Dave was born on 31 December 1918, in Brooklyn New York. He attended public school and was graduated in 1937 from Thomas Jefferson High School. Four years later he graduated from the New York State Agricultural College in Farmingdale, Long Island.

He enlisted in the Coast Guard on 2 January, 1942 and underwent recruit training on Ellis Island in New York Harbor, graduating as a Fireman Third Class. He was assigned to the Rockaway Lifeboat Station as a Water Tender Second Class. Three months later he reported for flight training at Grosse Isle, Michigan followed by advanced flight training at the Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida.

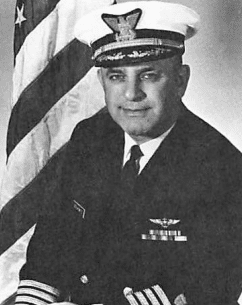

Dave completed flight training as an Aviation Pilot 1st Class (AP 1) in May of 1943 and was assigned to the Coast Guard Air Station Brooklyn, New York. While at Brooklyn he attended the Helicopter Training School and upon completion was designated Coast Guard Helicopter Pilot number 7. Dave was commissioned an Ensign on March 9, 1944 and was designated Coast Guard Aviator number 132.

Malaria

During World War II, in the South Pacific region, Malaria, transmitted by the mosquito, was a severe problem. It also was and had been a problem in specific areas of the United States; especially in the Southeastern region, where a significant amount of military training was conducted. Captain William Kossler, Chief of Aviation Engineering Division, felt strongly that the helicopter would be very effective in spraying larvicides before the mosquito larvae became mosquitoes Mosquito larvae is found on the surface of small lakes, ponds and stagnant water. He believed the helicopter’s maneuverability and flight characteristics would be exceptionally good at low level targeted spraying. Kossler created a joint Navy, Coast Guard, Department of Agriculture malaria control project. Members included Lt. Joseph Yuihl, a Doctor from the Navy’s Bureau of Medicine, who had previous experience working with aerial spray projects, who joined the project in October of 1944.

A mixture of DDT and kerosene was carried on board the helicopter in a 29-gallon tank with a pump .and a spray boom with variable orifices, that extended from the tail section. Dave Gershowitz, based upon knowledge acquired while at the New York State Agricultural College, conducted the initial helicopter spraying operations that took place in the New England area and the marsh land of New Jersey. In addition to mosquitoes, Japanese Beatles and other destructive insects were included in the eradication program.

With the initial evaluation satisfactorily completed, A second helicopter was modified for spraying operations. This helicopter, flown by Walter Bolton and crew, joined Dave Gershowitz and crew in Florida. They flew out of Coast Guard Air Station St. Petersburg. The object was to illuminate malaria in the Southeast Unites States. The work continued. Extensive work continued throughout the winter in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

By 1951 Malaria was no longer a significant public health threat.

Aerial spraying did not become a mission of the Coast Guard. However, the techniques and equipment developed by these men were the foundation for a worldwide industry.

At some point during this period, Lt. David Gershowitz became Gersh.

Pawtuxet Test Center

In early 1946 Gersh received orders to proceed to the Patuxent River Test Center. It was desired to have a Coast Guard representative to keep abreast of aircraft development. Gersh was both fixed wing and helicopter qualified. In fact, at the time of his arrival he was the only helicopter qualified pilot and Gersh became the chief of the rotary wing section. Gersh said that it was during this tour that he checked out in the Bell P-59 jet aircraft.

