In 1911 President William H. Taft established a Commission on Economy and Efficiency under the direction of Professor Frederick A. Cleveland to recommend ways to increase the economy and efficiency of the government. The Commission determined that government agencies were more efficient and economical when unifunctional as opposed to multifunctional. A portion of this report recommended that the assets and manifold duties of the Revenue Cutter Service, some of which had never been formally assigned, be apportioned among other government agencies and departments. The commission report also recommended merging the Lighthouse Service and the Life-Saving Service due to their similar protection function. The Commission further recommended that each of the three Departments concerned; Navy, Commerce and Treasury be consulted before the bill went forward.

Secretary of the Navy George von L. Meyer said he was interested in the revenue cutters and enlisted personnel but stated that the chief functions of the Revenue Cutter Service could not be accomplished during the regular performance of Navy duties. Secretary of Commerce and Labor Charles Nagel favored combining the Lighthouse Service and the Life-Saving Service and that it be placed under his control. He further stated that he would need some of the revenue cutters for aiding ships in distress off the American coasts. The final responses came from Secretary of the Treasury Franklin MacVeagh and the Revenue Cutter Service’s Captain Commandant Ellsworth Price Bertholf. Secretary MacVeagh responded angrily. He questioned the validity of the alleged efficiencies put forth by the Commission and echoed the Navy’s argument with reference to their inability to perform Rescue Cutter Service functions. Captain-Commandant Bertholf asserted that without the revenue cutters the Departments of Commerce and Labor, Agriculture, Interior, Justice, and Treasury would have to obtain their own maritime assets in order to meet certain parts of their responsibilities which would require additional expenditures for procurement and operation resulting in increased costs and a proliferation of forces afloat.

President Taft forwarded the Commission’s report to Congress in April 1912 “recommending passage of the legislation necessary to put its various sections into effect.” Secretary MacVeagh remained opposed and directed Captain-Commandant Bertholf and Sumner Kimball, to draft legislation that would join the Revenue Cutter Service with the Life-Saving Service

Two major events took place within ten days of President Taft’s recommendation that brought the Revenue Cutter Service and the Life-Saving Service to public awareness. The liner Ontario caught fire off of Montauk Point Long Island and a joint effort of the Revenue Cutter Service and the Life-Saving Service rescued the entire crew without loss of life. Three days later the White Star liner Titanic, after hitting an iceberg, sank with a high loss of life. In response the Navy conducted ice surveillance in May of that year utilizing two light cruisers. Bertholf prepared a memorandum stating that North Atlantic ice surveillance was markedly similar to the Bearing Sea Patrol that the Revenue Cutter Service presently performed. He stated that revenue cutters could perform the same duties in the North Atlantic much more economically than the large cruisers and that the Revenue Cutter Service should assume these duties. He cited a 1906 act of Congress as the authority. The Revenue Cutter Service conducted its first Ice Patrol in 1913 in praiseworthy fashion.

Revenue Cutter Service supporters within the federal government, the press, and the general public fought the move to eliminate the Revenue Cutter Service. The press reviewed the Service’s record and reported cutter rescue activities in detail. Editorial comment was heavily in favor of the retention of the Revenue Cutter Service. Captain Commandant Bertholf was also very active in promoting Revenue Cutter Service accomplishments and capabilities.

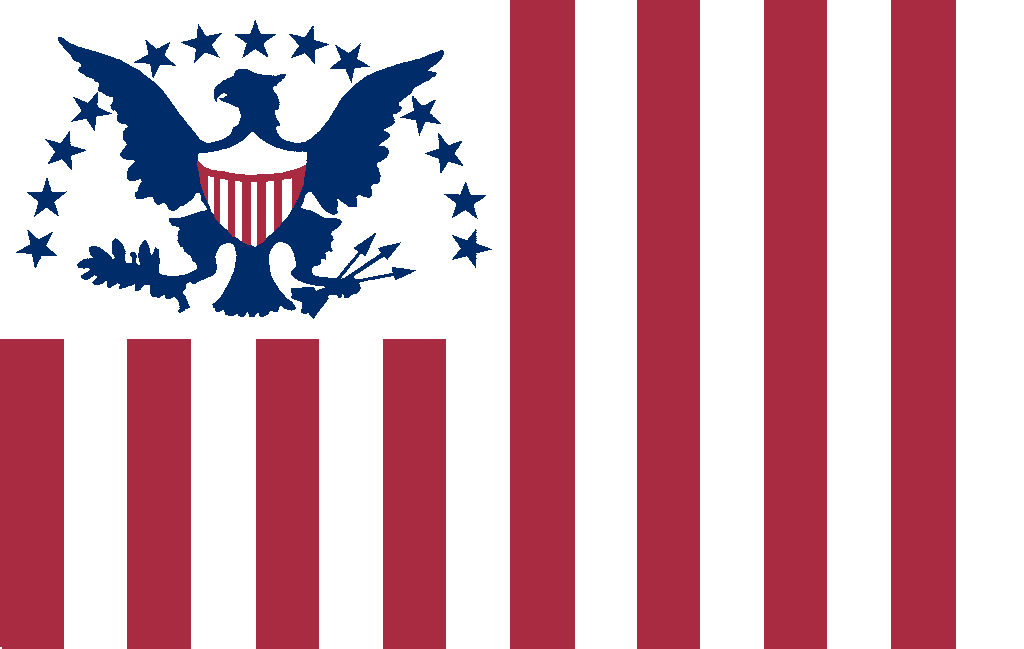

The Revenue Marine was established in 1790 to enforce the tariff and all other maritime laws and until 1798 was the only armed military service of the United States. During the War of 1812 the Revenue Marine Service and its cutters were placed under the command of the United States Navy. In 1832, Secretary of the Treasury Louis McLane ordered in writing that revenue cutters were to conduct winter cruises to assist mariners in need. Congress made the practice an official part of regulations in 1837. The Revenue Marine Service again served under the Navy in the Mexican-American War of 1848. In 1861 the Revenue Cutter Harriet Lane fired the first shots of the American Civil War. The Revenue Marine was renamed the Revenue Cutter Service in 1862. The Revenue Cutter Service participated in the Spanish American War in 1898.

