Henry J. Pfeifer was born in New Brunswick New Jersey on 15 February, 1915. The family moved west to California and Hank was schooled in the Los Angeles and San Francisco school systems. He graduated from Polytechnical high School 1n 1933 and joined the Coast Guard in 1935. Hank served on the Coast Guard Cutters Shoshone, Itasca and Tampa. While on Itasca, he participated in the search for Amelia Earhart in the South Pacific Ocean. He then served in the Eighth Coast Guard District Office where was advanced to Yeoman first Class. He requested and was assigned flight training 10 December 1941. He was winged on June 14, 1942 as an Aviation Pilot First Class.

Hanks first Aviation duty station was the Coast Guard Air Station Biloxi, Mississippi. where he was assigned to the Air Detachment at Houma Louisiana. The duty was Anti-Submarine patrols in OS2U3’s and J4F-2 amphibians. Hank was commissioned as an Ensign on April 7, 1943. Biloxi was followed by a transfer to Coast Guard headquarters where he flew as co-pilot and later pilot for the Secretary of the Treasury.

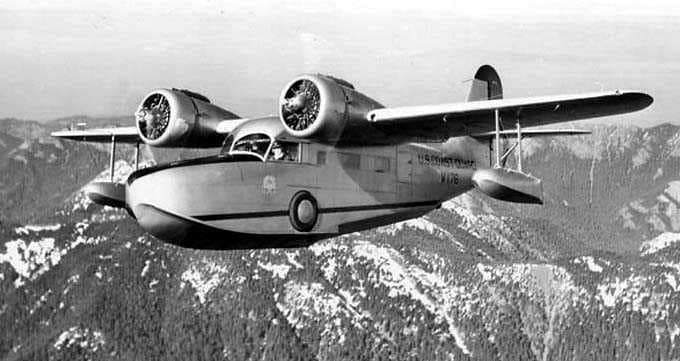

At the end of 1944 he was sent to Alaska to establish the Coast Guard Air Detachment at Annette Island, 20 miles south of Ketchikan, Alaska. The detachment consisted of one JRF number 228, LCDR J.J. McCue, Hank and 5 enlisted crewmembers. In January of 1945, Hank was transferred to the Coast Guard Air Station at Elizabeth City, NC. to open up Search and Rescue detachments at Wilmington, NC and Charleston, South Carolina. This was followed by a temporary duty assignment to the Coast Guard Academy in January of 1947, for Line Officer Training and permanent Commission. This was followed by duty aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Taney out of Alameda California for two months duty to qualify as a line Officer.

At the end of 1944 he was sent to Alaska to establish the Coast Guard Air Detachment at Annette Island, 20 miles south of Ketchikan, Alaska. The detachment consisted of one JRF number 228, LCDR J.J. McCue, Hank and 5 enlisted crewmembers. In January of 1945, Hank was transferred to the Coast Guard Air Station at Elizabeth City, NC. to open up Search and Rescue detachments at Wilmington, NC and Charleston, South Carolina. This was followed by a temporary duty assignment to the Coast Guard Academy in January of 1947, for Line Officer Training and permanent Commission. This was followed by duty aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Taney out of Alameda California for two months duty to qualify as a line Officer.

Hank transferred from the Taney to the Coast Guard Air Station San Diego in September of 1947 and was back on Aviation Duty. At San Diego there were many rescue flights to the Mexican, Baja in PBM-5’s picking up injured fishermen off the tuna boats for severe medical attention and transporting them back to San Diego. These were open sea landings. During the four years Hank spent in San Diego, one year was spent, temporary duty, on the Coast and Geodetic PB1G photo aircraft photographing coastal Alaska.

In 1951 Hank transferred to Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City NC while there he was assigned to the International Ice Patrol flying out of Argentia New Foundland. Hank qualified as Coast Guard helicopter pilot number 135 on 14 October 1952 While CGAS Elizabeth City, he flew a helicopter as a participant in the commemoration ceremony during the 50th Anniversary of flight at Kitty Hawk. North Carolina. During this period Hank was assigned a second tour on the Coast Guard PB-1G Coast and Geodetic Aircraft

From CGAS Elizabeth City, it was CGAS San Francisco. Here Hank flew logistic support in the R5D and the HO4s-3G helicopter.