Operation High Jump

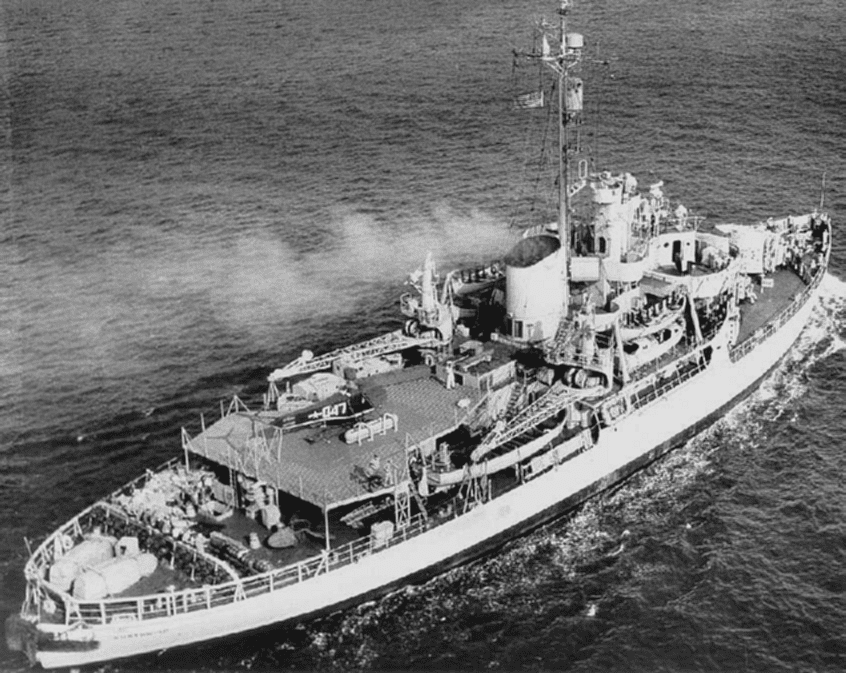

At the end of 1946 Gersh returned to the Coast Guard Air Station Brooklyn and was assigned as a helicopter pilot aboard the Coast Guard Icebreaker Northwind, participating in Operation High Jump.

High Jump, officially titled The United States Navy Antarctic Developments Program, illustrated the cold war thinking of the time. We were in the Nuclear Age and there was genuine fear that the Soviet Union would attack the United States over the North Pole. The Navy had conducted polar exercises in the summer of 1946 and felt strongly that it needed to do more. Winter was coming in the north, time was important, resulting in the follow up exercise, Operation High Jump, that took place in the South Polar Region. Politically the orders were that the Navy should do all it could to establish a basis for a land claim in Antarctic. High Jump was the most massive sea and air operation theretofore attempted in Antarctica. It involved 13 ships, including two seaplane tenders, an aircraft carrier, the Coast Guard Ice Breaker Northwind and a total of 25 airplanes.

High Jump was both strategic and exploratory. Ship-based aircraft returned with 49,000 photographs that, together with those taken by land-based aircraft, covered about 60 percent of the Antarctic coast, nearly one-fourth of which had been previously unseen. Other technological developments—such as advances in cold-weather clothing, vehicles, and fuel for overland travel—further opened up the continent’s interior for scientific exploration.

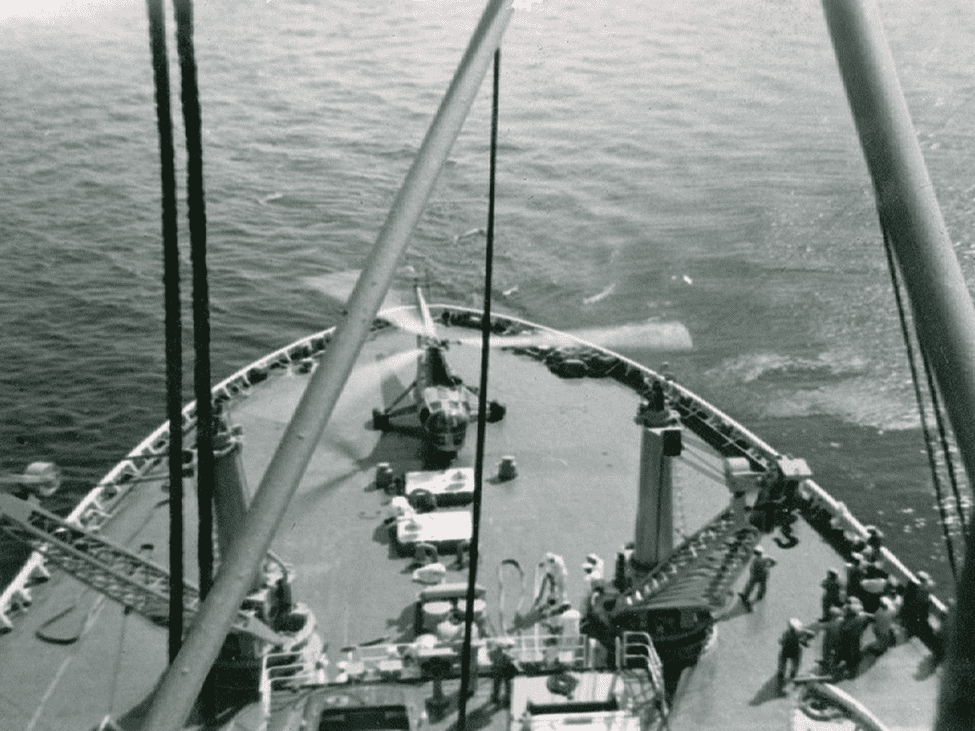

The Northwind departed Norfolk, Virginia on December 2, 1946, bound for the Antarctic via the Panama Canal with an HNS-1 and a J2F-6 on board. Upon arrival the J2F-6 performed reconnaissance, supply flights and acted as a standby rescue and medical evacuation aircraft. The helicopter served admirably in finding leads in the ice for the Northwind. The HNS-1 operated from a specially built platform and was put into immediate use. The helicopter flew at 600 feet and surveyed the packed ice that barred entry into the Ross Sea. The three pilots aboard the Northwind were Lt. Jim Cornish, Lt. Dave Gershowitz and Aviation Pilot John Olsen. Lt. Gershowitz stated that both Captain Thomas and Admiral Cruzan, who had changed his flag to the Northwind for the trip through the ice pack, went up on every suitable occasion. Gershowitz wrote that due to the low temperatures the air was very dense and greatly increased helicopter performance.

