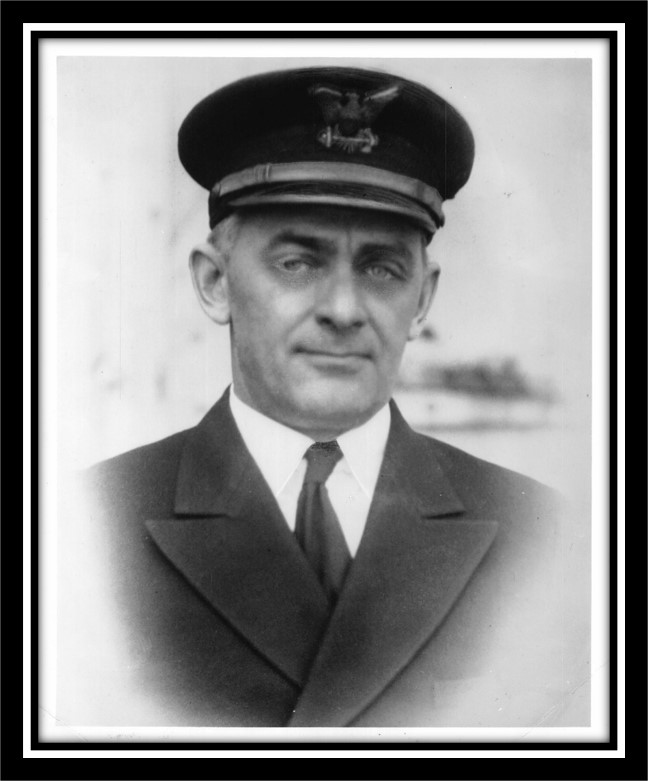

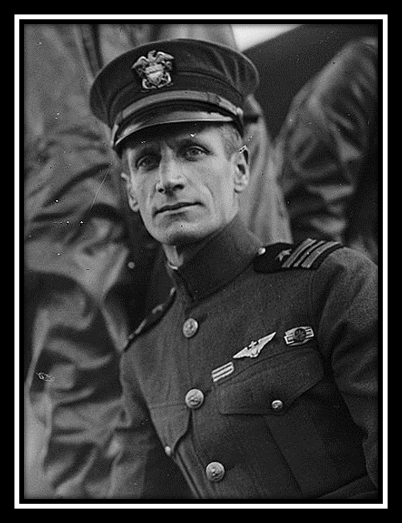

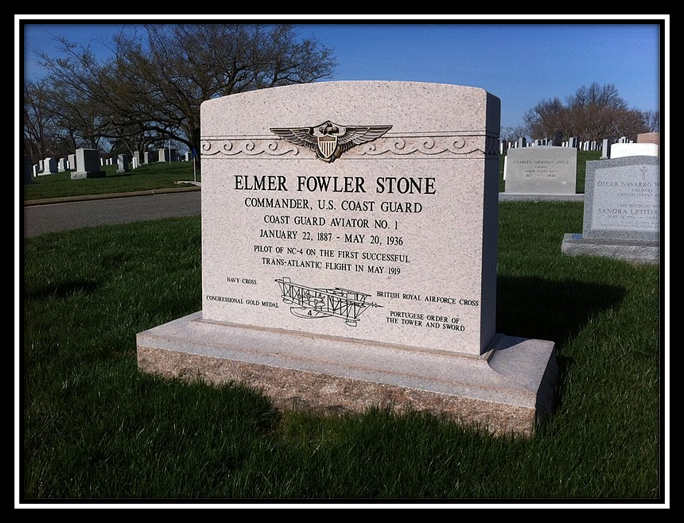

Today we gather, as we do each year to celebrate the life and contributions of a visionary…Coast Guardsman, cutterman, test pilot, aviation pioneer….Elmer “Archie” Stone. His is a fascinating story…one of adventure and daring. Born 135 years ago on 22 January 1887 in Livonia, New York, Stone grew up in Norfolk, Virginia. He joined the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service as a cadet at the Revenue Cutter Service School of Instruction on April 28, 1910.

After graduating with a curriculum in engineering in June, 1913, Stone was commissioned a Third Lieutenant. He served aboard the cutters Onondaga and Itasca…and it is here that we find the genesis of Stone’s love of aviation.

In 1914, Itasca was homeported in Hampton Roads, her mooring next to the Curtiss Flying School. Stone’s imagination was set afire watching the seaplanes fly and maneuver….and remember…war in Europe had stimulated the need for volunteer aviators. The Atlantic Coast Aeronautical Station was also located in Hampton Roads.

