“In Keeping With The Highest Traditions”

Walter was a Coast Guard Aviator, a life saver, a risk taker and yet so very much more, He was a unique blend of talent, individualism and bonding that is difficult to understand unless you have “been there.”

In an era when Coast Guard Aviation was an adjunct – the aviators took justifiable pride in what they were able to accomplish and were humbled by what they couldn’t. They projected an aura of camaraderie and dedication — understood by many and resented by some.

Soon after joining the Coast Guard, Walter took advantage of the opportunity to learn to fly. From there he became a member of a small cadre of intrepid fully committed individuals engaged in the development and the promotion of the helicopter. Flying underpowered, weight-limited, short range, fragile aircraft – the efforts of Walter and the others lead to the saving of tens of thousands of those in peril. Walter would go on to accomplish many things with skill and dedication during his 25 years of service to Country, Humanity and the United States Coast Guard —– This is his story.

Walter C. Bolton

A Chronology of Events and Achievements

Walter was born June 19, 1919, the son of. Milo and Margaret Bolton of Milton, Massachusetts. Walter graduated in the 1937 Class of the Boston Trade School, where he took classes in aircraft and engines. .He enlisted in the Coast Guard in 1939 and was stationed on the Coast Guard Cutter Chelan, based at Boston, A year later he transferred to the Coast Guard Air Station at Salem, Massachusetts.

Walter was born June 19, 1919, the son of. Milo and Margaret Bolton of Milton, Massachusetts. Walter graduated in the 1937 Class of the Boston Trade School, where he took classes in aircraft and engines. .He enlisted in the Coast Guard in 1939 and was stationed on the Coast Guard Cutter Chelan, based at Boston, A year later he transferred to the Coast Guard Air Station at Salem, Massachusetts.

The Coast guard was expanding its aviation capabilities and in need of pilots, had opened up flight training to enlisted personnel. Walter applied for training, was accepted and transferred to CGAS Elizabeth City North Carolina for initial training. From there he progressed to the Naval Air Station Pensacola where he received his wings as a Coast Guard Aviation Pilot in July of 1942.

Walter’s initial flight assignments were aboard the CG cutters Northland and Storis in Greenland waters where he flew the J2F-5 and J2F-6. amphibious aircraft carried aboard. the Coast Guard Cutters Northland and The Coast Guard Cutter Storis.

From there it was to the Coast Guard Air Station Brooklyn, located on Floyd Bennett Field, New York where he flew Anti-Submarine Patrols. It was here that Walter, called “Red” by many, due to the color of his hair, met the helicopter.

The Chief of Naval Operations approved and dedicated the Coast Guard Air Station Brooklyn as a Helicopter and Training Base on 19 November 1943. The Coast Guard Anti-Submarine duties had been turned over to the Navy but some of the previous Coast Guard personnel remained at the Brooklyn Air Station. CDR Erickson and LTJG Graham, previously trained at Sikorsky, flew the first helicopter in. Erickson. is quoted as saying, ” We were not received or greeted with open arms. The Air Station personnel looked at the helicopter, then at us in bemusement, as if to say, “better you guys in that thing than us”

Both Erickson and Graham began soliciting those interested in learning to fly the helicopter. Erickson was Coast Guard helicopter pilot number one. Graham was Coast Guard helicopter two. Walter Bolton volunteered and became Coast Guard helicopter pilot number three on December 30,1943. Walter remained at Brooklyn training base, serving in multiple capacities; rescue missions. research and development, helicopter promotion activities and flight instructor.

Early Rescue

On 3 January 1944, devastating explosions ripped the destroyer USS Turner, DD-648, apart while anchored off Ambrose Light near Lower New York Bay. Rescuers brought survivors to the nearby hospital at Sandy Hook, and the wounded urgently needed blood plasma. Delivery by ground vehicle was not available and all airports in the greater New York area were closed due to a severe winter storm. With special permission Erickson, with Bolton as co-pilot, departed in the blinding snow storm for Battery Park, in lower Manhattan, where the needed plasma could be picked up. Two cases of plasma were lashed to the floats. Bolton stayed at the Battery due to the added weight of the plasma. The helicopters were that weight critical. With trees in front of the helicopter, Erickson backed out the helicopter and the plasma was delivered. It is of note that the helicopter was not equipped for instrument flight requiring sight of the water at all time while flying at mast height amongst ships in the harbor areas. This was the first helicopter rescue mission

Four months later on April 3, 1944. Bolton picked up a young boy who was trapped by high winds and rough water on a sand bar in Jamaica Bay The boy, Harry E. Lundmark, is believed to be the first person rescued by helicopter.

