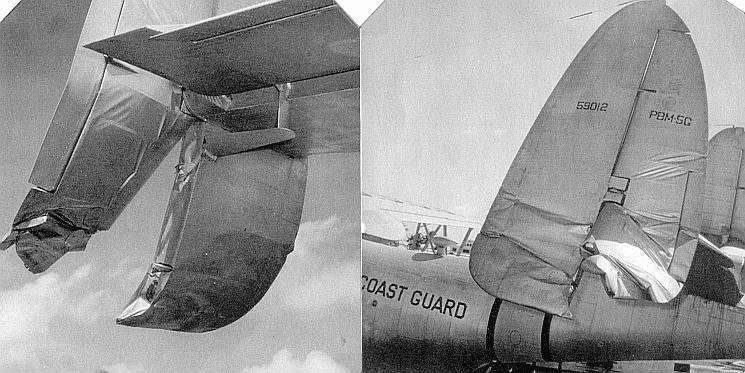

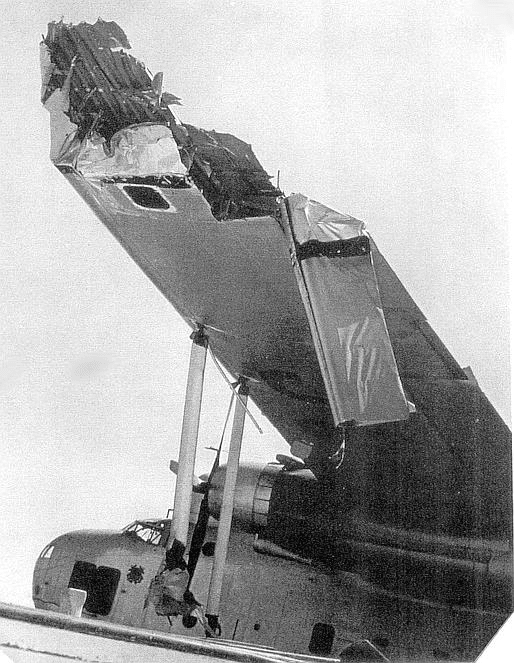

The above three pictures show damage incurred by a PBM-5 during an off-shore landing.

The continued loss of seaplanes triggered a reaction from Headquarters. It was directed that before landing in the open sea the pilot would have to obtain permission from the District Commander. This was to allow his staff to make a current check on the necessity for a landing and the availability of other means, such as surface vessels, to perform the SAR operation more safely. In theory it was a good step but in practice there were shortcomings. Primary was that the authority of the on scene commander had been usurped – in some cases by those with limited knowledge of aircraft capabilities – which is very poor SAR practice. The aviators chaffed under the restrictions and let their feeling be known but change did not result. The situation was brought to a head when a Navy P2V ditched in the Atlantic. The survivors were promptly located and the pilot, reporting favorable sea conditions, requested permission to land and pick them up. In the RCC, the plot showed a cutter 40 miles away. The survivors were in a raft and the duty officer decided the ship would make the pick up and refused to grant permission to the pilot to land. The Navy people ashore were monitoring the situation and became very upset with the decision. They called the Air Force and asked them to make the pick up. An Air Force SA-16 soon arrived, landed and picked up the P2V crew and returned them to the Navy base. Word of the “forbidden landing” quickly spread and loud protests arose from within the aviation establishment.

The Commandant modified the directive to give pilots the right to land without permission when, in their opinion, it was necessary to save life. But it was understood the decision put the burden on the pilot. If the aircraft was damaged, the pilot had best be sure the landing could be shown to be really necessary. There was more to it. Compensation and liability were not commensurate. For a number of years medals or awards were refused for even the most difficult jobs. Theories as to why they were refused were advanced but no official explanation was ever given. The fact was, however, that the policy was deliberate, arbitrary, and ill-considered. The pilots fully understood the danger in landing in the open sea but nevertheless many risked their lives and reputations to save others during those years and never received so much as an official thank you message. Fortunately, this situation has been corrected.

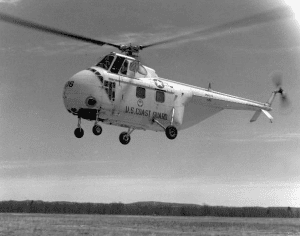

By 1951 the performance of the helicopter had been greatly improved and it was becoming an integral part of the SAR picture. The HO4S could pick up multiple people close in to shore that in former years would have required a seaplane’s help. As the range of the helicopter increased, seaplane landings became even less frequent. Moreover the helicopter could hoist people from vessels at sea or from the water in sea conditions that the seaplane could not operate in. The helicopter also proved to be an ideal vehicle for flood and hurricane relief. The P5M Mariner aircraft, designed for rough water operation were obtained in the mid-fifties but proved very costly to operate. They were retired from service a short while later leaving only the amphibious HU-16. The helicopter soon became predominant.