LT(jg) R.G. Thomas who was in charge of the Navy Hydrographic Office in Norfolk Virginia, like a number of others, had become interested in the flight tests being conducted in conjunction with the Coast Guard Cutter Onondaga. Based on test result and an awareness of the Coast Guard coming need for pilots to continue evaluation flights, Thomas, apparently on his own initiative, sent a letter to the Navy Department via the Hydrographer in Washington, DC informing the Department of this situation. The Secretary of the Navy in his letter of March 21, 1916 replied as follows:

To: Lieut. (jg) R.G. Thomas, U.S.N. Branch Hydrographic Office, Norfolk, Va.,

Via: Hydrographer

Subject: Training in aviation for officers of the Coast Guard Service

1. It is gathered from your letter that you are in touch with officers of the Coast Guard Service who contemplate taking training in aviation. You are authorized to inform such officer or officers that if the Captain-Commandant of the Coast Guard Service will make a request on the Navy Department for the opportunity for the training of his officers, the Department will be very glad to add two Coast Guard Officers to the class at Pensacola.

2. A new class will be formed April 1st, and it would be advantages if these requests should be received in time for the officers to take up the course on that date.

Joseph Daniel s/s

Response was rapid. Lt(jg) Thomas forwarded Secretary of the Navy Daniel’s letter on March 23rd and on the same day it was on the way to Coast Guard Headquarters with Captain Chiswell’s endorsement which read in part:

“If Lieut. Stone could be detailed to the Navy Aviation School at Pensacola in this class to be formed April 1st; he could in a short time period obtain a pilot’s license and be grounded for taking up the work outlined in Captain Baldwin’s offer. I believe it would not be many months before we might be able to conduct some very interesting and valuable experiments here without cost to the Government.”

B.M. Chiswell s/s

Captain USCGThe Acting Secretary of the Treasury submitted the following request to the Secretary of the Navy on March 25th.

Sir:

I have the honor to request that an opportunity be affected this department to have two officers of the Coast Guard receive flight training in aviation at Pensacola in the class which, it is understood, will be formed on April 1, 1916.

In the event of favorable consideration of the foregoing, I would request that you furnish this department with several copies of the circular relating to the physical requirements of officers detailed to aviation duty.

Respectfully,

Byron R. Newton s/s

Acting Secretary

On 1 April 1916, 3rd Lieutenant Elmer F. Stone, followed by 2nd Lieutenant Charles E. Sugden, reported to the US Navy Aeronautic Station, Pensacola, Florida for assignment to naval flight training. In October 2nd Lieutenant Norman B. Hall was ordered to the Curtiss Aircraft Company to study aircraft engineering and construction. The rapidity with which this series of events took place is very unusual.

The official beginning of Naval Aviation was May 8, 1911 when Captain Washington I. Chambers USN, who had been designated as Officer in Charge of Aviation, issued requisitions for two Curtiss biplanes. The Navy Department had been awakened to the potential of the aircraft in naval operations during the previous year. Eugene Ely had flown a Curtiss biplane from a specially built platform on the cruiser Birmingham on November 14, 1910. Two months later, January 18, 1911 he landed a Curtiss pusher aboard the cruiser Pennsylvania. A few weeks later the seaplane made its appearance. The first three Naval Aviators were given instruction at the Curtiss installation. This was followed by a camp established at Groonsbury Point near Annapolis, Maryland, and initial naval flight operations began.

In October 1913, the Secretary of the Navy, Joseph Daniels appointed a board, with Captain Chambers designated as chairman, to make a survey of aeronautical needs and establish policies for future development. One of the board’s most important recommendations was the establishment of an aviation training station. This was approved and the site selected was on an abandoned Navy yard at Pensacola, Florida. The first U.S. Naval Air Station was created in 1914 and Commander H.C Mustin became the first Commanding Officer. All aircraft and pilots were ordered there for duty. A row of 10 tent hangars was set up along the beach with wooden ramps running from the tent to the water. This is how Lieutenants Stone and Sudgen found it when they reported to flight training in 1916.

In October 1913, the Secretary of the Navy, Joseph Daniels appointed a board, with Captain Chambers designated as chairman, to make a survey of aeronautical needs and establish policies for future development. One of the board’s most important recommendations was the establishment of an aviation training station. This was approved and the site selected was on an abandoned Navy yard at Pensacola, Florida. The first U.S. Naval Air Station was created in 1914 and Commander H.C Mustin became the first Commanding Officer. All aircraft and pilots were ordered there for duty. A row of 10 tent hangars was set up along the beach with wooden ramps running from the tent to the water. This is how Lieutenants Stone and Sudgen found it when they reported to flight training in 1916.

The initial aircraft used for flight training was a Curtiss AH-9 seaplane with bamboo outriggers. The AH-9

was a “pusher type” meaning the engine was mounted with the propeller facing aft thus propelling the aircraft forward as a reaction to the air being “pushed” aft. This provided excellent forward vision for the pilot. The aircraft proved dangerous however because the engine mounting was weak and if the aircraft crashed the engine would fall forward crushing the pilot. CDR Mustin asked that the aircraft be replaced but with no immediate substitute aircraft available 18 additional AH-9s were ordered by the Director of Naval Aviation. The Director did agree to order experimental “tractor” type aircraft from both

was a “pusher type” meaning the engine was mounted with the propeller facing aft thus propelling the aircraft forward as a reaction to the air being “pushed” aft. This provided excellent forward vision for the pilot. The aircraft proved dangerous however because the engine mounting was weak and if the aircraft crashed the engine would fall forward crushing the pilot. CDR Mustin asked that the aircraft be replaced but with no immediate substitute aircraft available 18 additional AH-9s were ordered by the Director of Naval Aviation. The Director did agree to order experimental “tractor” type aircraft from both

Curtiss and Martin which had the engine mounted forward and “pulled” the aircraft through the air. Several more accidents occurred killing the pilots resulting in the grounding of the AH-9s.