Malaria

During World War II, in the South Pacific region, Malaria, transmitted by the Mosquito, was a problem. It also was and had been a problem in specific areas of the United States; especially in the Southeastern region, where a significant amount of military training was conducted. Captain William Kossler, Chief of Aviation Engineering Division, felt strongly that the helicopter would be very effective in spraying larvicides before the mosquito larvae became mosquitoes Mosquito larvae is found on the surface of small lakes, ponds and stagnant water. He believed the helicopter’s maneuverability and flight characteristics would be exceptionally good at low level targeted spraying.

Kossler created a joint Navy/Coast Guard Department of Agriculture malaria control project. Members included Lt Joseph Yuill, a Navy entomologist from the Navy’s Bureau of Medicine who had previous experience working with aerial spray projects joined the project in October of 1944. A mixture of DDT and oil was carried on board in a tank with pump and spray booms

extended out on each side of the helicopter. Initial spraying was conducted by Dave Gershowitz and crew in the New England area and the marsh land of New Jersey. The initial evaluation was satisfactorily completed. It was then off to the tropical regions of Florida where Walter Bolton and crew joined the project. Both crews were based out of CG Air Station St. Petersburg. The work continued. Extensive work continued throughout the winter in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The results proved to be very effective. By 1951 Malaria was no longer a significant public health threat. Aerial spraying did not become a mission of the Coast Guard. However, the techniques and equipment developed by these men where the foundation for a worldwide industry.

Promoting the Helicopter

Erickson actively sought out means to demonstrate and promote the helicopter’s capabilities before the public and prominent officials. Bolton was a participant and pilot in many of these endeavors. Two such events are as follows:

In November of 1944, Walter with Dave Gershowitz as co-pilot flew a HNS-1 helicopter from New York to Chicago to participate in the Sixth War Loan Exhibition. A series of demonstrations featuring the rescue hoist, were conducted. Walter was interviewed on a CBS Radio Network program and was asked how they got from New York to Chicago. Walter, with no attempt at humor or sarcasm, explained that they left New York, flew low to the ground, had to make about 20 stops and just followed the highway signs.

In May of 1945 the greater Boston Massachusetts area celebrated National Aviation Week. One of the features was a Coast Guard helicopter duplicating Paul Reveres Route travelled in 1776.The flight, with LT. Walter Bolton at the controls. The Boston Herald newspaper estimated that more than 50,000 people watched the flight during which the maneuverability of the helicopter was demonstrated. One of the most interested spectators was Governor Tobin and party who were aboard a boat in the Charles River. Water rescue capabilities of the helicopter were specially conducted.