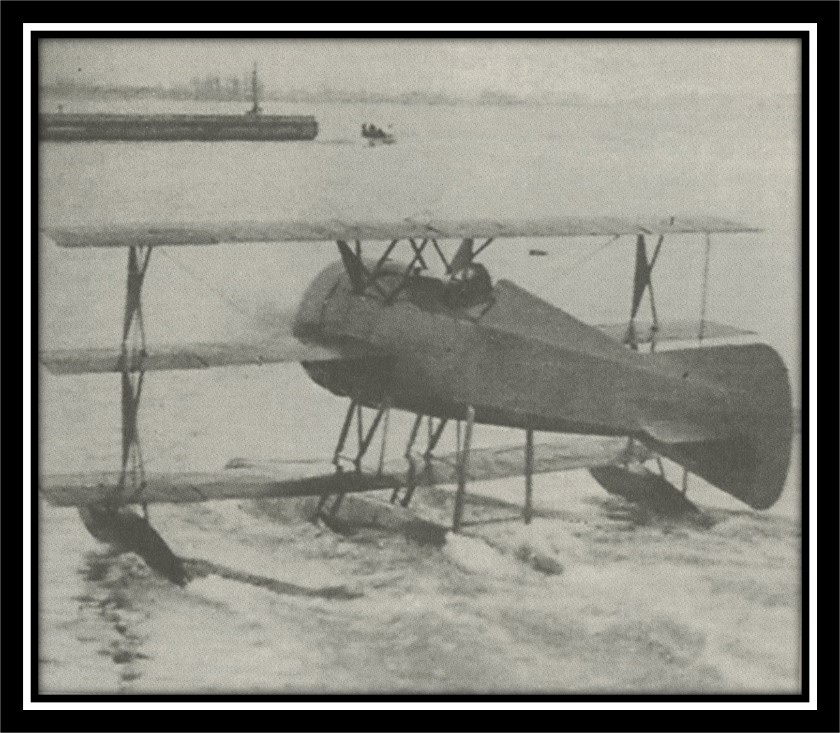

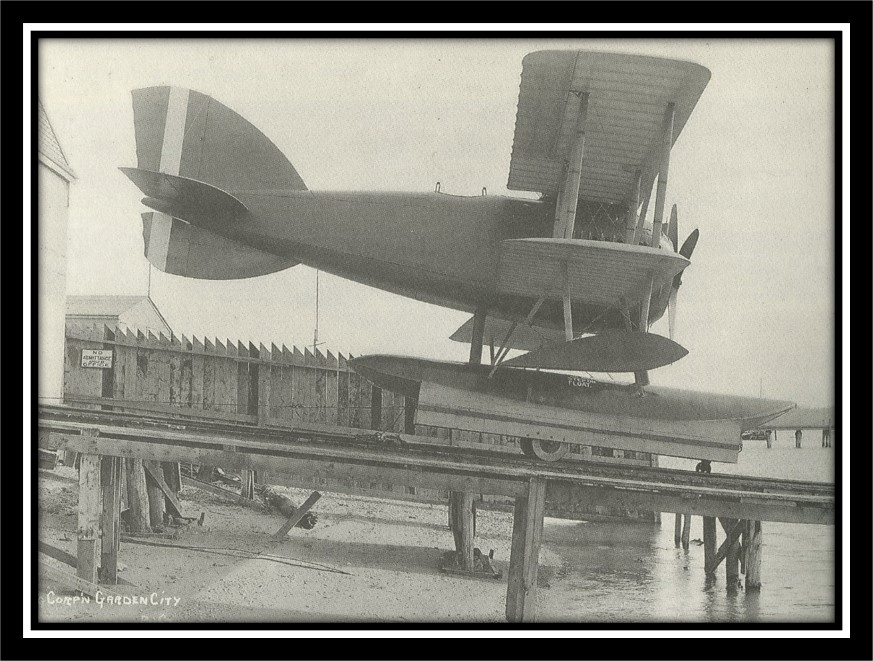

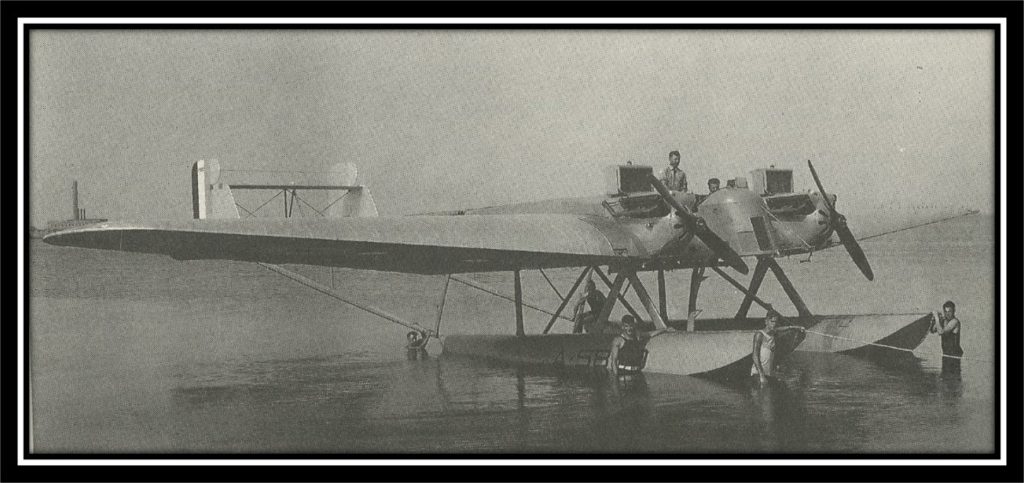

This was a training field for Canadian and American volunteers and Stone befriended many of them. In 1915, encouraged by Captain Ben Chiswell, Stone and Norman Hall met with Thomas Baldwin, who ran the station. They discussed the idea of using aircraft in search operations. In March 1916, Stone was issued orders to test such a concept. Baldwin offered the use of a Curtiss F-type flying boat.