In 1848 Congress appropriated funds for the establishment of unmanned life saving stations along the New Jersey and Massachusetts coasts. Between 1848 and 1854 other stations were built and loosely managed. They were run with volunteer crews, much like a volunteer fire department. The Revenue Marine Service was charged with administering them and thus the initial relationship came into being. The Great Carolina Hurricane of 1854 highlighted the poor condition of the equipment, the poor training of the crews and the need for more stations. Additional funds were appropriated by Congress including funds to employ a full-time keeper at each station and two superintendents. In 1871 the system of stations was officially recognized as a service and Sumner Increase Kimball was appointed Chief of the Treasury Departments Revenue Marine Division. Kimble convinced Congress to provide additional funds to operate the stations and to employ crews full-time. New stations were built and regulations and standards were established. In 1878 the network of life saving stations were formally organized as a separate agency of the Treasury Department and was named the Life-Saving Service.

Treasury Secretary MacVeagh and the Taft administration left office in March of 1913. The new Secretary, William G McAdoo, was thoroughly briefed and the Wilson administration strongly backed the Treasury Department’s proposal to merge the Revenue Cutter Service and the Life-Saving Service. It was sent to Congress in 1913 and introduced in the Senate to be considered by the Committee on Commerce. It was adopted without exception on 12 March 1914. However, in the press of activities generated by the incoming administration the Senate bill was not scheduled on the House Calendar. President Wilson was apprised of this and addressed a note to the House Democratic leader, as follows:

White House

Washington

December 19, 1914Hon. Oscar W. Underwood

House of RepresentativesDear Mr. Underwood: I hope that you will not think I am unduly burdening you if I write to express my great interest in the bill which has been passed by the Senate and is pending in the House which provides for the consolidation of the Revenue-Cutter and Life-Saving Services. It is of the highest consequence for the efficiency of both services that this bill should pass, and I hope that some chink may be found for it even in the rush hours of the House Calendar.

With warmest regards,

Faithfully yours,

Woodrow Wilson s/s

The bill was worked into the House Calendar. Representative William C. Adamson of Georgia, an advocate for combining the two services, steered it through the House. He advocated passage of the bill principally on the grounds that the bill would (1) reorganize the two services on a logical basis and result in increased efficiency, (2) improve the status of the life-savers facilitating the recruitment of desirable men, and (3) create a naval reserve; without additional cost to the Government; immediately ready upon notice to operate under the Navy Department whenever the President directs. Recognizing that World War I was in the initial stages, Mr. Adamson further suggested to Congress that:

“While the question of national defense now more than ever before is brought into prominence, it is well to consider the advantages of a Coast Guard from a strictly military standpoint ….. The very nature of the emergent duties in peacetime will make its members quick to action, resourceful, and disciplined, all of which, it must be admitted, are absolutely essential to success in modern sea fighting …. Simply by a stroke of a pen, the President can transfer this highly efficient corps of men, armed, trained, and disciplined, into the regular Naval Establishment at any time …. This asset of military preparedness must therefore not be overlooked when appraising the value of a Coast Guard to the Government.”

Mr. Adamson was highly effective. After a debate that centered more upon cutter officer and surfman pay and retirement benefits than conceptual issues the Act to Create the Coast Guard was approved on 20 January 1915 by a vote of 212 for and 79 against. The yes votes were spread evenly between both major parties. President Wilson signed it into law eight days later.

The name Coast Guard had it’s origin in European usage. The Spanish had attempted to prevent illegal trade with its New World colonies during the1600 and 1700 hundreds by utilizing intercept vessels known as guarda costa. In 1822 the British Government had given the name “Coastguard” to an organization of coast watchers that reported smuggling activity and vessels in distress, and acted as a naval reserve. The term Coast Guard had been applied informally, from time to time, to the Revenue Cutter Service during the late 1800s. Captain-Commandant Bertholf deemed this to be the logical name for the new service and it found ready acceptance with the public.

Captain-Commandant Bertholf, appointed for a second term, faced the delicate challenge of combining the civilian Life-Saving Service and the military Revenue Cutter Service –- organizations with vastly different cultures – into a single military service. Bertholf was absolutely convinced that the military character of the Revenue Cutter Service had to prevail but large numbers of lifesavers did not wish to change status. As a result the two services were joined at the top but operated as separate entities until events accelerated the development of a fully integrated modern security force.

Note:

Congressman Adamson’s contributions both outside and within the Congress were of significant magnitude. He was referred to on numerous occasions as the “Father of the Coast Guard.” Mr. Adamson was presented an ornate silver loving cup with the following inscription:

“Presented to HON WILLIAM CHARLES ADAMSON, member of Congress from Georgia, by the OFFICERS of the UNITED STATES REVENUE CUTTER SERVICE as a slight token of friendship and of their admiration of his able and disinterested efforts in their behalf.”