The story of

CDR Lonnie L Mixon USCG

John Bear Moseley, CGAA Historian

Lonnie was born January 29, 1933 in Mobile, Alabama and grew up there. He graduated from McGill Institute High School in 1951. Lonnie said that in his senior year a Cadet from the USCG Academy made a presentation about the Coast Guard. It covered Coast Guard duties and operations. Lonnie said being an avid reader of “Don Winslow” comic strips, he thought the presentation was outstanding. After graduation he enrolled and attended Spring Hill College. During the first quarter the idea of joining the Coast Guard became progressively more attractive.

On December 18, 1951 Lonnie joined the Coast Guard and Christmas that year was spent at the Coast Guard Training Center Alameda, California. Upon Completion of “Boot Camp” at Alameda, he was assigned to the CG Cutter Perseus and one month later was ordered to the U S Navy Fleet Sonar School, San Diego, California.

Upon Completion of Sonar School Lonnie was stationed aboard CG83-320 in San Pedro, Ca. The primary duty was to identify every merchant ship that entered the harbor and provide search and rescue between the California coast and Catalina Island. This was during the period of the Korean War and the Coast Guard was specifically called upon to take a leading role in port security, maritime inspection and safety, search and rescue, and patrolling ocean stations in war zones. The Ocean Station ships provide weather information, navigation assistance for aircraft and search and rescue.

In 1953 Lonnie transferred to the Coast Guard Cutter Pontchartrain based out of Long Beach California with primary mission was Ocean Station “Uncle” providing weather. and navigation aid to aircraft flying between the United states mainland and Hawaii. When Lonnie reported aboard the Pontchartrain, he was a Sonarman (SO3), a Third-Class Petty Officer. He was promoted to SO2 in December 1953 and promoted to SO1 in September 1954. The significance is that Enlisted promotions in the Coast Guard are merit based. Members take an eligibility exam for each promotion. Points are awarded based on the results of the exam. Vacancies are filled and promotions are made based on the individuals. Lonnie was promoted to SO1 (E6) in the short time of 2 years and 9 months. Very unusual and a testament to dedication and performance.

Lonnie’s first Enlistment was up. He reenlisted in March and reported to the CGC Cahoone in Galveston Texas. The primary duty was Search and Rescue and the Campeche Patrol. The Patrol in the Campeche Gulf, part of the Gulf of Mexico, provided Search and Rescue assistance and to prevent incidents with Mexico over claims that the United States shrimp fishing boats were violating Mexican Waters, September found Lonnie on the CGC Sebago out of Mobile Alabama, with the same duties as the CGC Cahoone.

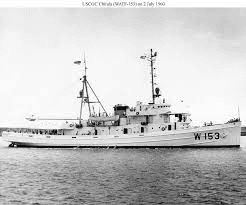

Lonnie applied for OCS and was accepted. In October Lonnie was Promoted to E7, Chief Petty Officer and Commissioned as an Ensign in the USCG. He was ordered to the CGC Chilula at Morehead City, North Carolina and served as a deck officer,

Lonnie said that in the winter of 1959 he was on a Search and Rescue case off the coast of North Carolina. The weather was horrible; cold winds and heavy seas. He said just prior to dark. they received a call from a Coast Guard search aircraft requesting they relay to Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City that they were leaving the search area due to poor search conditions and they would be landing in 35 minutes. He said that that got his attention. The CGC Chilula was to depart the scene also and it would be the following afternoon before they got back to Motorhead City. Lonnie said he had been thinking about aviation and that clinched it. The following week he applied for aviation. He was on the brink of being too old but made it.

Lonnie was promoted to LTJG in June of 1960 and reported to NAS Pensacola, Florida for flight training, He finished his training At NAS Corpus Christi, Texas on July 1, 1961 and received his wings and was designated Coast Guard Aviator #878… His first Duty Station was Coast Guard Air Station (CGAS) Brooklyn.

In July of 1963 he was transferred TAD to CGAS Miami. This was during the Cuban Missile crisis. In October 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union came to the brink of nuclear war over the placement of Soviet missiles in Cuba. The United States armed forces were at their highest state of readiness ever and although not known at the time, Soviet field commanders in Cuba were prepared to use battlefield nuclear weapons to defend the island if it was invaded. For 13 tense days, a fragile peace hung by only a thread as the United States instituted a naval blockade of Cuba to turn back Soviet ships. The crisis was ended when the Soviet Union agreed in a secret negotiation to remove its nuclear weapons from Cuba in exchange for a U.S. agreement to remove its nuclear weapons from Turkey six months later.

