The Coast Guard was transferred from the Navy back to the Treasury Department on 28 August 1919. Coast Guard Captain Stanley V. Parker who had been the Commanding Officer of the Naval Air station Rockaway, New York was ordered to Headquarters and assigned as the Aide for Aviation. With the war over Parker turned Coast Guard attention back to the utilization of aircraft in the saving of life and property along the coastal regions of the United States and at sea contiguous to them. The new Commandant, William Edward Reynolds, was favorably disposed toward the establishment of a Coast Guard air station to thoroughly evaluate the concept. The authority to establish Coast Guard air stations was contained in the Navy Deficiency Act of 1916. In spite of the shortage of Officers in the Coast Guard Captain William P. Wishar, 1st Lieutenant Carl C von Paulsen, and 1st Lieutenant Edward P. Palmer were assigned to the first post-war Navy flight class at Pensacola. Palmer was found to have an eye defect which disqualified him from flight training but he continued on in aviation engineering training. Parker, qualified in both fixed wing and dirigibles, as he recognized the possibility that both types of aircraft might be advantageous in Coast Guard operations. When Wishar and von Paulsen completed fixed wing seaplane training in May of 1920 and received their Naval Aviator designation, they remained at Pensacola to take lighter-than-air training.

On March 30, 1920, Headquarters initiated a sequential listing of Coast Guard aviators. The initial listing was made up of Coast Guard Officers assigned to flight duty at the time. Stone was designated Coast Guard Aviator #1, Donohue was designated #2, Thrun became #3, Sugden was reassigned to aviation duty in April and became #4. When Wishar and Von Paulsen completed flight training they were designated Coast Guard Aviators #5 and #6. At this point designation numbers were given to all other Coast Guard officers who held naval designations. Thus Parker, Coffin, and Eaton became Coast Guard Aviators #7,#8,and #9. No more designations were issued until enlisted pilots Walter Anderson and Leonard Melka, from the original class of 1916, were commissioned. They were designated #10 and #11.

On 5 June 1920, the military ranks prescribed for the Navy became effective for the Coast Guard thereby eliminating a great deal of confusion. Coast Guard Captains became Lieutenant Commanders, 1st Lieutenants became Lieutenants, 2nd Lieutenants became Lieutenant (junior grade), and 3rd Lieutenants became Ensigns.