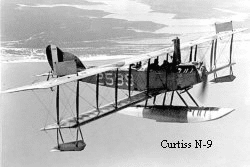

The Naval Deficiency Act of 29 August 1916 provided funds for the purchase of 30 Curtiss N-9 “tractor” seaplanes. This was an adaptation of the Army’s JN “Jenny” airplane. To make the conversion a single large pontoon was mounted below the fuselage with a small float fitted under each wing tip. These changes required a ten foot increase in wingspan to accommodate the additional weight. Further modifications to the standard “Jenny” design were required to compensate for stability problems. These included lengthening of the fuselage and increasing the area of the tail surfaces. The N-9 was originally developed with 100 HP OXX-6 engine. This was replaced with a 150HP Hispano-Suiza engine that was being manufactured under license. Of note is the fact that the Navy utilized wind tunnel data developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The N-9 was the first U.S. Naval aircraft to incorporate wind tunnel data directly into its design.

The Naval Deficiency Act of 29 August 1916 provided funds for the purchase of 30 Curtiss N-9 “tractor” seaplanes. This was an adaptation of the Army’s JN “Jenny” airplane. To make the conversion a single large pontoon was mounted below the fuselage with a small float fitted under each wing tip. These changes required a ten foot increase in wingspan to accommodate the additional weight. Further modifications to the standard “Jenny” design were required to compensate for stability problems. These included lengthening of the fuselage and increasing the area of the tail surfaces. The N-9 was originally developed with 100 HP OXX-6 engine. This was replaced with a 150HP Hispano-Suiza engine that was being manufactured under license. Of note is the fact that the Navy utilized wind tunnel data developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The N-9 was the first U.S. Naval aircraft to incorporate wind tunnel data directly into its design.

This same Act provided the means by which the Coast Guard sent an additional 15 personnel to Pensacola for flight and aviation support training. Both Stone and Sudgen upon completion of training were assigned as flight instructors.

Lieutenant Eugene Coffin, who would rise to the rank of Rear Admiral, arrived in late November of 1916 to commence flight training. He stated that; “In early April while I was still under instruction, Lieutenant Stone and I spun into the Bay from 600 feet — the first tailspin they had ever seen there. The plane was completely washed out and I had a broken nose and a split upper lip.” The method of recovery from a spin was accidentally discovered by Marine Captain Francis Evans. At altitude, out of sight of the air station, he attempted to loop the aircraft. He went into a shallow dive to gain speed but on the “pull up” he stalled out and the aircraft snapped into a spin. He realized he had stalled and that the aircraft was rotating very fast. His reaction was to nose the plane over to regain speed and when he tried to stop the rotation using his rudder, it worked! He repeated this maneuver several times picking up a little more speed on each subsequent attempt and spinning out on each occasion. Finally he was able to complete the loop. Having taught himself the technique of looping the aircraft and recovering from a spin, he decided to demonstrate the procedure in full view of all hands. Arriving back over the station he looped the airplane followed up by another loop in which he stalled the airplane. He allowed the airplane to make three turns and then made his recovery. From that time on, spin recovery became a part of the flight course. In 1936, some twenty years later, Evans was retroactively awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

War was declared on Germany on 6 April 1917 resulting in increased activity at a much more rapid pace.

From left to right:

- C.T. Thrun, Master at Arms, later a warrant officer who was killed while flying at Cape May, N.J., in January, 1935;

- J. F. Powers, Oiler First Class, who later left the service;

- George Ott, Ship’s Writer, who later left the service;

- C. Griffin, Master at Arms, who later left the service;

- John Wicks, Surfman;

- Third Lieut. Robert Donohue, who became Rear Admiral, was Chief Air-Sea Rescue Office, Chief, Personnel Office at Headquarters, retired June 1, 1946.

- Second Lieut. C. E. Sugden, who retired a Captain on August 1, 1946;

- Second Lieut. E. A. Coffin, who retired a Rear Admiral on April 1, 1950;

- First Lieut. S. V. Parker, who retired as Vice Admiral Sept. 1, 1947;

- Second Lieut. P. B. Eaton, who became Rear Admiral, and Assistant Engineer-in-Chief at Headquarters, retired August 31, 1946.

- Third Lieut. E. F. Stone, designated Coast Guard Aviator No. 1 who in 1919 made history as pilot of the Navy Seaplane NC4 that made the first trans-Atlantic crossing, was a Commander when he died May 20, 1936.

- Ora Young, Surfman, who later left the service;

- W. R. Malew, Coxswain, who later left the service;

- J. Meyers, Surfman, who later left the service;

- J. Medusky, Asst. Master at Arms, who later left the service;

- R.F. Gillis, Signalman Quartermaster

- W. S. Anderson, Surfman, who retired as a Lieut. Commander, November 1, 1946;

- L. M. Melka, Signal Quartermaster, later became a Lieutenant.