Here is more information on the first Coast Guard Geographic North Pole (GNP) overflight and what happened to the hard copy records. There wasn’t much to start with as a big deal wasn’t made over it. Public Affairs was not a big deal in those days. Like most people my memory gets worse every year and I am now approaching 89. I was only able to put this together because of a letter to my mother that I sent her shortly after the flight and that is why parts read more like a letter home than the record of an operational event. I realize it is rambling and disjointed but you have to take what you can get.

The C-123s and HU-16s at Air Station Kodiak, AK were replaced with HC-130Hs in 1968. This greatly increased the unit’s long-range capability. Although the Kodiak SAR sector had been extended to the GNP, the capability to adequately cover this area had not been explored. Navigation in the upper Arctic was one obstacle. The new H model C-130s had a Doppler navigation set which greatly assisted navigation in the areas without adequate radio navigation, but didn’t solve the compass problem. The magnetic compass was of little use in the polar region.

I found a book in the Air Station library that described Polar Grid Navigation and studied it along with our assistant engineer, LT George Gaul. Between us, we doped it out and decided we were ready to try it out. I discussed it with the Operations Officer and got his permission to try it out on a Fisheries Patrol. We accomplished the patrol without getting lost but found ourselves off a little at each checkpoint. I relayed this to the Operations Officer and he decided that we needed professional help.

He contacted the Air Force at Eielson AFB and the SAC unit there agreed to send a couple of their navigators down to school us on Polar Grid Navigation. Two Majors by the names of Schoonover and Brown came down to Kodiak and spent a couple of days with the pilots and checked us out on the proper grid system use. We tried another patrol with it and everything worked out OK.

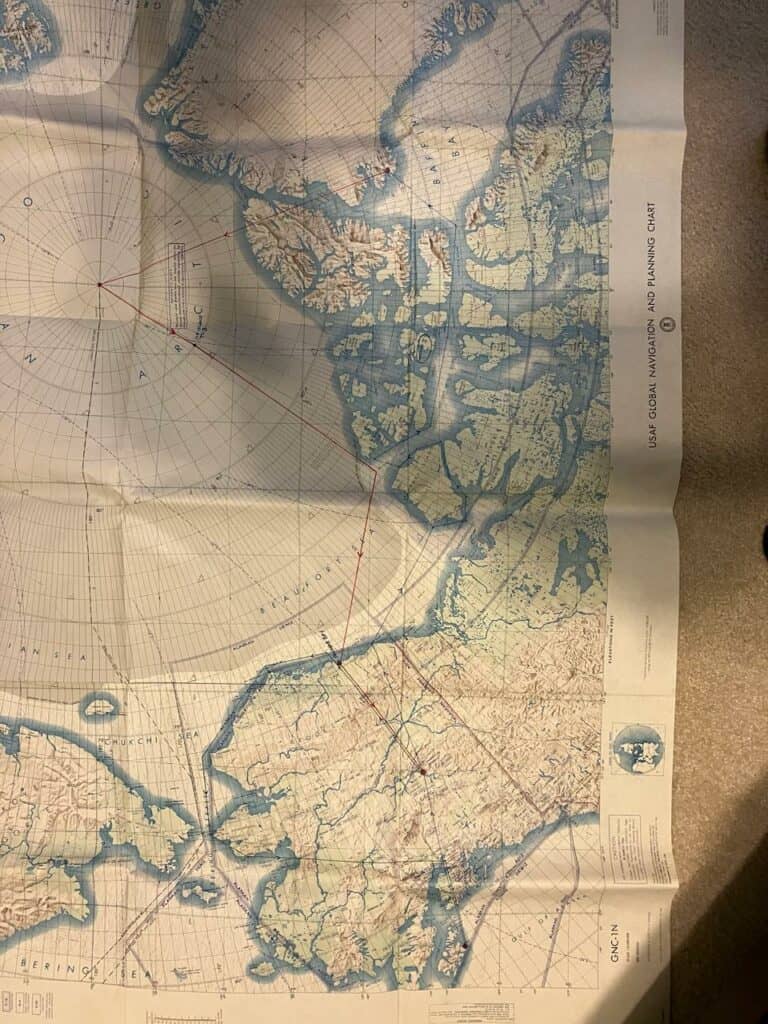

Grid solves the Arctic compass problem by replacing the normal latitude and longitude lines on a chart with an artificial grid. For example, the correct course from the GNP to Point Barrow was approximately 335 degrees on the grid charts we had, not 180 or south. The aircraft then uses a gyroscopic compass adjusted to the grid system. Gyro compasses by themselves can drift off heading so they must be periodically reset by taking a celestial observation to determine the correct heading and then resetting the compass. Taking celestial observations was a real problem on the reconnaissance route because of the amount of cloud cover present. It was necessary at times to climb above the overcast to take an observation and then go back down.