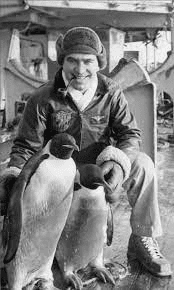

As the Northwind moved through the ice pack, the helicopter would fly slowly in front of the caravan scouting the vast area ahead looking for ice leads; – the cracks in the pack which made penetration by the convoy possible. A total of 128 flights were made in the helicopter during Operation HIGH JUMP. Gersh wrote that the emperor penguins stared at them in ill-concealed astonishment whenever they took off and landed. They named the HNS-1 the “Flying Penguin.”

The penguins were solemn, ludicrous birds that strutted like funny little human beings. Gersh had caught a few of them and tamed them to a degree. When March came and the expedition started North after completing the mission, Gersh took his penguins with him. In New Zealand, Gersh gave two to the Zoo. The Keepers immediately named one of the penguins Gersh and with newspaper coverage Gersh became somewhat of a celebrity. Two were brought back to the United States and immediately became the center of attraction at the Coast Guard Air Station Brooklyn. These Penguins found a home at the Bronx Zoo.

At the conclusion of High Jump. Captain Charles W. Thomas, the Commanding Officer of the USCG Cutter Northland wrote a letter to the Commandant of the US Coast Guard explaining why the helicopter was essential for Polar Operations. It fell on deaf ears.

After High Jump, Gersh returned to the Brooklyn Air Station. He served as a helicopter instructor and operations duty pilot.

Ice Breaker Operations – The Great Lakes:

In early 1948 CDR Frank Erickson was ordered to proceed to Buffalo, New York in a HO3S-1G helicopter and report on board the Coast Guard icebreaker Mackinaw, which was about to start the icebreaking season. With the demand for steel the greatest since World War II it was essential that the Great Lakes be opened as early as possible to transport iron ore from the Mesabe range in eastern Minnesota to the steel producing centers. CDR. Edwin J. Roland future Commandant of the Coast Guard, was assigned as Commander of a task force which consisted of the Mackinaw and several buoy tenders with icebreaking capability. CDR Harold J. Doebbler was in command of the Mackinaw. An ice survey and photographic flight of Lake Erie was conducted on 16 March and on 18 March the Mackinaw led a convoy of ore carriers out of the harbor and headed for Cleveland. It was the earliest opening of Buffalo Harbor in recorded history. CDR. Roland flew every day keeping a constant check on the ice conditions. A change of direction or force of the wind could cause windrows of ice to form or blow an ice field ashore with ships trapped in it. Advantage was taken of open leads in the ice that could only be spotted from the air. This sped up the operation considerably and as a result the Great Lakes were opened to navigation two months earlier than in the past.

The helicopter was praised in the press for its part. One aviation periodical carried the following account:

“Use of helicopters operating with Coast Guard icebreakers in the Great Lakes last winter freed icebound shipping at Buffalo 67 days ahead of schedule and increased the effectiveness of ice breaking operations by 50%. The helicopter scouted as much as 100 miles ahead of the icebreaker and determined the route of the thinnest ice ahead. It also permitted the icebreaker skipper to perform frequent inspections of icebound groups of ships to determine the most effective route for freeing them.”

Gersh was permanently transferred to the Coast Guard Air Station at Traverse City, Michigan. In addition to regular duties, Gersh was once again flying a helicopter and working with the Mackinaw breaking ice each early spring.

The Korean War

The participation of the Coast Guard during the Korean War was limited to Port Security, Oceanic Search and Rescue, LORAN navigation system operation and additional Ocean Weather Stations. This was a result of a Coast Guard Planning Committee headed by RADM James Pine after WWII that limited wartime operations to those duties normally performed by the Coast Guard.