It was so successful that Stone received official “blessing” from Captain-Commandant Bertholf. On 30 March 1916, Elmer Stone was ordered to Naval Air Station Pensacola for flight training.

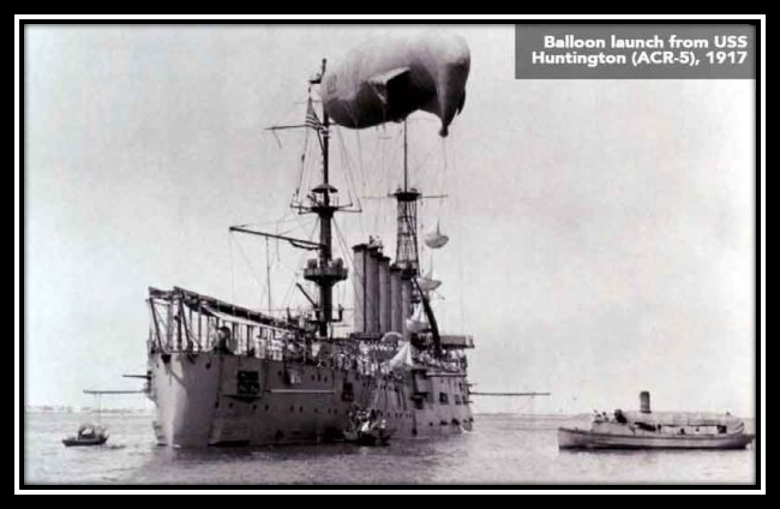

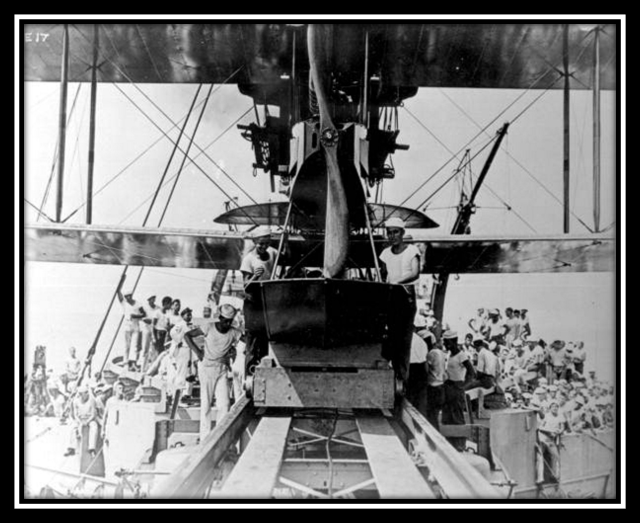

Stone completed flight school on 10 April 1917, naval aviator number 38. Coast Guard aviator Number 1. On 2 July, Stone was assigned to the USS Huntington as a Curtiss R-6 pilot, He was involved in the testing of the catapult …quite an unsuccesfull endeavor as the catapult’s car was generally lost over the side during launch. This was a problem not lost on Stone, and one he would revisit later in his remarkable career.