Now that we had a workable system, we were ready to try it out in the far north and determine if we had the capability to cover our SAR responsibilities there. When the SS MANHATTAN came up, we thought it was a good opportunity to put it to the test. The departure morning from Kodiak, the Navy ice observers under LCDR Bill Dehn jumped in and asked to extend the route over the North Pole and down across Ice Island T-3 to check conditions there. I discussed this with the Operations Officer and he referred me to the CO. The CO told me I should only go where the ice observers wanted to go and a polar over flight was rapidly cranked into the plan.

There was a problem with this in that no one ran this past the Seventeenth District. A revised Flight Advisory was never sent and this became a problem. When the message of the actual GNP overflight was received at the District – the Chief of Staff went to the District Commander and adamantly declared that I should receive a court martial. The District Commander overruled him and told him that he thought it was all pretty good. This was told to me later by the District Commander who had been my CO at Kodiak on an earlier tour.

With the Air Station and District hierarchy (except for the Admiral) in a hanging mood the flawless mission completion and proving of this new Arctic operations tool was never acknowledged. There was no citation recommendation or attaboy. No one even said “good job” or asked how it went. It was just ignored. Even with the modern navigation equipment now in use it took 25 years for the feat to be repeated.

Many years ago when RADM Bill Jenkins was the Coast Guard representative at the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, he put out a call for historical items for the Coast Guard part of the museum. I sent him all the original flight plans, messages, news articles, etc. and they evidently disappeared into a black hole and were never seen again. George Krietemeyer looked for the items when he was the representative and found no trace of them at the museum. I suspect the museum didn’t consider the items important enough and trashed them. I do still have my log book and the cryptic entry for May 7, 1969 reads “ICE RECON EIL TO THULE VIA GNP & T3.” I even messed that up as it should read THULE TO EIL.

The GNP overflight idea all started the summer of 1968 when Atlantic Richfield Company struck oil on the North Coast of Alaska at a place called Prudhoe Bay. The oil strike was a big one and most estimates placed it larger than any in the U.S. The problem was how to get the oil from there to a refinery for processing. One way was to build a pipeline to an ice-free port in Southern Alaska or even all the way across Canada to the Midwest U.S. The other was to bring it out in giant icebreaking tanker ships.

The Humble Oil Company converted a super tanker (SS MANHATTAN) to an ice breaker configuration and in cooperation with the Department of Transportation explored the feasibility or running this ship through the Northwest Passage across the top of Alaska and Canada to get the oil out that way. The routes that the MANHATTAN was interested in were from Prudhoe Bay west around Point Barrow and down through the Bering Strait to the west coast of the U, S. and from Prudhoe Bay east through either McClure Strait or Prince of Whales Strait to Viscount Melville Sound, Barrow Strait, Lancaster Sound, Baffin Bay, and south to the east coast of the U.S. The Coast Guard being part of the Department of Transportation then was given the task of ice reconnaissance for the experiment. The U. S. Navy provided additional ice observation expertise with a group headed by LCDR William Dehn, USN.