During the next very tense days, all options, including the invasion of Cuba were evaluated. The final decision was to impose a U.S. Naval “quarantine” of Cuba. (The word “blockade” was not used because it would be considered an act of war). President Kennedy said the missiles sites must be removed and he was prepared to use force if necessary.

Air Station Miami at Dinner Key, was immediately supplemented with additional HU-16E aircraft, crew members and maintenance personnel from other air stations throughout the Coast Guard. The patrol zone was broken down into patrol areas and designated as Red – Green – and yellow patrols. The patrol surveillance flights were 5-8 hours long and there were usually 2-3 aircraft on these patrols. Pictures were taken of all vessels and all surveillance information was forwarded to intelligence agencies. It was a 24 hour a day operation. It is important to point out that during this period that the Air Station Miami retained the responsibility for Search and Rescue operations.

On November 21: Just over a month after the crisis began, The President terminated the quarantine when Khrushchev agreed, after several weeks of tense negotiations at the UN, to withdraw Soviet IL-28 nuclear bombers from Cuba. However, the Coast Guard Patrols continued at the end of the missile crisis as Coast Guard aircraft continued to monitor all ships in bound to Cuba. Rescue continued to increase. operations related to Cuban immigration which was not encumbered at the time. .. The number of people leaving Cuba would increase steadily over the next several years using any means available reaching a climax when Castro allowed well over 3000 people to leave the port of Camarioco. It also became apparent that the water only facilities at Dinner Key were not capable of supporting the Coast Guard mission and the air station moved to Opa-Locka in 1965. Lonnie’s transfer to Miami was made permanent in September 1963.

In October 1963, Lonnie was ordered to Helicopter Training at NAS Ellyson Field on Pensacola, FL. He completed training on December 30, 1963. He was designated Coast Guard Helicopter Pilot #453.As was common at the time, Lonnie flew both Fixed wing and rotary wing aircraft. From January 1964 through April 1966, he flew the HO4S, HH-52 helicopters and the HU-16E Albatross fixed wing amphibian.

Lonnie went to Detroit in May of 1996 as part of the group that established Coast Guard Air Station (CGAS) Detroit located at Selfridge AFB. Lonnie, a “plank Owner” was the Operations Officer. The original complement was ten aviators and twenty-nine enlisted personnel, equipped with three Sikorsky HH-52A amphibious helicopters, quickly became an integral part of the Coast Guard’s National Search and Rescue (SAR) effort and the aviation hub for the Ninth Coast Guard District, headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio. Detroit proved to be a good location. Between 1 July and 1 December LT. Mixon, as aircraft Commander, flew six rescue missions of note. The most difficult was the rescue of eight crew members off the German MV Nordmeer.

On November 29, the winds began to build from the northwest. A blizzard with 70 mph winds reached the Nordmeer. The Nordmeer sent out a SOS. and the Steamer John A. Kling responded. The waves made it impossible for the Ling to render any assistance. The Coast Guard Cutter Mackinaw, also in the area responded launch a 15-man inflatable life raft and attempted to rescue the Nordmeer but twice was turned back. Coast Guard Air Station Traverse City was weathered in with snow and winds of 70 mph. Lonnie Mixon was monitoring the situation at Detroit. He thought they could get to the Nordmeer going up the east side of the Michigan Peninsular. He proposed his plan to the Commanding Officer; a request was made to the District; District approved it. At 2:30 p.m., Lonnie departed. Co-pilot Jack Rittichier and Aviation Machinist David Nofftz rounded out the crew. They flew 150 miles through heavy snow, turbulence and gale force winds only 300 feet above the terrain with low ceilings and icing conditions. The final 80 miles they flew at 200 feet over Lake Huron, using the shoreline for navigation. The Nordmeer was located grounded on Thunder Bay Shoal in Lake Huron. Communications were established with the Nordmeer crew who advised they were stranded on the forward deck with no power or heat. Evacuation began and within 22 minutes, expert airmanship, accomplished the hoist of all eight crew members. to the icy heaving flight deck of the USCGC Mackinaw. Minutes after the operation was completed, the Nordmeer broke in half and all decks became awash.