On 13 October, Stone was ordered to take temporary command of Naval Air Station Rockaway, until the arrival of the designation commanding officer. Stone became the seaplane officer, and spent the next 8 months flying. His natural abilities did not go unnoticed.

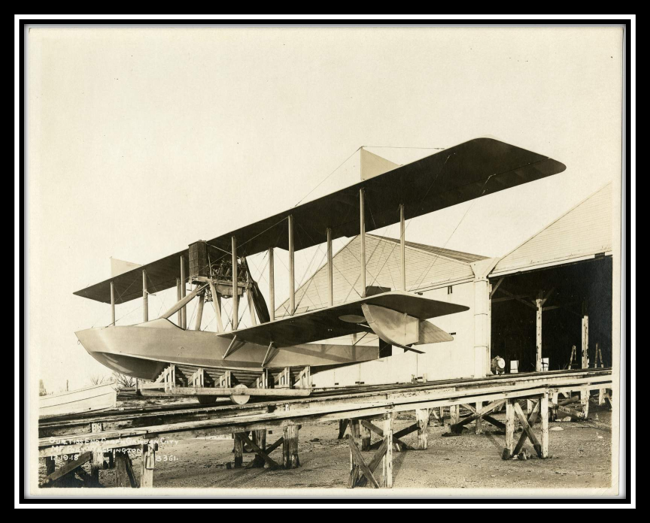

On 15 May 1918, Stone was ordered to the Navy’s Bureau of Construction and Repair, to inspect and test seaplanes. Stone had the opportunity to conduct tests on a number of aircraft….and the life of a test pilot is NOTHING if not interesting.

In 1918 engineering design changes upgraded the Curtiss HS-1 to a new aircraft: the HS-2. When prototype testing was undertaken, Stone was one of the pilots. And after that test 3d Lt Stone recommended additional changes to flight performance for the pilot and operational performance of the aircraft.

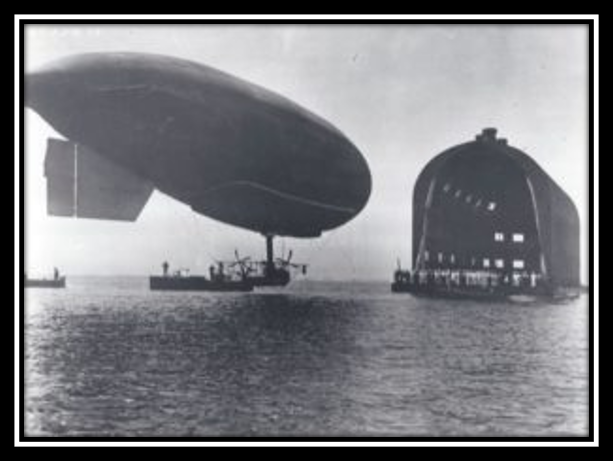

He had stated“the rudder control is very tiring to the pilot.” After testing on the Curtiss Speed Gnome Scout, Stone flew the Curtiss Modernized F boat. Reports from that testing cycle state, “ The boat lands with no shock whatever, even when “pancaked from 8 feet!” After flying a Boeing Seaplane and the Carolina F-boat, stone conducted tests of the Navy’s DN-1 dirigible. During testing of the Gallaudet D-4 light bomber, a propeller tip shattered.