Upgrades and Developments of Rescue Capabilities

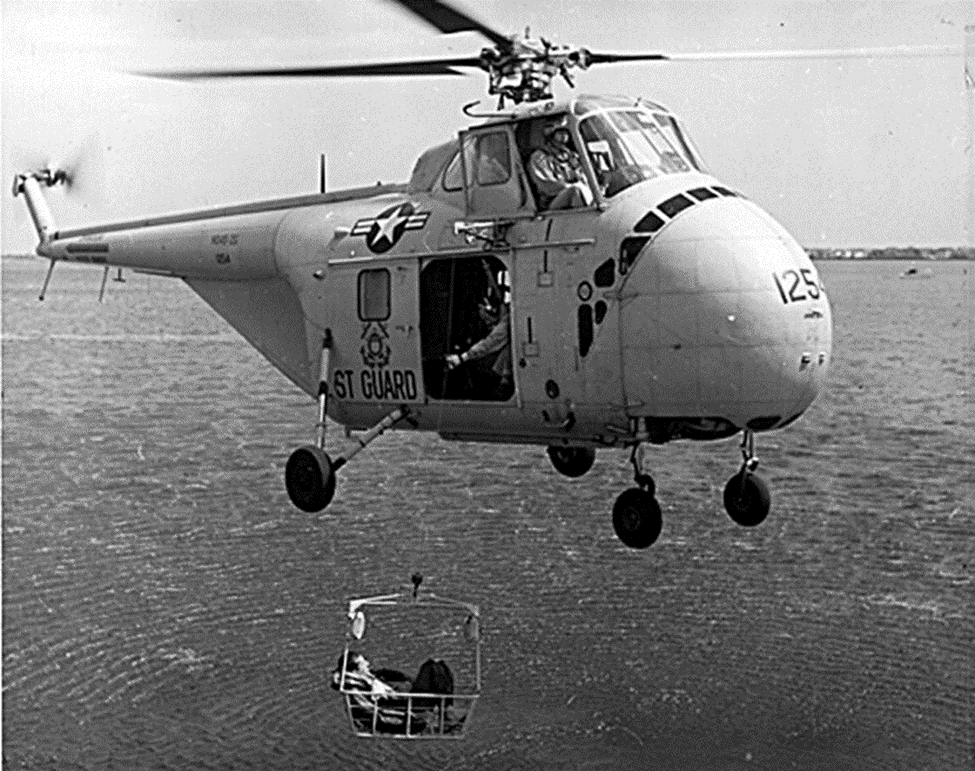

The upgrade and development of helicopter capabilities was a continuous effort. The development of the Hydraulic Hoist, that enabled the helicopter to rescue a person directly from the water. while in hover was a tremendous breakthrough. Originally’ a horse collar rescue ring was used but that gave way to the much superior and safer Rescue Basket that actually could scoop a person out of the water if needed An additional project, one of several, was to provide stretcher capability to transport injured persons.to a medical care facility. Walter was part of this project. The injured person was carried in a detachable “stokes litter “ a wire and steel basket designed to accommodate the human body. Use was limited until the Korean War Captain Dave Oliver in his Oral History states that Frank Ericson, during the Korean War was assigned temporary duty in Japan to consult and assist in developing the liter configuration on the Bell helicopters used to transport the wounded to the Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals.(MASH) This saved many lives. MASH activities were depicted on a TV show by that name.

Operation Frostbite:

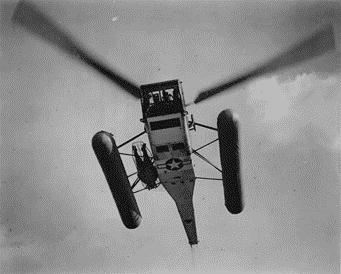

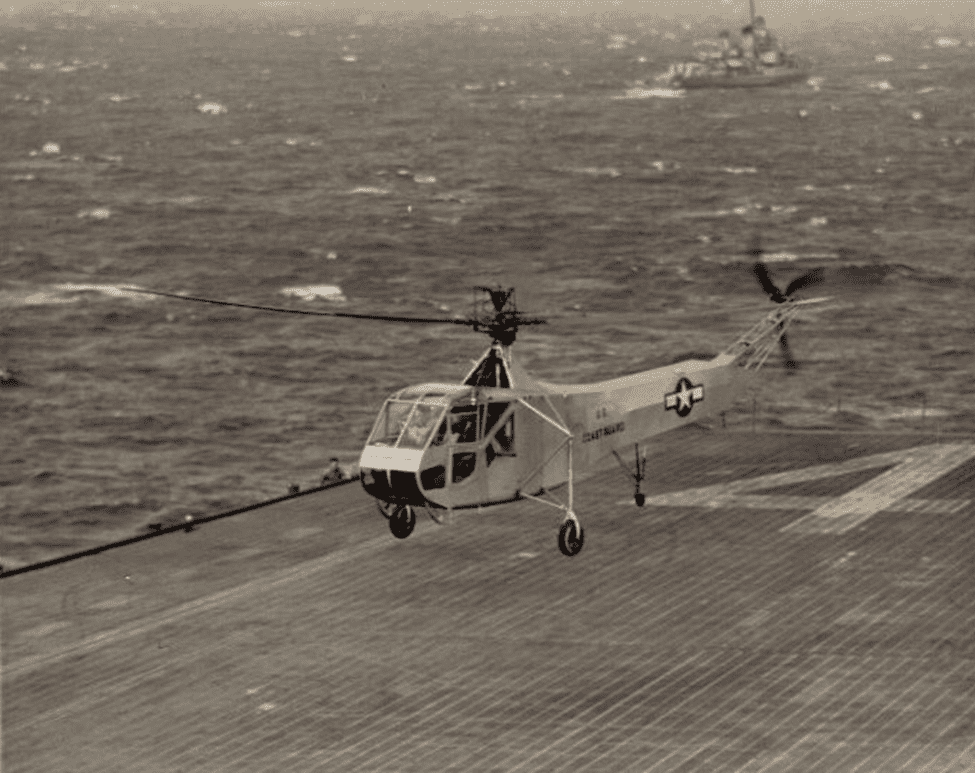

World War II was over and trouble with the Soviets was starting to brew. This prompted the Navy to evaluate the capability of a Carrier Task Force to engage an enemy, barely accessible from the sea, in near Artic conditions. Real experience was needed. In 1946, preparations for Operation Frostbite began in Norfolk, Virginia. The aircraft carrier, USS Midway, was stocked with arctic gear, including tons of aircraft engine covers and heaters, winter clothing, and flight deck snow sweepers. On February 23rd, Air Group 74, comprising F4U Corsair fighters and SB2C Helldiver dive bombers, was placed aboard. The Coast Guard also brought aboard its pioneering canvas and metal HNS-1 helicopter.

On March 1, 1946, The USS Midway departed Hampton Roads, VA and set course for the icy waters of Davis Straits between Labrador and Greenland. They encountered high winds, heavy seas, snow, and green water over the bow. Icebergs were found as well. In addition to fixed wing aircraft flights operations and refueling of escort vessels in adverse weather conditions the Coast helicopter was evaluated for rescue operations, inter surface vessel transportation and radar calibration. The daily flights of the helicopter, flown by LT. Walter Bolton USCG, claimed a good deal of attention.

Lessons learned were invaluable in the Korean War that came four years later. In addition to cold water survival gear helicopters were employed in plane guard on board aircraft carriers, standing by to recover pilots forced to ditch during flight operations.

The Belgian Sabena Airline crash – New Foundland, Canada

A Sabena Airline DC 4 departed Brussels Belgium For New York, USA, on September 17, 1946. Scheduled trans-Atlantic flight as we know it now was in its infancy in 1946, A Fuel stop at Shannon Ireland and Gander Newfoundland would be required Upon arrival at Gander the weather was extremely poor and the aircraft was diverted to a second airport. Radio contact with the DC4 was lost and Gander declared an alert and search and rescue agencies were notified. One of the first was the Coast Guard Air Detachment at Argentia. A PBY-5A was launched to search the areas of highest probability as soon as possible in marginal weather but it was not until. The wreckage and survivors were found the next morning by a TWA DC-4 Inbound to Gander. The Coast Guard PBY5A was immediately on scene and survival gear, medical supplies and sleeping bags were parachuted to the survivors.