The Yuba City Flood

At 12:04 a.m. on December 24, 1955, a levee on California’s Feather River collapsed resulting in a wall of water that flowed into Yuba City and surrounding farmlands. Soon after, a Coast Guard helicopter arrived on-scene to rescue survivors.

Based at Coast Guard Air Station-San Francisco, the helicopter was a newly-developed HO4S-3G. Considered by many to be the service’s first effective rotary-wing rescue platform, this helicopter far exceeded the capabilities of early Coast Guard helicopters used since World War II. It was capable of carrying a crew as well as large groups of passengers in an enclosed cabin. Standard equipment included a rescue hoist capable of lifting 400 pounds and rescue basket. In addition, the Coast Guard HO4s-3G was the first helicopter equipped for instrument flight capability and night-time operations. This was a very significant leap forward and an essential feature for rescue operations.

R George F. Thometz and LT Henry J. Pfeiffer with Chief Aviation Machinist Mate Joseph Accamo and Aviation Machinist Mate Second Class Victor Roulund alternated as crews over the next 12 hours. to avoid fatigue, The helicopter, never shut down, and was “hot-fueled” with the engine running.

Pfeiffer, the more experienced pilot and qualified for night flight, began the search operation in darkness. Flying low over the housetops, he flew between trees, high tension lines and telephone wires locating victims. The flood victims, most dressed in bed clothes were lifted from rooftops. Others were in trees or on car-tops. Pfeiffer brought the helicopter down close and Accamo lowered the basket and began the routine that would repeat itself throughout the night and the following day. When the cabin filled, they would rush to the airport, which was on high ground, and then return to resume the effort.

Not yet light, Pfeiffer took one more trip before changing out with Thometz. He had learned from a rescued husband that his wife, a paralyzed woman, was trapped in their flooded mobile home. He departed immediately with both Accamo and Roulund aboard. They had been flying one pilot and one crewmember at a time, who would relieve each other, to address the fatigue. Factor. But this time two crewmembers were needed. but both went on this trip – one to go down, and get the woman and someone to hoist the basket. Pfeiffer put the helicopter into a hover over the partially submerged and by now floating mobile home. Accamo lowered Roulund in a basket to the roof. Roulund, using an ax he brought with him, chopped a whole in the roof and discovered the paralyzed victim floating on a mattress trapped in the bedroom. Roulund calmed the woman and then carried her in his arms in waist deep muddy water, to the door up front and signaled the helicopter with his flashlight. Accamo lowered the basket and Roulund put the woman in it and Accamo made the hoist. He lowered it again and Roulund came up. On a second occasion, Accamo, with a stretcher, jumped to the roof of a house from the helicopter and an invalid woman was brought aboard.

With daylight Thometz made his first flight and rescued fifteen children from the top floor of a house. He said “We just kept lowering the basket and bringing them up. Then we went back and picked up their six fathers.” The two pilots would make alternate flights throughout the remainder of the day. Pfeiffer, working primarily with ADC Joe Accamo as his hoist operator, Thometz, working primarily with AD2 Vic Roulund as his hoist operator. Thometz thought his most unusual pick-up was from a stepladder.

Flying without co-pilots both Pfeiffer and Thometz grew weary from the strain and the accumulated hours of tension filled flight. When Pfeiffer landed at the San Francisco Air Station on the night of the 24th, his left hand and arm were badly swollen from the constant shifting of the collective and cyclic controls and he limped on his left leg from the ceaseless adjusting for the helicopter torque by pushing on the rudder petals. Both Accamo and Rouland had knees rubbed raw and both had lacerated hands from the constant extracting, lifting and pulling rescued people into the helicopter from the rescue basket.