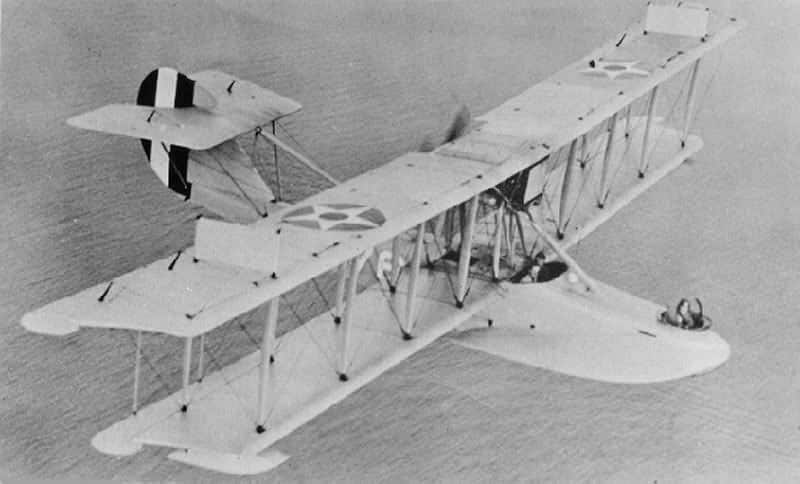

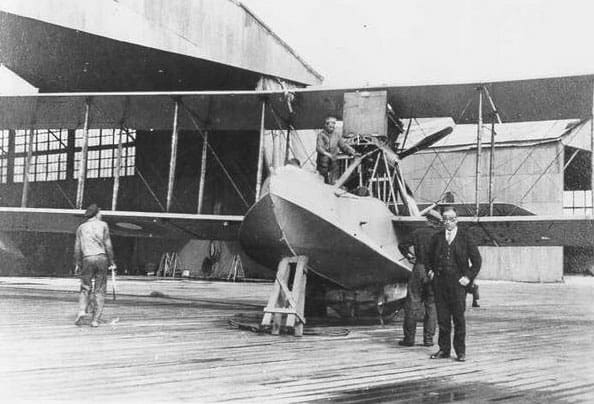

Inquiries were made to the Navy as to the availability of surplus aircraft and naval installations that could be used for the establishment of a Coast Guard Air Station. The Coast Guard was given the choice of two locations. One was at Key West, Florida and the other at Morehead City, North Carolina. LCDR Parker informed LCDR Wishar that he would be assigned as the Commanding Officer of the Coast Guard’s first air station upon completion of the lighter-than-air training and he requested his views on the most desirable location. Wishar recommended Morehead City as “best suited to prove the worth of Coast Guard aviation. It was closer to the Graveyard of the Atlantic at Cape Hatteras, where there would be more opportunities to locate vessels in distress, derelict menaces to navigation, and vessels ashore on Diamond Shoals, Lookout Shoals, and Frying Pan Shoals.” Parker informed the Navy that the Coast Guard had chosen Morehead City. The request for aircraft was also honored and four HS-2L Curtiss flying boats and two Aeromarine Model 40s were provided.

Inquiries were made to the Navy as to the availability of surplus aircraft and naval installations that could be used for the establishment of a Coast Guard Air Station. The Coast Guard was given the choice of two locations. One was at Key West, Florida and the other at Morehead City, North Carolina. LCDR Parker informed LCDR Wishar that he would be assigned as the Commanding Officer of the Coast Guard’s first air station upon completion of the lighter-than-air training and he requested his views on the most desirable location. Wishar recommended Morehead City as “best suited to prove the worth of Coast Guard aviation. It was closer to the Graveyard of the Atlantic at Cape Hatteras, where there would be more opportunities to locate vessels in distress, derelict menaces to navigation, and vessels ashore on Diamond Shoals, Lookout Shoals, and Frying Pan Shoals.” Parker informed the Navy that the Coast Guard had chosen Morehead City. The request for aircraft was also honored and four HS-2L Curtiss flying boats and two Aeromarine Model 40s were provided.

LCDR Sugden, Parkers Executive Officer at the Rockaway Naval Air Station, was assigned temporary duty as Commanding Officer during the period the Morehead City Air Station was being outfitted. LCDR Stone was given the responsibility of supervising the reconditioning and testing of the HS-2L flying boats that were to be used by the station. In November, the Navy requested Stone’s services in connection with aircraft catapult tests and development. Headquarters approved the request and Stone reported to the Aircraft division of the Navy Bureau of Construction and Repair on 20 November 1920, for duty. LCDR Wishar reported in to Morehead City in January 1921 and relieved Sugden. Von Paulsen reported in about the same time. The others assigned were LCDR Robert Donohue, Executive Officer; LT Edward Palmer, Engineering Officer; Gunner C.T. Thrun, Pilot; Machinists W.S. Anderson, Assistant Engineer and Pilot, Carpenter Theodore Tobiason, in charge of aircraft work: Chief Petty Officer Leonard Melka, Pilot; and 16 additional enlisted personnel to maintain the aircraft.

LCDR Wishar described the HS-2L as follows: “It was a heavy plane; single engine (Liberty), pusher-type, open cockpit. It was

staunchly built, could land in a fairly heavy sea when emergency demanded, and could take off in a moderate sea. It took off at a speed of 48 knots and flew at 55 knots, a leeway of 7 knots between flying speed and stalling speed. If she stalled, she went into a spin. No flyer that I’ve heard of ever pulled a fully manned and equipped HS-2L out of a spin. Everyone that spun crashed, killing all on board. It had to be constantly “flown” while in the air. It carried a pilot, co-pilot, and in the bomber’s seat in the bow a combination observer and radio man. It was tiring to fly: constant pressure had to be maintained on the rudder-bar because of torque of the single propeller. I’ve come in from many a flight, and, upon landing, my right instep would be so painful it was difficult to walk.

To prevent this, the Navy developed a heavy rubber cord attached to the left end of the rudder bar, thence to the rear for about three feet where the end was secured. It was adjusted to equal the pressure needed on the other side of the rudder bar, while flying, to keep the plane straight. It was called a “Bungee.” In a way, it was dangerous because, when the engine was cut for a landing glide, prop torque ceased, the bungee caused left rudder, the plane turned without banking, was difficult to control, and would tend to go into a spin. The pilot had to remember this and press against the bungee’s pull on the rudder when he had cut his engine. Some pilots forgot. They never had a chance to forget again.”