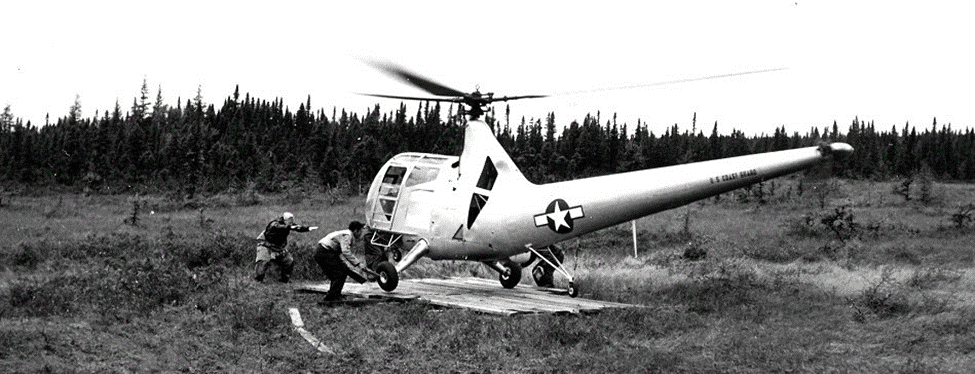

In order to reach the crash site, the rescue party was flown in to a lake up stream of the survivor location and the rescue party portaged to the crash site. The number of survivors and the trip downstream convinced the rescue party that there had to be another way. There was. The answer would be the helicopter. The helicopter had been in the development stage for four years. However, the only two rescue helicopters available in the United States, a HNS-1 and a HOS-1 were at two Air Stations on the East Coast.

Not having the range or speed to fly directly to Newfoundland they were disassembled, flown to Gander in an Army Air Force Transport Command C-54s and then reassembled. In the middle of the night a AAF C54 lifted off from Floyd Bennet Field helicopter pilots

Walter Bolton and Gus Kleisch plus maintenance crew and a HOS-1 helicopter. A Second AAF C54 lifted off from the Elizabeth City Air Station with pilots Frank Erickson and Stew Graham plus maintenance crew and a HNS-1 helicopter. Upon landing at Gander, Amazingly the Coast Guard maintenance people had the helicopters reassembled and ready to fly.

Platforms of lumber were constructed so the helicopters could land in the Muskeg. Below is the hOS-1 flown by Walter Bolton.

Instead of flying each survivor all the way to Gander they flew them to the nearby lake where they were rafted out to a PBY-5A, flown to Gander and then transported to the hospital. A total of 17 souls were rescued by the helicopters. The dead were buried on the hilltop at the crash site.

The Belgium Government Awarded the Knight of the Order of Leopold to the pilots. The Coast Guard awarded the Air Medal to the pilots and letters of commendation to the support personnel.

The New York Times summarized this rescue as “One of the strangest and most successful rescues ever undertaken,”

Newfoundland Deja Vu

Six months after the rescue of Survivors of the Belgian Sabena Airline crash Walter found himself back in New Foundland. On 24 March 1947, an Army Air Force C-54 crash landed on a high plateau, 25 miles south west of Stephenville, Nova Scotia, Canada, inbound to Harmon Field. .A search the next day located the downed aircraft. Personnel were observed walking around the aircraft. Survival kits were dropped. The terrain at the foot of the plateau was marsh and wilderness with no roads into the area. So once again the call went out to the Coast Guard

At 5.09 pm the following day an Army Air Force C-54 departed Floyd Bennet Field with a disassembled Helicopter, Coast Guard LT. Bolton and maintenance crew were on board headed to Stephenville. In the reassembled helicopter, Walter flew the injured first man out the next morning and continued one at a time until all nine were rescued. There were no fatalities.

San Francisco

The Spring of ‘47 found Walter at Coast Guard Air Station San Francisco.