An Air Force-Coast Guard Aviator exchange program was agreed to in 1967. The Coast Guard was to provide Three helicopter pilots and two fixed wing pilots, In July 1967. It was a volunteer program. LCDR Lonnie Mixon was one of the volunteers selected. The other two were LT Jack Rittichier, also from the Detroit Air Station and LT Lance Eagan. They were assigned to the 37th ARRS at DaNang for combat rescue duty. In preparing for this assignment, they attended the Air Force Survival School at Fairchild AFB, Washington. This was followed by training in the HH-3E twin engine amphibious helicopter at Sheppard AFB, Texas. They then received advanced combat crew training was commenced in January at Eglin AFB, Florida. This was followed by high altitude helicopter flying in the mountains near Francis Warren AFB, Wyoming and jungle survival training at Clark AFB in the Philippines. They arrived in DaNang on April 3, 1968. LCDR Lonnie Mixon would become the Squadron Scheduling Officer.

New rescue tactics had been developed. The HH-3E, a bigger more powerful, twin engine helicopter with armor and air-refueling capability was on scene. The HH-3E’s were painted a green camouflage and became know as a Jolly Green Giant. The Men who flew them in Southeast Asia came to be known as the Jolly Greens and the helicopter call sign became Jolly with a number.

The Jolly Greens became the best at what they did. Col. Frank Buzze who flew F-100s in the war wrote the following; “They were called Jolly Greens with near reverence by US combat pilots. Jet pilots are a pretty individualistic lot, and will argue about almost anything but a sure way to start something is for someone to bad-mouth the Jollys. No one did.” The Coast Guard aviators were fiercely proud to be part of the Jolly Greens. The Air Force treated them as their own. They were called “Coasties.” The term was one of respect.

On 6 June Lonnie Mixon with Captain William Byrd USAF as copilot, rescued a downed A-1 pilot from the top of a 5200 ft mountain 15 miles northwest of Khe Sanh. This operation is particularly noteworthy because the hovering performance of a helicopter falls off appreciably at high altitudes, especially when compounded by the hot humid weather that prevails in South Vietnam during June. With a C-130 tanker standing by, Mixon dumped fuel to reduce his weight to a minimum. From the charts, the power available vs power required to hover indicated “hover not possible.” Lonnie thought it could be done. He made his approach high enough so that he could come down the mountain to pick up translational lift if he was unable to maintain a hover. The helicopter came over the downed airman and the Jolly Green was able to maintain altitude while the forest penetrator was lowered and the survivor hoisted to safety. Mixon departed as soon as the penetrator was clear. He then refueled from the HC-130P tanker that had been orbiting above him and returned to DaNang. This is purported to be the highest rescue made by a HH-3E helicopter.

On 1 July Scotch 3, a F-105 Thunderchief was hit. Lt. Col. Jack Modica thought he could stay airborne long enough to reach the gulf. This did not prove to be the case and he was forced to eject just north of Dong Hoi. A second pilot in the vicinity saw the chute and noted the approximate position as Modica disappeared into the North Vietnamese jungle. It was a low -level ejection and when he hit the ground, he was knocked unconscious. It was two hours later that he filled the overhead FAC in on his condition. The time delay had given the North Vietnamese time to get to his location. To compound matters, he reported that something had happened to his back and he couldn’t move.

The first Jolly Green to go in was driven away several times and had to leave because of low fuel. LCDR. Lonnie Mixon USCG was next to try. The Sandys went in with suppression fire but Mixon soon learned it had little effect. The North Vietnamese hit him with ground fire and damaged a fuel tank, ruptured a hydraulic line, and knocked out part of the electrical system. He pulled off and the strike aircraft went back in. Darkness was falling but the rescuers decided to try one more time. Mixon told the On Scene Commander that his helicopter was still flyable and that he would go in and make the attempt. He started in and tracers lit the night as the helo was hit again and again. Mixon had to break it off. Modica, having hid himself the best he could, would spend the night on the ground. The next day a rescue was made by another Jolly with significant damage to the helicopter.

