By Captain Art Wagner USCG (Ret)

In September 1965 at the Coast Guard Air Station New Orleans, located as a tenant at NAS Alvin Callender Field, we all watched the annual hurricane weather prognostications with a wary eye. If a hurricane were to enter the Gulf of Mexico, we would be involved in one way or another. We watched the birth of Hurricane Betsy with a somewhat detached interest as it passed to the east of Puerto Rico and veered north toward South Carolina. Then a strange thing happened, not previously seen in the annals of hurricane movement and tracking. About the time Betsy reached the latitude of Jacksonville, Florida, in the Atlantic, it did a U-Turn and headed south again! Then it did a right turn, slamming into Key Largo and then it seemed to be heading directly for New Orleans.

In September 1965 at the Coast Guard Air Station New Orleans, located as a tenant at NAS Alvin Callender Field, we all watched the annual hurricane weather prognostications with a wary eye. If a hurricane were to enter the Gulf of Mexico, we would be involved in one way or another. We watched the birth of Hurricane Betsy with a somewhat detached interest as it passed to the east of Puerto Rico and veered north toward South Carolina. Then a strange thing happened, not previously seen in the annals of hurricane movement and tracking. About the time Betsy reached the latitude of Jacksonville, Florida, in the Atlantic, it did a U-Turn and headed south again! Then it did a right turn, slamming into Key Largo and then it seemed to be heading directly for New Orleans.

The northern Gulf of Mexico is like a huge industrial area, with drilling rigs, pumping stations, capped wells scattered about and trafficked by a flotilla of workboats, freighters, tankers, and large fleets of support helicopters. On a normal day, it is a busy place, but in the advance of a hurricane, the pace rapidly picks up to a frenetic level as rigs are shut down and manned platforms are evacuated. As the weather deteriorates, and clouds and rain limit visibilities, the air traffic tends to migrate to the bayous and rivers for VFR guidance. An unwritten rule states that you fly on the right side of the bayou or river, as there is always two-way traffic in these conditions.

The Coast Guard had weathered many a storm in the Gulf, and pre-planned activities got underway. For the Air Station New Orleans that meant helping with the evacuation of some of our isolated units, responding to CCGD8 requests for flights, and finally dispersing the helicopters so as to be immediately ready for action after the passing or near miss of Betsy. When it became evident that Betsy was indeed going to hit the City, Dennis McDaniel, another pilot and a crewman deployed to Lakefront Airport on Lake Pontchartrain and were housed in a City hangar. After the Navy stuffed as many A-4s and P-2s in the Navy hangar as they could, one HH-52A was located just inside of the hangar doors on either end. The duty section was augmented and the remaining crew sent home to wait out the storm. (We had three HH-52 Helicopters and most of the time had about 8-10 pilots and 18-24 crewmembers – To cover operations we normally flew single pilot with one crewmember.)

The night of 9 September was a night to be remembered. Although I had weathered the 1938 Connecticut hurricane and at least four or five that hit Elizabeth City in my first tour, a tornado that tore through Chanute AFB and the ravages of a Northern California storm where we lost an HH-52A and crew, I was not prepared for this monster. Betsy took a bead on the City and came ashore at Port Sulfur with sustained winds of 155 mph. It continued almost directly over the Mississippi River with the winds dying to about 107 mph by the time it reached New Orleans.

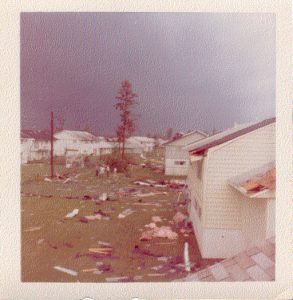

Lorna, the kids and I huddled in our two-story house after making as many preparations as we could. Shortly after dark, we lost electrical power and were treated with a Technicolor display of explosions and sparks as the various power lines, transformers, etc. shorted out. By midnight, the house was shuddering and shaking, and the water was rising in the street, gradually increasing to meet our front porch. I started to hear strange noises up in the attic, so I grabbed my flashlight, opened the linen closet and poked my head up through the small access door to the attic. Just as I did so, a large section of our roof departed, leaving a gaping hole from the front to the back of the house.