For their expert airmanship and performance of duty, all four crewmembers were awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross.

Hank transferred to CGAS St, Petersburg. There he flew the PBM’s and the HO4S-3G helicopter. He stated that the Florida area kept the helicopters busy

LCDR Pfiffer retired from the US Coast Guard, July 1, 1960. with the Rank of LCDR with over 24 and ½ years’ service.

The rest of the story:

At the time of the Yuba City flood there was still a debate within the Coast Guard over whether seaplanes or helicopters were better for rescue operations. As we look back now it would seem to be a no contest but in the beginning the helicopters were underpowered, short ranged and weight limited. Amazing helicopter rescues had taken place but it was done with one pilot and the persons rescued one at a time. The visionaries saw the future, others had worked hard and long over the years to make the US Coast Guard the premiere Search and Rescue organization and were averse to the non-proven.

The Korean War began on June 25,1950. The helicopter was used extensively. and capability increased rapidly. Used primarily for search and rescue in the War’s early days, helicopters had become an essential battlefield tool by the conflict’s end. The Sikorsky HO4S-1 with good lifting capabilities and large cabin was well suited for transport or rescue operations The development and capability of the helicopter in a few short years was astounding.

This did not go unnoticed but resistance to the helicopter in certain quarters remained strong. Sometimes events are duly recorded and rest in the historical archives. Sometimes events change the course of History LT. Hank Pfeiffer, flying in the darkness of night, performing rescue after rescue, in Coast Guard HO4S-3G 1305, did just that.

The flood gained national attention and was written about in Look, Life, Newsweek and Time magazines. It made the front page of the New York Times on December 25. Besides the devastation, the fact that it occurred during the Christmas season awakened the empathy of the nation. Resistance to the helicopter within the Coast Guard began to crumble. The HO4S-3G helicopter extended the Coast Guard’s rescue capabilities far beyond what was imagined 15 years prior. Although underpowered by today’s standards it was the first operational helicopter capable of carrying multiple survivors in a cabin and carry heavy loads. The HO4S-3G was the first helicopter to be equipped for night operations and instrument flight.

Shortly after the Yuba City Rescues, the House Appropriations Committee directed the Secretary and Commandant to cause a “complete re-evaluation of all Coast Guard activities, the conduct of which requires the use of aircraft, and present at least preliminary conclusions by December 31, 1956, including recommendations as to kinds of activities requiring aircraft, types of aircraft required, numbers of aircraft required and a program for financing the procurement and eventual replacement of such aircraft as may prove desirable.” In this report was noted the requirement for helicopters. When the re-evaluation began there were 24 helicopters on board. The Committee recommended that the Coast Guard should procure 79 HUS medium range helicopters, 20 HUL light helicopters.

The Coast Guard acquired an initial six HUS-1Gs (H-34s) from Sikorsky in 1959 as a replacement for the HO4S-3G.but they did not prove to be satisfactory. Options were limited. Sikorsky had designed, a single engine, turbine powered, amphibious helicopter designated the S-62. The S–62, designed for commercial use, had features that were desired by the Coast Guard. It floated on an amphibious hull, it had turbine power, had a large main cabin and it was built utilizing proven components. The Coast Guard converted it to a “Rescue Helicopter” it became the HH52A and 99 HH-52 As were purchased.

The HH-52A, with over 15,000 lives saved in its twenty-six years of service, has the honor of having rescued more persons than any other helicopter in the world. This little helicopter, a unique assemblage of proven parts, comfortably behind the cutting edge, performed astounding feats in thousands upon thousands of occasions. It became the international icon for rescue and proved the worth of the helicopter many times over. It had an enormous impact on Coast Guard aviation.

Helicopters have become the primary rescue aircraft of the Coast Guard. It all goes back to a dark night in Yuba City, California on December 24, 1955

Note: The limited description of the flood operations is based upon the Story. “It’s Christmas Daddy” by Barrett. Beard Coast Guard Aviation Association and used with his permission.

John Moseley

CGAA Historian