One of a Kind

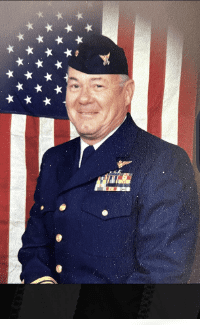

LCDR James Casey Quinn USCG

Casey had a captivating smile. He met everyone in a disarming way; likeable; .and as you got to know him, the bonding took place.

Casey was born in Sparta, Michigan on Sunday, February 1, 1931. He spent his younger years in Escanaba, Michigan and relocated to Dallas, Texas in 1944. He graduated from Crozier Tech high school and attended North Texas State University from 1949 – 1952 while working for Texas Instruments. The Korean War was taking place and Casey, realizing a boyhood dream to fly aircraft, applied for and was accepted in the Naval Aviation Flight Training Program. and earned his wings.

Casey spent his early days flying Navy ASW Missions off Aircraft Carriers and the Naval Training Command at NAAS Whiting Field, located a little bit northeast of Pensacola. Florida.

If you are old enough to have passed through NAAS Whiting Field in the early 1960’s you might recall a Dixieland Jazz band named the Slow Roll Seven. Casey’s instrument (though he admits to not being a musician), was the “gut bucket,” It consisted of a galvanized washtub strung with a single wire-clothesline stretched on a shovel-handle neck. Casey’s strumming was more entertaining to watch than what the almost single-octave instrument likely added to the ensemble.

In early 1965 Casey made application to become a Coastie. His request was excepted and he spent the next two plus years flying Goats (UF Grumman Albatross amphibians) out of the Coast Guard Air Station Miami. While he was at Miami, a request was made by Coast Guard Headquarters for UF qualified pilots to supplement the Air Force Search and Rescue efforts in Vietnam. Casey volunteered, was accepted, but the aircraft type was changed to the C-130P. Casey was off to the Advanced Flying Course for the C-130 and the C-130P. The C-130P was an aerial refueler and a Command Control aircraft. In June of 1968 he reported to the 31st ARRS, Clark AFB, Republic of the Philippines, arriving 3 June 1968. The mission was standard fixed wing SAR. Casey preferred the C-130P operation and requested, at the local level, a transfer to the 39th ARRS, based at Tuy Hoa, Vietnam. Casey’s request was approved.

During the War in Southeast Asia, when an American aircraft was shot down over hostile territory; the elapsed time between shoot down and attempted rescue was critical. The shorter the time interval between shoot down and attempted rescue; the better the chance was for a successful rescue. Records indicate that the percentage of successful rescues dropped rapidly after two hours. To reduce response time following a shoot-down, the Aerospace Rescue & Recovery Service designated four helicopter refueling orbits. Two were over the Laotian-North Vietnamese border, one was located over central Laos, and the fourth was east, over the Gulf of Tonkin. HC-130P crews established holding patterns prior to US airstrikes to enable immediate support for rescue operations. Aerial refueling capabilities greatly enhanced the rescue helicopters capabilities. In addition to refueling operations, HC-130Ps, (call sign “Crown” and later “King”) carried mission coordinators whose job was to assemble and manage the Search and Rescue Task Force (SARTF) of helicopters, H3 or H53, (call sign Jolly) for recovery and fixed wing A-1 aircraft, (call sign Sandy), for protection and ground fire suppression They also acted as a communication link between rescue forces and higher echelons.

On December 27, 1969 Casey, out of Toy Hoa, was on a Laos orbit and Rob Ritchie USCG, was in a H3 Jolly Green helicopter, looking for Nail-53, Captain RR Russell, a downed OV-10 pilot. There was no hostile fire and the thick jungle canopy was making it difficult to locate the survivor but Ritchie knew him to be somewhere on the west slope of the valley. Radio contact was established. Nail 53 could hear the helicopter but he could not see it. After further conversation Ritchie felt he had the pilot fairly well located and he lowered the penetrator. (a recue hoist) At this point radio contact was lost. He left the penetrator down as it was routine procedure for a survivor on the penetrator to signal the was ready to be pulled up by shaking the cable. After a reasonable period of time the penetrator was raised and Ritchie moved to another spot, sending it down again. This continued but Nail 53 did not respond. The low fuel warning lights came on and Ritchie informed Casey that he would need fuel. After a few more minutes without a nibble, he told his flight engineer to retract the penetrator because they had to get out of there. The flight engineer responded that it felt like someone was near the penetrator. Shortly thereafter came the pull up signal and Captain Russell was brought aboard. When the low fuel lights came on in an HH-3 a pilot had 15 to 20 minutes of fuel left. Five minutes had gone by since the initial warning. It took additional time to reel in 210 feet of cable and get the survivor inside. Ritchie alerted Casey that his situation was critical.

Under a full power surge Ritchie commenced his climb. Suddenly the adrenaline flowed as something dark and massive appeared below him. It was a HC-130P with drogues streaming. Casey, monitoring the situation, had left orbit and came up under the Jolly Green before he cleared the ridge line of the compact valley. Amazing as this was, Ritchie still had to put his fuel probe into a skittish basket. He had to overtake the C-130P with enough rate of closure to seat the probe solidly with at least 160 foot-pounds of force. Charge in too fast and you run the risk of cutting the fueling line with the rotor blades. In addition, when the helicopter accelerates the nose dips. When it slows the nose rises. To hit the basket in this situation with the number of foot pounds required, a sweeping of the probe in an arc, down and forwards into the receptacle was needed. Rob Ritchie hit it on the first try. They climbed out as one.