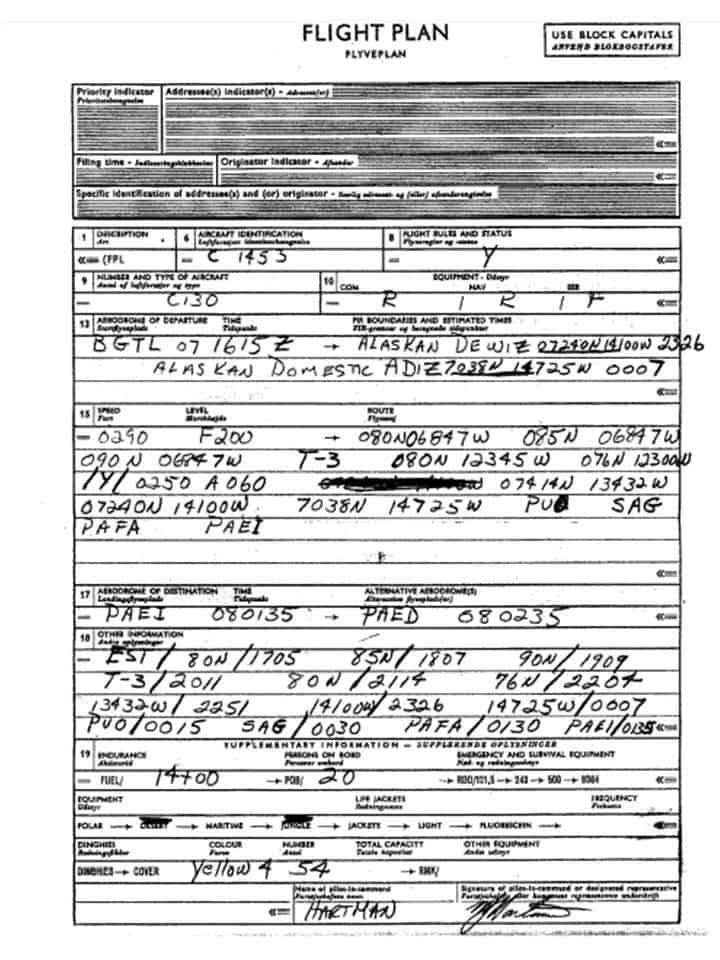

HC-130H CGNR 1453 (LCDR Melvin J. Hartman, Aircraft Commander and LT Lawrence A. Minor, Copilot – full aircrew list below) departed Kodiak on 5 May in the afternoon and flew to Eielson AFB, Fairbanks. At Eielson we planned our trip for the next day, got some sleep and left at 3:00 am the next morning. The weather wasn’t very good and we had a hard time staying under the cloud cover where the ice observers could see the ice to plot its condition. There were only two radio aids to navigation along the entire route so navigation was difficult. We had to keep climbing above the clouds to make celestial observations of the sun to keep track of our position. To complicate things our route took us past the magnetic north pole then located at the southern end of Bathurst Island, so the magnetic compass was useless. We had two very good navigators however (LT Robert W. Mueller & LT Frank Miller) and we arrived at Thule, Greenland right on schedule.

LCDR Melvin J. Hartman AC

LT Larry Minor CP

LT F. W. Miller NAV

LTJG R. W. Mueller NAV

AD1 A. P. Gossage FE

AD1 G. M. Baron SCAN

AT1 T. R. Okestrom RDO

AE1 B. J. Dahl FM

AMC J. C. Vetro LOAD MST

AM1 R. S. Barger SCAN

AT3 A. P. Howland SCAN

We left Thule at noon Thule time on 7 May and flew straight north towards the pole. Other than the ice cap over Greenland and the wild looking mountains on Ellesmere Island there wasn’t much to see. Our last contact with land was the north tip of Ellesmere Island. After that there was nothing but the Arctic ice pack below us. The weather was good and we were able to use the sun to navigate by. At 3:21 pm Eastern Daylight time we flew over the Geographic North Pole and became the first Coast Guard plane to do so. As we crossed over the pole, I made a complete circle around it in 80 seconds. At the pole a complete circle is a trip all the way around the world crossing all meridians.

After the pole we headed south to Ice Island T-3 located at 85 North 126 West. It was a weather station on a large ice island operated by the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory. From there we headed to the entrance to McClure Strait, then to Prudhoe Bay and on to Fairbanks.

We stayed overnight in Fairbanks again and left the next morning on the last leg of the trip. We went back up to Prudhoe Bay and then west to Point Barrow and down through the Bering Strait. We arrived back in Kodiak at 5:00 pm.

It seems odd that this episode was kept so quiet that someone could try to claim the record over 25 years later.

The following year the S.S. MANHATTAN made a successful voyage from the East Coast of the U. S. to Prudhoe Bay and back but the data gathered proved that it would be more economical to build a pipeline to Valdez, Alaska and ship from there. The following information on the MANHATTAN voyage and final disposition was obtained by my research assistant Mr. Google.