“By midnight, the house was shuddering and shaking, and the water was rising in the street, gradually increasing to meet our front porch.”

In retrospect, I made a foolish decision at that point. I had looked at all of my neighbors’ houses with my flashlight and determined that all but one suffered similar damage. Thinking that the whole house might explode with the winds blowing into the attic, I gathered up my youngest in my arms and directed that we all run next door to our neighbor’s undamaged Cape Cod designed house. Debris whistling through the air between the houses could have severely injured one of us, but we made it and rode out the storm with them.

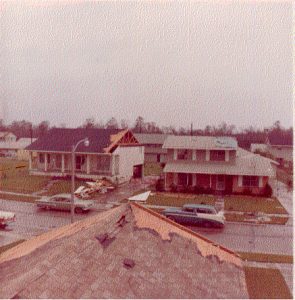

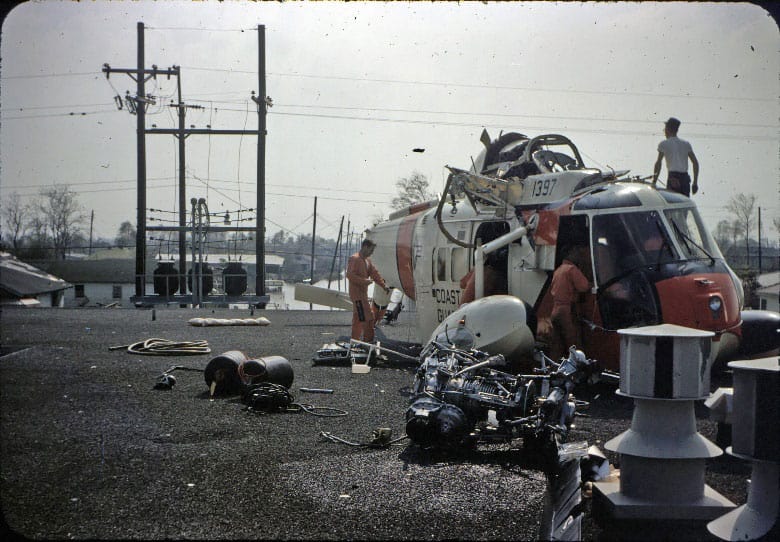

At daybreak, I formed a damage control team of my neighbors and we covered the roofs of seven houses and cleared dangerous debris away from traveled areas. About that time, ADC Tom Gass, my maintenance chief managed to drive a government vehicle through all of the debris to pick me up and take me to the Air Station. The Navy hangar was a shambles. The wind had blown out the side windows and then lifted the foamed concrete slabs that formed the roof, normally lying in metal channels and then covered with tarpaper. As they twisted, they lost lift and rained down on the A-4s and P2s, piercing wing fuel tanks – the hangar deck was awash with a mixture of 115/145 and JP-4. One of our birds was nailed, receiving direct hits on the rotor head, smashed through the fuselage in two places, and broke a rotor blade, so it was lost to any rescue efforts before we could get started.

We were left with HH-52As 1372 and 1397, but reinforcements were being rushed in from Savannah, Miami, and Houston.

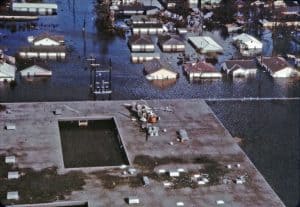

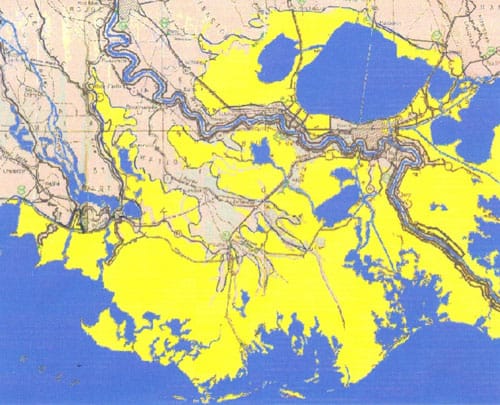

It was assumed that barges and ships tied up in the bayous, river, and the Industrial canal would be safe, but that was not the case. Barges broke loose in the height of the storm, madly ricocheting downriver, and two major ships in the Industrial Canal broke free from their moorings and holed the levee. Water cascaded into the Ninth Ward. Thousands of people had taken shelter in schools throughout the City, and those in the Ninth Ward thought they had weathered the storm as it passed, only to find the water rising rapidly to 10 ft. in the shelter and neighborhoods, forcing them all up on the roof in the rain and wind.