The coordination, dexterity and the marked degree of flying skill on the part of both pilots was exceptional. While Rob and crew would be credited for rescuing one, they all felt Casey and his crew should be credited with the rescue of five, made possible by bending a few rules.

On 28 January,1970, a F-105G Wild Weasel, over North Vietnam was shot down while making a run on a surface to air missile (SAM) site, both crewmembers ejected satisfactorily. One was seen on the ground, evading, by an A1 Sandy and a major helicopter rescue effort started immediately.

Casey launched for the “Seabird” rescue to assist “King 2.” He was to rendezvous with two flights of “Jolly Green Giants” rescue helicopters. Two were HH-3E’s, call signs “Jolly 09” and “19.” Four were the larger HH53Bs, call signs “Jolly 70,” “77” and “Jolly 71,” “72.” Accompanying the helicopters were four A-1Js, call signs, “Sandy 3,” “4,” “5” and “6.”. Jim Jinks (Sandy 4) said the taskforce began helicopter fueling in a holding pattern on the Laotian border. Shortly thereafter, people started yelling “MIGs and Jolly 71 disappeared in smoke. It had been hit by a missile fired by one of apparently two MIGs that passed through the holding formation. Bender said it was chaos after that. King 03 dropped his tanks and headed west into the weeds (actually they were extended fueling drogues that tore off in Casey’s descent) and the now disconnected refueling Jolly’s did the same. It is believed there were two Migs that made one pass through the helicopter holding formation and flew to the north with one returning.

Casey was doing a “check-in” with the scattered group when Jolly 72 saw a MIG -21 an estimated two minutes after the first strike. The deadly fighter charged at the now scattered and diving gaggle with the obvious target, the fat-lumbering C-130. Jolly 72’s rear and starboard side gunners got shots off at the MIG as it passed, heading toward the C-130. The elapsed time indicated that this was a second MIG. Casey’s crewman spotted it coming fast from their 5 o’clock position and Casey immediately descended into a deep ravine. (Note: The mountain peaks reached to 7,500 feet with the ridgeline running generally north and south with steep ridges and valleys below).

Casey flew the the Hercules in unpredictable, erratic turns at changing altitudes between the steep ridges. He was flying the aircraft to the extreme to avoid a missile lock on. At one time he saw bursts in the karst ahead and below his aircraft’s nose that was cannon fire from the MIG. But he was too busy to dwell on this, hustling that lumbering transport out of harm’s way. Minutes later the C-130 emerged from the ravine alone. The MIG had crashed.

The reader may wonder how a four-engine transport could escape the high performance MIG-21.

- The C-130 was designed to be maneuverable. A low level speed up to 260kts with a stall speed of 100kts and a maximum angle of bank of 60 degrees. However, bank angle was a gravity limitation and could be exceeded if level flight was not maintained.

- The MIG 21 was a very good high speed delta wing, high altitude interceptor. The delta wing, was excellent for a fast-climbing interceptor, however, any form of turning combat led to a rapid loss of speed. The MIG’s situation was made worse by the poor placement of the internal fuel tanks ahead of the center of gravity. As the internal fuel was consumed, the center of gravity would shift rearward beyond acceptable parameters. This had the effect of making the MIG’ unstable to the point of being difficult to control.

The MIG crashed into the side of the mountain.

Note:

The pilot the MIG 21 that shot down Jolly 71 was Vu Ngoc Dinh, a North Vilamere fighter pilot Ace of the Vietnamese Peoples Air Force ,921st Regiment. The pilot that crashed while attempting to shoot down Casey was Pham Dinh Tuan of the Vietnamese Peoples Air Force,921st Regiment.

Casey flew 247 combat missions, and was awarded eight Air Medals and a Distinguished Flying Cross. A unit Commendation and Letters of Commendation.

Upon his return to “the States”, Casey checked in at San Francisco and went to helicopter school. His last duty station was the Coast Guard Institute in Oklahoma City. He retired in August of 1975. His daughter Kathleen told me that after retirement he went to Independence Kansas where a buddy of his lived. He got involved in a number of different things that worked out well. Most of the kids had moved to California and when Mom and Dad got tired of the cold winters they also moved to California. He had a car business while in California. Mom passed away and Dad decided he wanted to move to Texas. We bought Sixty Acres and he lived his life out here happy.

Casey made his “Last Flight” on June 17, 2021. He spent a lifetime passing it forward, with many a good yarn and a multitude of good wishes and smiles left behind.

Coast Guard Aviation Association

Barrett Thomas Beard

John “Bear” Moseley

James C. Quinn, interviews and correspondence with author, 2004

40th ARRS History

Tom Frischman Interview Series 2004

Jim Bender Skyraider Tape Skyraider Organization

Taskforce Megaric SSGT William Shinn

Tom Beard Series of discussions Jun – July 2021

Dick Butchka, correspondence with author, December 2004

Rob Ritchie, Correspondence with author Series 2004

Kathleen Quinn correspondence with the author Jun July 2021

Istvan, Air War Over North Viet Nam