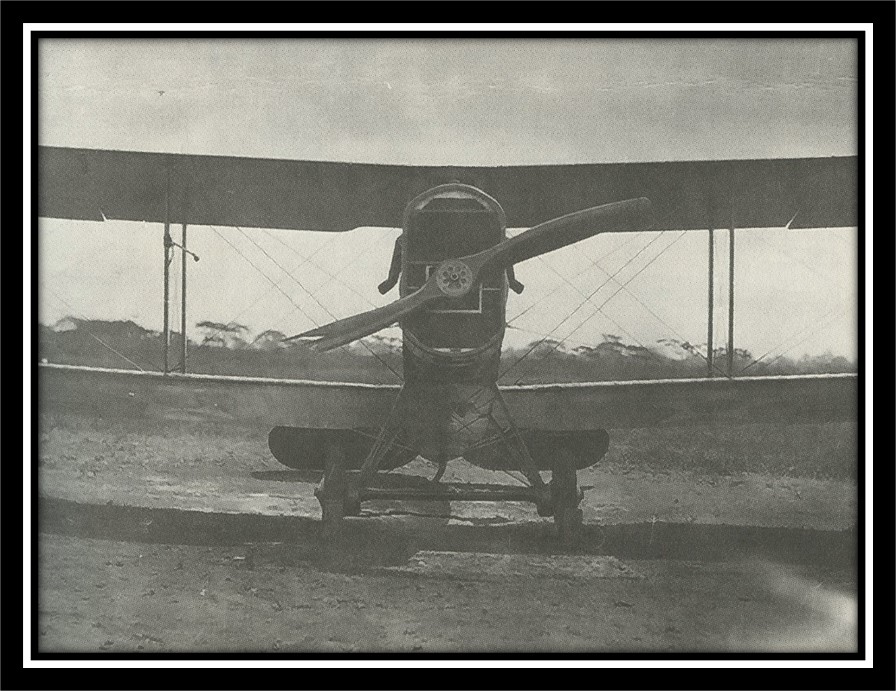

The next challenge was the Huff-Daland HA fight. This is a fascinating aircraft: Liberty twelve cylinder engine, two bladed propeller, two Marlin machine guns mounted over the center of the upper wing, and two Lewis guns aft of the cockpit. Stone was not part of the first test, but was part of the second. His report read, “ Just as the ceiling was reached on one of the climb tests, the motor caught fire. The plane was immediately put in a steep slide slip and brought down from 15,000 feet without accident….The automatic fire extinguisher was not operated, due to the difficulty of reaching the control, and necessity for the pilot to devote most of his attention to maneuvering of the plane.”