Two additional Air Rescue detachments were established; one at the newly reopened Naval Air Station at Midway Island; one at Wake Island. The Midway Air Detachment had a P4Y-2G and a PBY. Aircraft and aviation personnel were permanently assigned as part of the SAR Group. Ocean Station Vessels would rotate through Midway Search and Rescue duty for consecutive three-week periods. The aircraft and cutters worked together as a unit. Wake’s Group Commander had an 83 -footer permanently assigned. Aircraft and crews were supplied on a monthly basis from Coast Guard Air Detachment Barbers Point, Hawaii. In July of 1952, Gersh was assigned to the Coast Guard Air Detachment Wake Island and three months later assigned to similar duties at the Coast Guard Air Detachment Barbers Point.

Distant Early Warning Line:

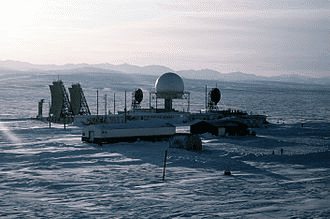

Gersh was transferred to the Coast Guard Air Station Port Angeles, Washington in March of 1954. In June of 1955 he began a temporary assignment as the Air Officer and pilot aboard the USCG Cutter Northwind engaged in the construction of the Distant Early Warning Line also known as the DEW Line. This was a system of radar stations in the northern artic region of Canada with additional stations along the North Coast of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. It was set up to detect incoming Soviet Union bombers during the Cold War and provide early warning of any sea-and-land invasion. Construction of the DEW Line began around 1955 and took 32 months to complete. It was a true engineering and construction feat. It became operational in August 1957 and most stations were decommissioned by 1994.

The Air Medal:

On August 6, 1968 Gersh was awarded the Air Medal. To appreciate the significance of this award a little background is in order. From the end of WWII to the mid 1960’s, there was a definite reluctance on the part of the Coast Guard to award individual recognition to those who distinguished themselves by heroism or meritorious achievement. I have never seen a justifiable reason for this. The recommendation for Gersh’s Air Medal listed 11 instances to support the award. In fact, as you read the instances it becomes apparent there was support for additional Air Medal presentations.

Gersh’s record lists, numerous medevacs, rescues of people off fishing boats and on one occasion when a doctor was delivered to the Ambrose Lightship to save a man’s life. This flight was made during a full gale. Gersh took part in 10 plus Mountain Rescues in the Pacific Northwest, and as a result, he was made a member of the Mountain Rescue Council

Sea Duty:

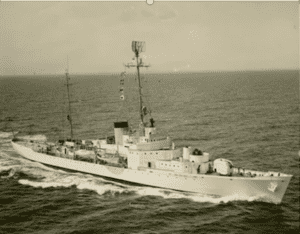

From 1959 until 1961, Gersh served as the Executive Officer aboard the USCG Cutter Spencer. The Coast Guard had initiated a program in which those Aviation Pilots that had not had a sea duty tour would be required to do so as a prerequisite to being promoted to the rank of Commander. The initial aviators excelled and the program was determined not to be necessary and was canceled after a short period.

The USCG Cutter Spencer was Commissioned in 1937 when the United States entered World War II, the Coast Guard temporarily became part of the United States Navy. During the Battle of the North Atlantic she acted as a convoy escort, hunting German U-boats. Spencer was responsible for sinking U-633 and U-173 in 1943. After the war, Spencer returned to her Coast Guard duties acting as weather station vessel, a search and rescue vessel and providing navigational assistance for the fledgling Trans-Atlantic air industry, an ocean weather station vessel and acted as a search and rescue vessel for both ships and airplane.

Shore Duty:

Upon leaving the USCGC Cutter Spencer, Gersh’s next tour of duty was the Director of the Coast Guard Auxiliary in the Thirteenth Coast Guard District. This was followed by assignment as the Captain of the Port and Chief of Intelligence in the Fourteenth Coast Guard District. In 1965 he was assigned as the Director of the Coast Guard Auxiliary and Chief of Intelligence in the Fourteen Coast Guard District. In 1967 he was the Chief of Reserve in the Ninth Coast Guard District. This was followed by a tour as Chief of Reserve in the Thirteenth Coast Guard District followed by Chief of the Port of Seattle, Washington.

Retirement:

Gersh passed away on August 12, 1995

A 1.9 million dollar, 6900 square foot, medical/dental clinic was built at Coast Guard Air Station Port Angels during 1997, to serve the active duty and retired Coast Guard Personnel in the greater Port Angeles area. The Clinic was named for Captain David Gershowitz, USCG, At the Dedication Ceremony, Commanding Officer Captain Paul Volk made opening remarks. He recognized the dignitaries and others. He went on to say” I ended my welcome with friends of Gersh because I always smiled when I heard or saw Gersh and I wanted to smile and see you smile on his great day. Of course, the proper form was and is Captain Gershowitz, but Gersh always seemed to want to be called Gersh.” And each time Paul mentioned the name they all smiled.

John Moseley

Historian CGAA

Nora Chidlow

Archivist CGHD