Not all rescue operations were downed airmen. The Jolly Greens were called upon by the Army to extract a special forces team, call sign, Carrot Top, which had come under heavy fire in the A Shau Valley in Laos. Jolly 10 and Jolly 28 were briefed by the on scene Spads (A1s out of Pleiku) that they had been conducting suppressive fire but due to a 1000-foot stratus deck directly above the LZ the results were questionable. Two Army UH-1F gunships were also on scene and when the ground party reported a pause in the ground fire Lonnie Mixon, in Jolly 28, with the gunships as escort made the first rescue attempt. The reconnaissance team was half way up the mountainside in a small clearing which ran up against a 2000-foot cliff face. Because of the rocky sides there was only one way in and out of the canyon. Mixon came to an abrupt hover 10 feet over the center of the shallow, elephant grass covered LZ. Near the rock wall ahead and to the left several men waited alongside the bright orange fabric on the ground that they carried for pinpointing their retrieval location. Mixon pivoted the aircraft, which measured three quarters the diameter of the circular clearing, to face his exit. As the turn was being completed a second group stood erect and began firing automatic weapons into the left side of the aircraft. The PJ in the back in back yelled, “Gunfire!” and the flight engineer simultaneously announced over the ICS that they had taken numerous hits and a fuel line had been severed causing a massive fuel leak. The copilot grabbed his rifle and shot back. Mixon finished the turn and flew the helicopter off the mountain. The PJ in back was unable to bring his weapon on target and didn’t fire. It is fortuitous that he did not. The two crewmen in the cabin were drenched with JP4 and the downwash from the rotor blades coming in through the open cockpit windows whipped up the volatile fuel, coating everybody and everything. For a time Mixon refrained from working any switch or using the radio for fear of a spark that would obliterate them. When they shut down the fuel boost pump for the severed line the leakage stopped. The flight back to DaNang took 45 minutes and upon landing they evacuated the aircraft immediately. Yet the days’ work for Mixon and his crew were not over. — They obtained a replacement HH3E, Jolly 21, and after briefing the 37th ARRS Commander and Operations Duty Officer on the situation, launched and returned to the rescue scene. Jolly 10, the second helicopter to make the rescue attempt was shot down. Two of the crew were killed. The two survivors joined with the Special Forces personnel and made their way to the bottom of the hill where a third Jolly Green made a successful rescue. Mixon and his crew flew High Bird on this pick-up.

Lonnie left Vietnam in April of 1969 at the end of his tour. During his tour he flew 395 Combat Hours, encountering armed resistance. Lieutenant Colonel Charles R. Klinkert, USAF, the 37th ARRS Commander in October 1968 said “The Coast Guard Aviators have been a terrific assist to the Air Force. Very few of us had any experience in this helicopter. These gentlemen came in here and helped us become real effective in this type of mission. I can’t say enough about them.”

The Commander of the 3rd Aerospace Recovery Group wrote a letter to the Commandant of the Coast Guard commending Lonnie for his dedication, willingness to accept responsibility and his ability to inspire others. He further commended Lonnie for his inputs to the ever changing concept of aircrew recovery; his extensive work with crews and pilots to insure proficiency; and His development of new water recovery tactics for both aircrew recovery and medical evacuations from small surface craft.

On March 7, 1969 he arrived at the Coast Guard Aviation Training Center (ATC) in Mobile Alabama. The Coast Guard had and was acquiring the H3 helicopter. Lonnie and the others that had flown the H3 in Vietnam were assigned as instructor pilots.

The Instructor conducted ground school as well as flight training. They also conducted “on site” transitions at the Air Stations that transitioned from the H-52’s. Annual proficiency training was provided. Annual proficiency training is now provided in simulators at the Training Center

CDR Lonnie L. Mixon retired on June 30,1973 after 22 years of service; Seven years enlisted and fifteen years commissioned. His duties varied and he accomplished them exceptionally well. During his career he was awarded:

Silver Star

Distinguished Flying Cross (2)

Air Medal (11)

Letters of Commendation (2)

Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Silver Star

Vietnam Service Medal

Vietnam Campaign Medal

National Defense Medal

Coast Guard Good Conduct Medal

Presidential Unit Citation

Coast Guard Unit Citation

U.S. Navy Combat Ribbon

USAF Small Arms Expert Ribbon

Vietnamese Unit Citation

Lonnie’s skill, courage, sound judgment and unwavering devotion to duty reflect the highest credit upon himself and the United States Coast Guard.

He most definitely made a difference

John Bear Moseley, CGAA Historian