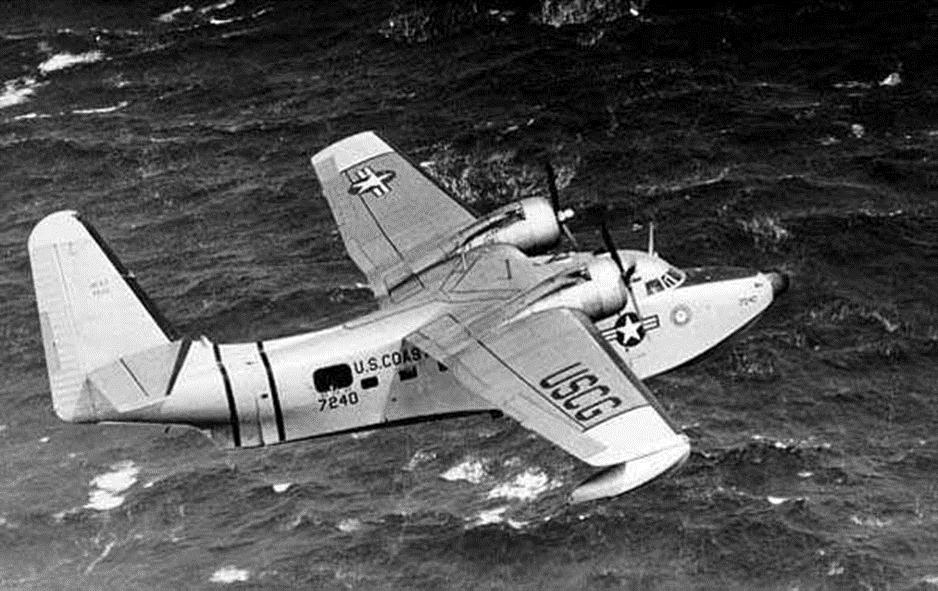

On July 11, 1949 a call came in with reference to a woman on board the S.S. Dona Aurora, 400 miles west of San Francisco, who was in in critical condition suffering from Sprue, a tropical disease which cases loss of blood. The medicine requested was obtained and a PBM launched. Ira Mc Mullan was the pilot and Walter Bolton was the co-pilot. The plan was to drop the medicine by parachute. Arriving on scene the Ships Doctor requested the patient be evacuated to a hospital ashore. Walter related that on the landing attempt the aircraft bounced twice and when power was applied to regain flight an engine quit. The aircraft struck the face of a wave, broke apart and sank within eight minutes. Walter wrote that the cockpit was flooded could not get his window to work. The cockpit had broken off and was sinking but he did not know it at the time. He swam around and went out of the pilot’s window, inflated his life vest and when he reached the surface, he was next to one of the crew with blood running all over his face. Miraculously no one was killed. One broken arm and everyone was bruised and cut up. The S.S. Donna Aurora launch a boat and everyone was picked up. Walter noted that for some reason the Pharmacist Mate in the PBM crew had put some vials of the medicine in his pocket. This this was administered to the woman and her life was saved.

In Walters Flight Log Book during his time at San Francisco, there were limited entries for flight in a HOS-1 helicopter but I could not find a reference verifying any helicopters at San Francisco during the period Walter was there.

International Ice Patrol

1950 found Walter at the Elizabeth City but again headed for Newfoundland. Walter, along with LCDR Crosby, Lt. Rusty Rast, Lt. Bob Lawlis, and Lt. R. Cunningham, would spend the next six months at CGAD Argentia Newfoundland on International Ice Patrol duties.

At 11:40 pm April 14, 1912, four days after departing Southampton, England, the RMS Titanic collided with an iceberg 400 miles south of Newfoundland, with the loss of over 1500 people. This disaster was the impetus for the establishment of the International Ice Patrol. The representative of the world’s various maritime powers, provided for an international derelict-destruction, ice observation, and ice patrol service, consisting of vessels which would patrol the ice regions during the period of danger from icebergs and attempt to keep the trans-Atlantic lanes clear of derelicts during the remainder of the year. The United States Government was invited to undertake the management of the service with the expense defrayed by thirteen nations interested in trans-Atlantic navigation. On February 7, 1914, the President of the United States directed the Revenue Cutter Service to begin the International Ice Patrol as early as possible. The Revenue Cutter Service became part of the U.S. Coast Guard in 1915.

From its inception until the beginning of World War II, the Ice patrol was conducted by two Coast Guard Cutters alternating surveillance patrols of the southern ice limits. In 1931 and thereafter a third cutter was assigned to perform oceanographic observations in the vicinity of the Grand Banks. With the resumption of the Patrol after World War II aerial surveillance became the primary ice reconnaissance method with surface patrols phased out except during unusually heavy ice years or extended periods of reduced visibility. Use of the oceanographic vessel continued until 1982, when the Coast Guard’s remaining oceanographic vessel was converted to other uses. The aircraft has distinct advantages for ice reconnaissance providing much greater coverage in a relatively short period of time.

During the period 1947-1982 visual aerial reconnaissance was conducted. Compared to today’s standards the procedures used were rudimentary and unsophisticated. The primary navigation available was LORAN-A. The radar in use could not distinguish between a ship and an iceberg so during periods of reduced visibility, when a radar contact was made, the aircraft would approach the target at an altitude of 300 feet, determined by a radio altimeter, for visual identification. The flight path flown resulted in the target passing close in on the starboard side of the aircraft. When an iceberg was identified its position was noted and logged into the flight report which was turned in upon return to base. The Ice Patrol maintained a hand plot of iceberg positions and predicted motion.