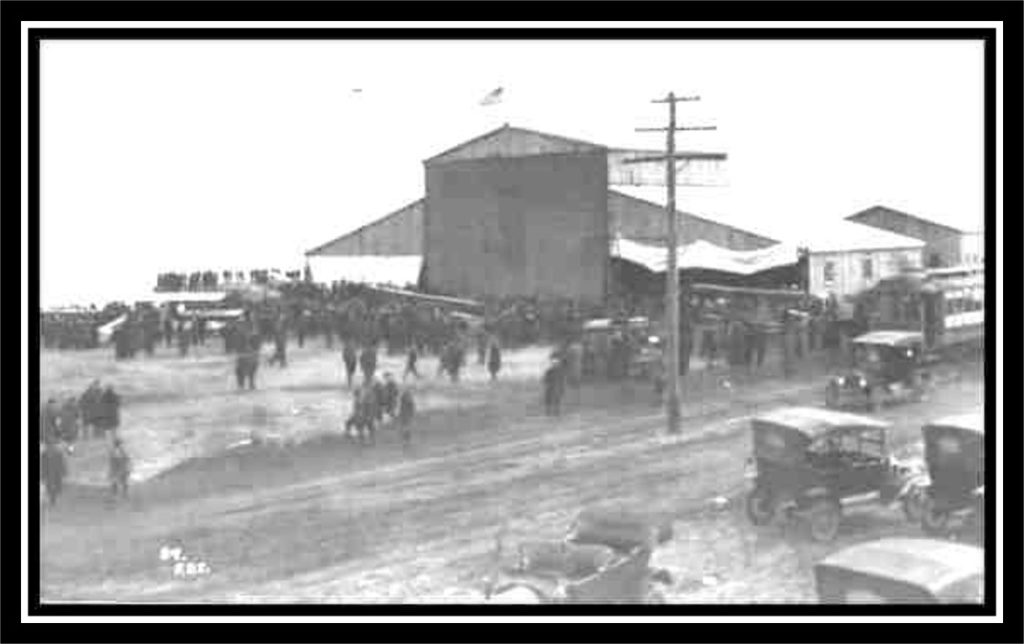

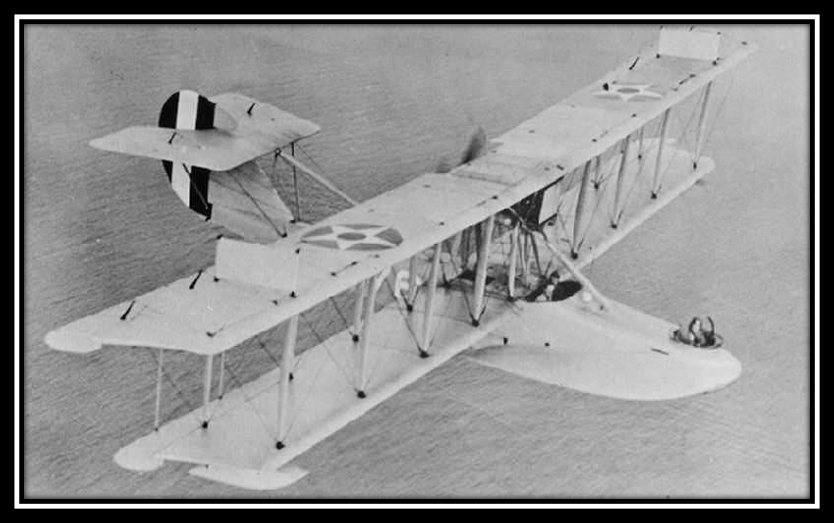

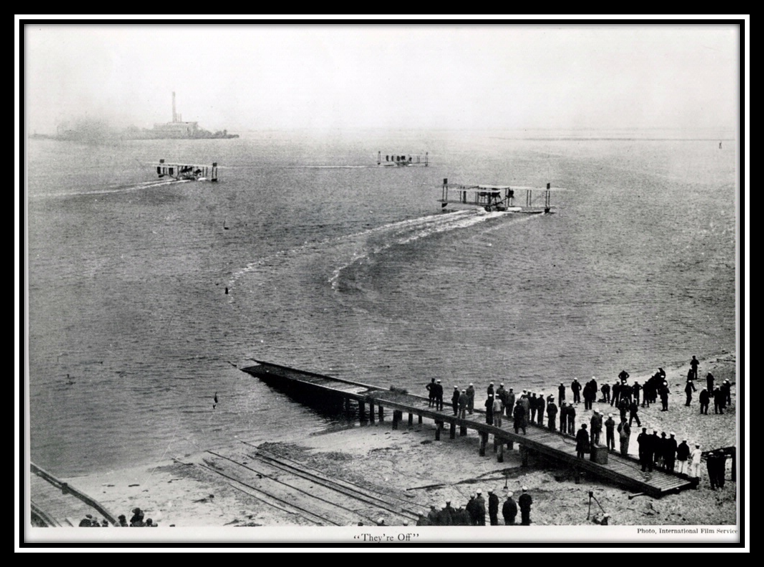

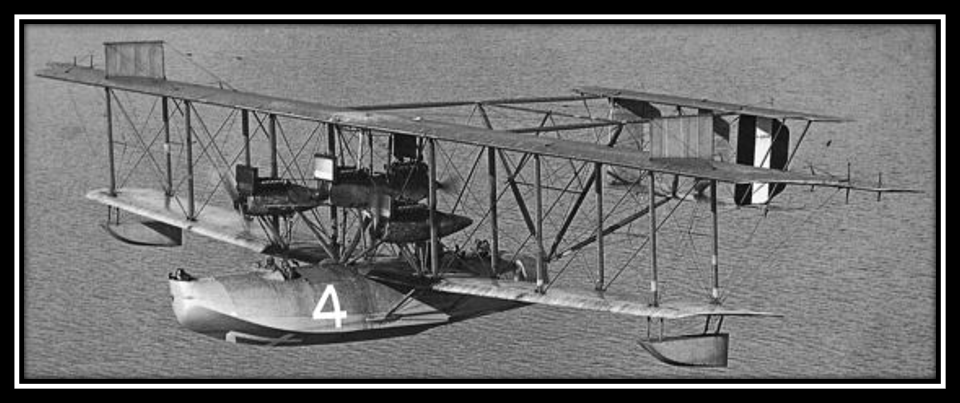

On 21 April, 1919 Elmer Stone was ordered back to Rockaway in preparation for the first transatlantic flight. At 1000 , 8 May 1919, NC-1, 3 and 4 lifted off with little fanfare. (SLIDE-DEPARTURE) Behind the controls of NC-4 was Elmer Stone.

The voyage was not an easy one, and was characterized by mechanical problems and by weather. The NC-4 had flown only once prior to the departure and the leg to Halifax was to serve as the “shakedown’ flight. After passing Cape Cod and over the open sea the NC-4 suffered engine problems. The NC-1 and NC-3 ran into heavy weather enroute. Both decided to land, both hit hard, ending their voyage. There was but one plane left.

There are stories that at one point ,Lieutenant Commander Albert “Putty” Read (SLIDE-READ) wanted to abort the mission. And those stories say that Stone threatened to hit him in the head with a fire extinguisher. True? Don’t know…but it makes for a danged good story! NC-4 was also in bad weather. Read motioned to Stone to take it up and the NC-4 broke out on top at 3200 feet. As they approached the position of the next destroyer the commander gave orders to descend for a visual check. As they entered back into the clouds the aircraft began to buffet and became difficult to fly.