The icebreaking tanker MANHATTAN made a historic voyage to test the feasibility of using the Artic Northwest Passage as a year around trade route. Humble Oil & Refining Co., the project sponsor hoped to prove that the Passage can be used by special ships to deliver Arctic oil to U.S. East Coast ports. The cost for this project reached $54-Million. Benefits of an open Polar Sea route included increasing U.S. self-sufficiency in oil. The converted MANHATTAN was well equipped for the task. Even before the modifications, the MANHATTAN was stronger and more powerful than any ship of its type in the world. Built in 1962 in Bethlehem Steels’ shipyard in Quincy, Mass, the MANHATTAN was the largest merchant ship ever to fly the American flag and the largest commercial ship ever constructed in the U.S. It’s 43,000 shaft horsepower power plant is nearly 1-1/2 times more powerful than those on ships twice her size. In addition to size, the MANHATTAN was highly maneuverable, due to twin five-bladed propellers and twin rudders. In short, the MANHATTAN was a one-vessel breed of supertanker, more powerful, and more maneuverable than any similar ship on the seas.

To speed the conversion to an icebreaking tanker, the ship was dry-docked at Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company and cut into four pieces. The 65-foot forward bow was stored at Sun, to be replaced by a new 125-foot icebreaking bow which was built in two sections. The forward piece was built by Bath Iron Works and the after piece was built by Sun Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co. The forward section, including the No.1 cargo tank, was towed to Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company where it was fitted with a heavy 1-1/2″ thick ice belt to protect the ship sides from large floes of ice. The midship section, which included the bridge, was towed to Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company where an ice belt, of steel was also fitted. The stern section remained at Sun to be strengthened internally. While the hull work was being carried on, Sun Ship workers were installing additional quarters, laboratories and electronic gear. When the hull sections were returned, Sun rejoined them, sealed off most of the cargo tanks (which were used for ballast) and then put the ship through river trials. As completed, the MANHATTAN had been lengthened from 940 feet to 1,005 feet, widened by 16 feet to 148 feet, and it weight increased by 9,000 tons.

Accompanying the MANHATTAN, the first commercial vessel to transit the “Top of the World” route, was the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker Westwind and the Canadian icebreaker John A. McDonald. The Westwind was relieved by the icebreaker Northwind, which traveled eastward from the Bering Sea.

On Sept 2, 1969, the S.S. MANHATTAN turned her huge armored bow toward Baffin Island and started encountering her first ice floes at approx. 14 feet thick. The MANHATTAN, cracking off half-acre floes, sailed on without a quiver. When in the McClure strait however, ice 15 to 20 high and sometimes as deep as 100 feet proved too much for the MANHATTAN. Ploughing into thick ice, backing out and going forward again and making very little headway and requiring icebreakers to relieve the pressure on the side of the ship caused a change in direction on Sept. 11th and the MANHATTAN changed course to the Prince of Wales straight, the more normal route for the Passage. On Sept. 14, the prow of the MANHATTAN cracked the last floe at the southern end of Prince of Wales Strait and ahead lay 1,000 miles of open water. Upon reaching Prudhoe Bay, the MANHATTAN took on a ceremonial barrel of oil.

The return trip was completed on November 12, when the tanker sailed into New York Harbor. In spite of its accomplishments, the data acquired during this and a second trip concluding that, at the present time, the use of supertankers to move oil from Prudhoe Bay to the East Coast, is not as economical as a pipeline across Alaska. This study ultimately resulted in Humble joining other oil company’s in building the Trans-Alaska pipeline.

The MANHATTAN returned to New York on 10.30.69. She resumed regular service until 1987. She was driven aground at Yeosu, South Korea on 07.15.87 during the passage of typhoon “Thelma”, refloated on 07.27.87 and sold to Hong Kong interests “as lies”. Re-sold to Chinese Breakers. Left Yeosu in tow 09.01.87 and arrived at breakers yard 09.06.87.

UNRELATED ITEM ON USCG HELICOPTER ARCTIC OPERATIONS

I would also like to offer this observation concerning Polar operations with Coast Guard helicopters. Between the legendary exploits of Dave Gershowitz in 1946 and the 1965 sojourn of Don Bellis, et al, Coast Guard helicopters were operated in the Arctic on Coast Guard icebreakers. In late 1960 or early 1961 the two HUL-IG helicopters based at Elizabeth City and used for illicit liquor still hunting in support of the Revenue Service, were transferred to CGAD Kodiak where they were deployed on the CGC Northwind for operations in the Arctic. I spent the spring of 1960 hunting illicit stills in Kentucky with HUL-IG CGNR 1337 and the fall of 1961, with the same helicopter, on the CGC Northwind operating in the Arctic Ocean above Alaska and Russia.

Mel Hartman