The aircraft in use during Walters deployment was a PB1G. Th PB1G was the WWII B-17 modified for search and rescue operations. The PB-1G search track was 1000 miles and the normal mission was 12 hours.

Coast Guard Air Detachment Barbers Point, Hawaii

Walter arrived at the Coast Guard Air Detachment Barbers Point Hawaii in January of 1951’ The mission was Search and Rescue and logistic support.

The first permanent Coast Guard aviation unit in the Hawaiian archipelago was established in 1945 at the Naval Air Station Kaneohe. NAS Kaneohe, was a major advanced training base for Pacific operations during World War II. The Coast Guard Air detachment, consisting of a PBY-5A and one JRF, was established to provide air-sea rescue services. The JRF was retained but the PBY was replaced by two P4Y-2s Privateers. The P4Y-2s were also used for Pacific supply runs. The Coast Guard had been charged with the continued operation of LORAN after World War II. The LORAN stations were consolidated and modified to support post war requirements. The Loran Stations west of Hawaii were supported by surface vessels and aircraft based at Guam, Sangley Point, P.I. and Barbers Point

The runs went from Kaneohe to the MATS terminal at Hickam Field, then Johnson Island, Majuro, Kwajalein, Guam, Sangley Point to Japan and then back through Wake, and Midway. The trip took between 20 and 28 days. The detachment transported everything that ATC or MATS would not carry and went to places they did not go.

In 1949 the Navy decommissioned the Kaneohe Air Station and the Coast Guard Air Detachment moved to NAS Barbers Point on the west coast of Oahu and was established as a Coast Guard Air Facility. During 1949. In 1950 two R5Ds (civilian designation DC-4) replaced the P4Y-2Gs. The mission support of Coast Guard facilities throughout the Pacific continued to grow and those that supplied them became known as “Cosmic Overseas Airways.” Although there have been several reasons advanced with reference to the origin of the name, none are verifiable. The use of the call sign “Cosmic Air” was known throughout the Western Pacific.

The Korean War began in June, 1950. As the war progressed, most all of the war material bound for Korea went by ship but nearly half of the personnel went by air. In late 1951 the Navy requested that the Coast Guard provide additional aircraft search and rescue capability. Coast Guard Air Detachment Barbers Point with subordinate units at Midway Island and Wake Island, became the major air search and rescue unit in the central Pacific. Strength and capability was increased at CGAD Barbers Point, CGAD Guam and CGAD Sangley Point in the Philippine Islands. They were on call 24 hours a day. The Midway Air Detachment had a P4Y-2G and a PBY. Aircraft and aviation personnel were permanently assigned as part of the SAR Group. Three additional Ocean Stations had been added and an Ocean Station Vessel rotated through Midway for Search and Rescue duty for consecutive three-week periods. The aircraft and Cutters worked together as a unit. Wake’s Group Commander had an 83-footer permanently assigned. P4Y-2G aircraft and crews were supplied on a monthly basis from Barbers Point.

The CGAD Barbers Point Search and Rescue aircraft were primarily engaged in the intercept and escort of military and commercial aircraft that had experienced engine failures. The reason for intercept was both psychological and the exact position of aircraft in distress would be known if ditching took place eliminating the “search” in the Search and Rescue equation. In addition, if a ditching occurred, the escorting aircraft could drop additional rafts and survival equipment, provide communication and DF steers to rescue units.

Walters Flight Log Book shows he flew both the logistics and Search and Rescue missions.

Coast Guard Air Station Salem

Walter arrived at the Coast Guard Air Station Salem, in January 1954.

