by Larry L French AT2 (USCG 1966-1970)

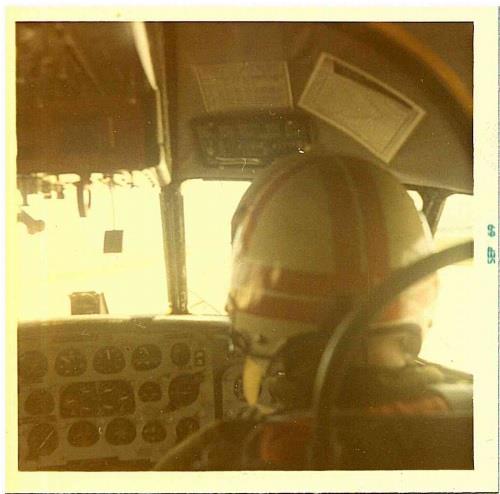

Miami Air Station was known as the “Busiest Air Sea Rescue in the World.” Miami Air had a lot of different aircraft, including; C-123, C-130, HH-52A’s, and HU-16E’s. Consequently, this Air Station covered a lot of territory and fulfilled many diverse operations. Below are some of the routine adventures and challenges these crews faced every day.

One mission that got very little acknowledgement was the reconnaissance flights off of Cape Canaveral, Florida (or more recently referred to a Kennedy Space Center). In the mid 60’s and early 70’s, whenever there was preparation for a rocket launch, the coast line was crawling with huge “fishing” vessels. Our job was to find out who they were and get some idea of what they were up to. We would fly our HU-16 over the “trawlers” that patrolled up and down the Florida coastline. Interestingly, our crew included a Navy photographer assigned to our flight with his 35 mm camera. He was strapped in the back hatch of the plane with a harness. The pilots would make slow and low, sweeping runs over the trawlers, (most of them Russian). This would allow the photographer to hang out the hatch and take a lot of photos. These ships were equipped with huge domes on the decks – hiding their radar and other electronic detection equipment. Our job was to record all the vital information; the direction they were travelling, their speed, the size of the ship, country of origin and other significant markings or details.

Another regular mission was the routine daily flights; the “Green Patrol” or the “Red Patrol”. These were 8- and 10-hours searches to patrol the waters and islands between Key West, FL and Cuba. Looking for Cuban refugees made this part of our flights the most meaningful of all. It was not uncommon to find Cubans attempting to flee Cuba on almost anything that would float (see picture of truck with flotation tanks). Also, we would find people stranded on these little barren and isolated islands. Our job was to notify Air Station Miami that we had located refugees. We would have to encrypt our messages to include the location, the number of people and other vital info. If for some reason we were unable to encrypt the information, the Cuban government would intercept our message. Very shortly afterwards, a Cuban cutter would come out, apprehend them and take them back to Cuba.

Most people that are familiar with the Cold War and the U.S. and Cuban tensions in the 60’s and 70’s understand why it was not safe to fly too near Cuba. On one of our searches in that area, we were surprised and puzzled to see this enormous island right in front of us. That’s when we discovered two things; our gyro had become inoperative and we were flying in the wrong direction and the big island … it was Cuba! Fortunately, we were able to make a U-turn and get out of harm’s way without an incident.

The mainstay of our flights was ships and boats and people in distress. We would generally fly 8 or more hours in a search grid pattern in an effort to locate something generally pretty small in a huge body of water. After several hours of staring at the open sea with nothing but greenish-blue water and silvery-whitecaps, our eyes would glaze over. We would rotate shifts taking “lookout” from the back hatches of the plane. Although sea search and rescue is exciting, there are some long, boring aspects of this work also.

Having routine flight training was a normal part of Semper Paratus, “Always Ready.” Everyone in aviation in South Florida knew about the air strip in the Everglades or the airport that never took off. This airstrip was a great place where our pilots would practice a lot of touch and go’s. Touch-and-go essentially joins two maneuvers into one – the aircraft lands on the runway, then accelerates and takes off again. To add to the excitement of this exercise, we occasionally experience the “thrill” of having the plane porpoising down the runway. Practice makes perfect!

The HU16’s were designed to land and takeoff from water but this could be very risky in the open ocean. If the winds picked up and the seas got choppy, that would make it tough to get up to airspeed to lift off the water and then you were in a lot of trouble; so rarely did we land in the open seas. Most of our water landings training were in Key Biscayne, FL where the waters were pretty well protected from high winds and heavy seas. Any of the crew that flew in these planes can remember these water takeoffs. The plane would begin to vibrate as it was skimming across the surface of the water, trying to get up to air speed in order to lift off.

Our rescue flights would take off, day or night, 24-7, 365 days a year. Often the HU-16 would accompany a helicopter (HH-52) to the distress site to assist in the rescue. Once we located the vessel in distressed, we would often make radio contact and assess the critical nature of the vessel’s situation. We generally had a couple of immediate interventions we could make. (This was a time before the utilization of Rescue Swimmers had started.) In some incidences we would provide a flotation device; in others we might drop a sump-pump; and or have a CG Cutter deployed to the incident. The plane carried a gas-powered sump-pump in a sealed container (about the size of a half of a fifty-gallon drum). When dropping these devices, some preparations were needed, i.e. measuring wind direction and speed. The canister had a long, bright orange ski rope attached. The goal was to drop the pump safely and to ensure the rope went across the boat so the pump could be retrieved. Unfortunately, it didn’t always go completely as planned. You can imagine the surprise when the pump landed just a little too close! Beside frantically bailing water, the crew on the boat really had something to cuss about.

At the time we were flying these various missions, I had no idea of what an honor it was to be working with this group of men. Being on flight status we did get “hazardous duty” pay but we weren’t there for the money. We were doing our part of serving and protecting our country.