Our two helicopters, soon to be augmented by NAS New Orleans Navy H-34s and Houston HH-52As started a shuttle from the rooftops to dry land on the levees. The weather was not good, but flyable. Crews returning for fuel warned of panic on the rooftops, so we armed the crewmen with .38 pistols. After I had arranged for maintenance, fueling, and crew rest, I launched at around 1500 with Rod Martin III as my co-pilot and an armed AD3 from Houston. Rod had just returned from an earlier flight where they picked up over 200, so he knew the drill. We would hover over the rather fragile roof, and start loading panicky people when the torque reached about 93-95%, we would let the crewman know and he would forcibly stop the onrushing crowd. This continued for three hours until we were down to 300 lbs. of fuel or so, and took our last load of 23 passengers to the levee – 26 in an HH-52A! Our grand total was 218. That meant that Rod had been co-pilot for two flights of almost 6 hours picking up over 400 from the roof-top! (He went on to continue his outstanding airmanship flying Jolly Greens in Viet Nam.)

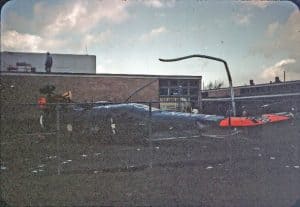

The aircraft was refueled, and a Houston pilot launched to finish the day, but he was not so fortunate, for by this time, the crowds were unruly, and they mobbed the helicopter, forcing the right wheel through the roof. The pilot naturally put in left cyclic to correct the right roll, and a main rotor blade hit a ventilator and was torn from the helicopter. Now severely out of balance, the entire MGB, rotor head and the two remaining blades departed the ship, flying over the heads of the crowd. That was the end of the day for CGNR 1397.

Our Navy friends did not fare much better, The Commanding Officer had just picked up 11 people in an H-34, and was backing off the roof, when a drop of moisture shorted out the auto throttle and rolled off power. He hit the flagpole and dropped into the water. Somehow, no one was killed in these two incidents.

New Orleans is actually below sea level in most areas, and recovery of the two helicopters necessarily had to wait until power could be restored, levees patched, and water pumped from Ninth Ward. Once that happened, we moved in with cranes and trucks and gathered the pieces, working in very depressing conditions of reeking odors, families returning to flooded homes, streets littered with furniture, mattresses, etc.

It took time to get the home front repaired and house livable, and perform the same clean-up at the Air Station, plus support the CCGD8 multitude of airborne needs. By early November, however, the Air Station took action to recognize the aircrew and submitted recommendations for the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for its pilots. However, CGHQ (OAU at the time) had a different slant on things, and the response was “We do not issue multiple DFCs” and downgraded the awards to Air Medals. And so, many months later in April 1966, our stalwart cadre solemnly stood in line and were so honored.

Note the paucity of chest confetti. There existed at the time, a negative bias towards awarding aviation personnel recognition for extraordinary achievement or heroism in flight. Aviation crew members, by nature of their primary Search and Rescue mission, have a greater opportunity for operational awards. The non-aviator viewed this simply as the aviation personnel receiving a disparate number of awards. The fact that the individual met the criteria for the award was in many cases a non-issue.

These pilots were old hands at unusual and difficult missions, standing one-in-three duty with one day standby. The duty section consisted of one pilot and two crewmembers and you knew there was a 75% chance you were going to be launched on something you had never done before.

The SAR teletype would jingle; the two crewmembers would pull the helo out on the ramp, while the pilot would man the phone or teletype and get the mission details. One crewmember would run back in to relieve the pilot, who then launched with the other man, typically in a very few minutes. I remember when a new XO reported aboard and wanted to ride with me on a night mission to get a towline on a logistics vessel loaded with 200 tons of TNT rolling on the beach in heavy surf. After threading the needle and successfully heading for home, he asked: “Are all of our missions as tough as that?” Yup, they were. You earned your pay.