Air Station Salem was located at Winter Island, an extension of Salem Neck which juts out into Salem Harbor. The aviation facilities consisted of a single hangar, with repair capabilities, a paved 250 ft parking apron, and two seaplane ramps leading down into the waters of Salem Harbor. Barracks, administrative and dining facilities and motor pool buildings were also part of the complex. Salem was a seaplane operation’

Recognizing that weather conditions could render the seadrome inoperable from time to time and that night operations in Salem Harbor had become hazardous, a sub-unit, Coast Guard Air Detachment Quonset Point, was established at the Naval Air Station Quonset Point, Rhode Island. With a complement of one Albatross amphibian, four pilots, and eight crewmen, Quonset was responsible for supplementing Salem planes during rescue operations and for fixed-wing flying when Salem could not provide it.

In 1953 the first of 24 HO4S-3G helicopters were obtained by the Coast Guard. Some of these were based at CGAS Salem. The HO4S-3G helicopters extended the Coast Guard’s rescue capabilities far beyond the HNS-1 helicopter that Walter first qualified in, just a decade prior. Although underpowered by today’s standards it was the first operational helicopter capable of carrying heavy loads and multiple survivors in a cabin. The Coast Guard 3G model was the first helicopter fully capable of flying in flight instrument condition weather. These helicopters would perform numerous rescues during the next decade, some best described as miraculous, within parameters never before achieved.

Walter’s Log Book shows that he flew both the HO4S-3G and the UF Albatross while at Salem.

Coast Guard Air Station San Diego

In the Spring of 1957 Walter was transferred to Coast Guard Air Station (CGAS) San Diego. During this tour Walter flew the UF2G amphibian, the P5M-2G seaplane and the HO4S helicopter. Unlike CGAS Salem where Walter spent most of his time at Salem’s Quonset Point Air Detachment flying UFs, the preponderance of his flight time at CGAS San Diego was in the HO4S-3G

The HO4S- 3G helicopter extended the Coast Guard’s rescue capabilities far beyond what was imagined when Walter first climbed into pilot seat of the HNS-1 14 years prior. Although underpowered by today’s standards it was the first operational helicopter capable of carrying multiple survivors in a cabin and carry heavy loads. It had a rescue hoist capable of lifting 400 pounds and could fly at a normal forward speed of 80 knots with a range of 350 nautical miles. It proved, beyond all doubt, the capabilities and value of the helicopter for Coast Guard operations.

With Military Air Bases in the area, a multitude of Marinas in San Diego Bay and traffic up and down the coast, Search and Rescue activities were a major responsibility. This was reflected in Walter’s Flight Log Book. The entries were brief, appeared routine but each denoted an incident that was highly significant in the eyes of those who had been rescued.

Coast Guard Cutter Taney

During World War II, forty percent of Coast Guard aviators were Aviation Pilots (APs). The AP’s were highly qualified Enlisted Men who earned their wings at NAS Pensacola. All but the last classes of Coast Guard Aviation Pilots were later commissioned as Officers but when the Reduction-In-Force occurred after the War, some left the service and others reverted to Enlisted Status. In 1952 all Aviation Pilots (APs) on active duty were offered permanent Officer status. All but six accepted. When I came on board these gentlemen were senior duty officers, Operation officers and Executive Officers. The Coast Guard Aviation Pilots (APs) had a very positive effect on Coast Guard aviation and contributed greatly to our heritage.

In the late 1950s a Coast Guard Directive was issued requiring all Aviators, to have served a tour of duty aboard a Coast Guard Cutter, as a prerequisite for promotion to the rank of Commander. This of course directly affected the former APS. To say that this was not looked upon favorably by the Aviators is a significant understatement. By many it was looked upon as a breach of faith.

The United States Coast Guard kept a high endurance cutter on station between Hawaii and California at a designated location known as Ocean Station November. This ship, operating within a 10-mile grid, provided assistance with weather information, radio communications, a continuous signal that trans- Pacific aircraft used as a navigational aide and was available to assist should an emergency arise aboard trans-Pacific airplanes. The CGC Taney, based out of Alameda, California operated in support of Ocean Station November.

Walter reported aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Taney in August 1959. He was the executive officer.

The last Duty Station

Walter left the Taney in June of 1961 for Staff Duty Commander Coast Guard District Seventeen.

Walter retired on July 1,1964 as a Commander. He flew West on June 8 1976

A sincere thank you Walter:

For service exceptionally well done in keeping with the highest traditions

John Bear Moseley

Coast Guard Aviator # 743