A wing dropped and the aircraft went into a spin. Read shouted for Stone to bring it out of the spin. To bring such a large heavily loaded aircraft out of a spin in clear weather would have been an accomplishment but the NC-4 had reentered solid clouds with zero visibility and to be able to bring it out of a spin with the rudimentary flight instruments then available was an amazing feat, and a testament to Stone’s skill. At 20:01 on May 27, 1919, the NC-4s keel sliced into the waters of the Tagus River. The welcome was tumultuous. A transatlantic flight, the first one, was an accomplished fact!

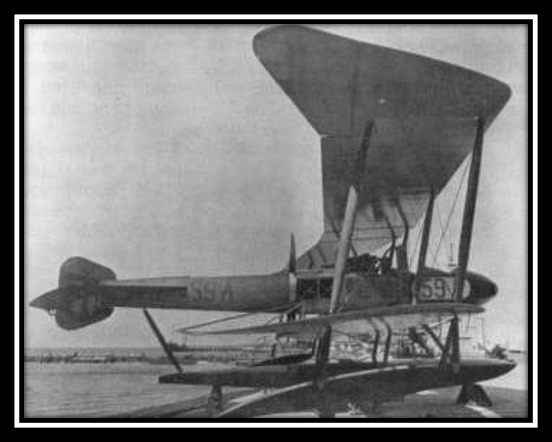

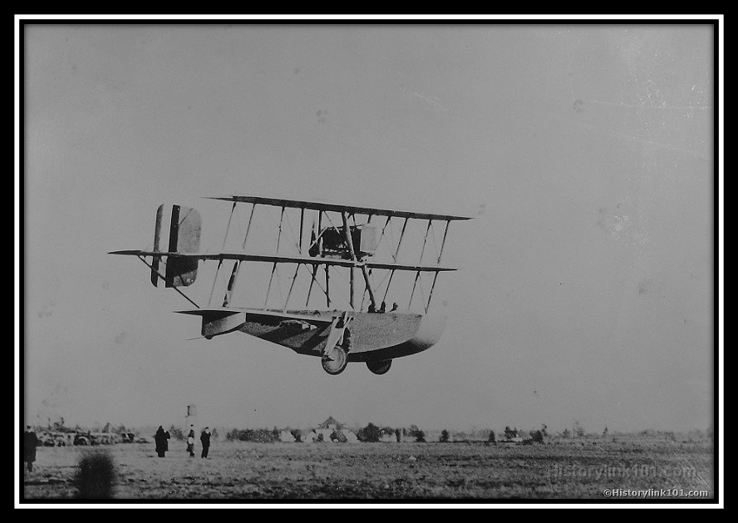

After being lauded for his accomplishment, Stone returned to testing. Of Note? The Sperry Triplane, which Stone reported, “ Unsuccessful in that the plane cannot be taken off the water!” Stone’s notes on testing of the Loening M-81, read, in part, “the plane, fully loaded can apparently only get off in a strong wind and this only after a long run. When once off, it has very little reserve power and a drop

in the engine power causes the plane to settle in the water. It appears to be entirely too heavy for successful flight.” Of the Curtiss CT (SLIDE CURTISS CT) he stated, “Several attempted were made to conduct trials but none were completed owing to the impossibility of keeping the plane in the air more than five or ten minutes without the engines overheating.”