LT Robert Donohue was an exception and believed an H boat could be brought out of spin. He stripped a HS-2L of all removable gear and took off with a light fuel load and only himself in the airplane. No preparations had been made for rescue in case of a crash because LCDR Wishar was not aware of what was intended. Wishar first found out as Donohue started his climb out and hastily prepared for what he thought was a certainty. Upon reaching 3500 feet Donohue put the aircraft into a spin and made four complete turns, then smoothly brought the aircraft out of the spin and landed just off the station. He had proved a HS-2L flying boat could be brought out of spin. Wishar said it was either a courts-martial for risking the plane and his life or a recommendation for a medal for bravery beyond the call of duty. It must have been the latter because Donohue retired as a Rear Admiral.

Upon establishment of the air station a Headquarters directed assigned duties and responsibilities in order of priority:

- Saving life in coastal regions and adjacent waters

- Saving property in coastal and adjacent waters.

- Enforcement of laws and assisting federal and state officials engaged therein.

- Transportation of officials to remote areas if time precluded the use other means.

- Assisting fishermen by spotting schools of fish.

- Surveying and mapping.

The HS-2L fell far short of the aircraft that would follow. Range was a limitation and as a result gasoline and oil were stored in drums at strategic locations in the operating area. Engine failures happened regularly. Wishar stated that he had three while the air station was in operation. Space to carry a rescued or ill person was very limited. But the ability to patrol and fly from bays and inlets and in some cases the open seas was demonstrated. In a summary of activities, Commodore W.E. Reynolds, the Commandant of the Coast Guard reported to the Secretary of the Treasury that:

“The application of aviation to the uses of the Coast Guard in the direction of saving life and property from the perils of the sea, in locating floating derelicts along our coasts, and rendering other kindred services, can now be regarded as an assured proposition. A Coast Guard aviation station has been established at Morehead City, N.C. at practically no expense to the government. The aircraft in use are the Navy H-S flying boats and the station is conducting experiments with the view of furthering the effectiveness of aircraft to life and property saving purposes. It is earnestly recommended that the Congress give its support to the development of this activity for Coast Guard purposes.”

The air station continued to prove its worth but there was no appropriation for continued operation forthcoming from Congress. The Morehead City air station remained in commission until July, 1922 at which time personnel were transferred to other assignments and the aircraft were returned to the Navy. There would be no more Coast Guard aviation activity until the advent of the Coast Guard Air Station at Gloucester Massachusetts in 1926. Only five out eleven of the initial cadre returned to flight status.

With the closing of the Morehead City air station morale was low in the aviation community but another misfortune had affected the morale of the entire officer corps. During World War I and the immediate post war years while still a part of the Navy, Coast Guard officers had received temporary promotions commensurate to their assignments and responsibilities. The Captain Commandant was promoted to the Rank of Commodore USN and others had been promoted to Captain, Commanders and Lieutenant Commanders. They fit well within the Navy rank structure but when the Coast Guard reverted to its pre-war rank structure the rank distribution was exceedingly top heavy. For example there were 154 Coast Guard Officers holding the rank of Lieutenant Commander out of a total authorized strength of 268 officers. On 17 October, 1921, all Coast Guard officers reverted to their permanent rank. The Navy rank terminology was retained but all but 36 of the Lieutenant Commanders reverted to Lieutenant or Lieutenant (junior grade). Obviously the large reduction in rank had a detrimental effect on the procurement of new officers. There were vacancies in the grade of Ensign for 65 officers.

The situation was improved when the “Act to distribute the commissioned line and engineering officers of the Coast Guard in grades, and for other purposes” was enacted in January of 1923. The title of the Captain Commandant was changed to Commandant with a rank of Rear Admiral (lower half) and authorized the promotion of 11 senior officers to the rank of Captain. Maximum numbers for lower ranks were adjusted accordingly. Most importantly, a provision was made for promotions at regular intervals and the adjustments made at regular intervals. Maximum numbers in grade would also to be adjusted to changes in the authorized number of Coast Guard officers and pay and allowances were that of naval officers. This gave the young Coast Guard officer about the same opportunity for promotion as his opposite number in the Navy and did much to improve the morale in the officer corps.