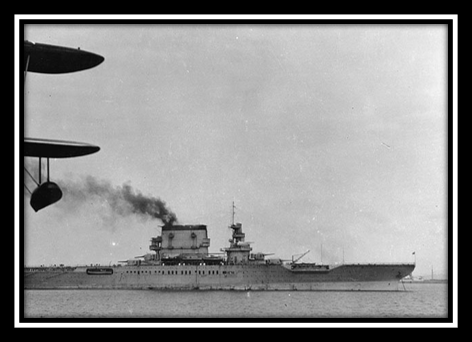

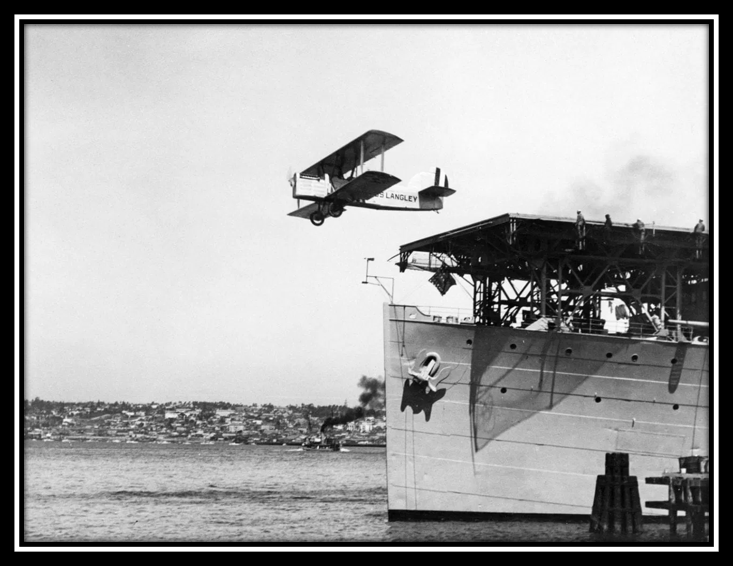

In September 1919, refusing an offered transfer to the Navy with promotion, Stone returned to duty with the Coast Guard. The Navy, however, needed Stone. On 20 November 1919, Stone was ordered to report to the Aviation Division of the Bureau of Construction and Repair to participate the development of the carriers Langley, Saratoga and Lexington.

The coal barge Jupiter was converted to a catapult barge at the Washington Navy Yard for use in “Flying off platforms for shipboard airplanes.” Flying off Jupiter, Stone, once again, experienced problems associated with Pneumatic catapults. The difficulty was in regulating the necessary air pressure. There was little consistency in maintaining thrust. So how could that be solved?

Stone envisioned a gunpowder catapult design…By using three and five inch naval ordnance, propelling thrust could be maintained.

Remember Stone’s experience flying off Huntington? He had designed a hydraulic brake could solve the problem of the carriage flying over the side of a ship…It would be tested in tandem with the gunpowder catapult.

That test catapult was subsequently manufactured and successfully tested. Something of interest? A number of people laid claim to the concept of the powder catapult. Stone and Jensen filed a US Patent application. Amid the controversy, the NAVY JAG ruled that while neither Stone nor Jensen had any rights under any patent issued, Stone had, indeed, “Invented the powder catapult.”

But by 1925, with the need to fight a rum war, and a shortage of midgrade officers, the Coast Guard needed Stone. Commandant Rear Admiral Billard asked he be returned. Rear Admiral William Moffett, commanding the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics, contacted Billard.

He asked that he reconsider his request and allow Stone to continue his efforts. Said Moffett:

I cannot commend too highly the work which Lieutenant Commander Stone has done in this bureau. It is owing to his technical ability, attention to duty and perseverance that the development of the powder catapult has been perfected, made ready for production and issued to the service. Lieutenant Commander Stone is still employed upon catapult work and also on the installation of arresting devices for the new carriers Lexington and Saratoga. This work is of the highest priority at present in the Bureau, and because of its great importance and Stone’s familiarity with it, it is necessary that he should continue in this Bureau.

Moffett agreed to release Stone upon completion of his duties.

Stone was detached from the Navy and returned to the Coast Guard on 21 September, 1926. One month later, Stone became XO of MODOC, then commanded Monaghan, and Cummings before

returning to aviation duty six years later. Six years! But During these years at sea, he studied swell and sea conditions with the purpose of deriving optimal heavy sea landing and takeoff procedures for seaplanes.

Stone served as the senior member of the trial board for new seaplanes being built by General Aviation Manufacturing, and in 1934 was assigned to Douglas Aircraft as an inspector. On 20 December, flying a modified Gruman JF-2, Stone established a world speed record for a single engine amphibian. (SLIDE-STONE SPEED RECORD)

Commander Stone’s last duty was as the commanding officer of the Air Patrol Detachment in San Diego until his untimely death on 20 May 1936.

And what of Stone’s legacy? Courage, backbone, grit, determination, tenacity, persistence, daring, forthrightness. His jealous Coast Guard Academy classmates belittled his achievement as pilot of the NC-4. Yet, his experience as a test pilot was unrivaled and he made several record breaking flights. His uncanny foresight anqualities of leadership, made him respected and beloved by all who served under him. Not only was he talented but dedicated to an organization that did not always return the respect he earned. He was considered something of an eccentric…and was, at times, many times, at odd with leadership, and disliked by leadership… But Stone is the foundation of Coast Guard aviation…His career had far-reaching effects on the development of naval aviation. Historian Captain Robert Workman looked to aviation visionaries…men like Glenn Curtiss, Eddie Rickenbacker, Jimmy Doolittle and Marc Mitscher…and said “perhaps the most outstanding of them was Elmer Stone.” I have spoken with some of you about this….your responses? “He was the first of our breed.” “He gave us wings!” “Damn! What he did!” “All of those who wear Coast Guard wings carry a part of Elmer Stone.” Today we honor him….the first of THIS breed…his legacy is part of you. Carry that with great pride!