Combat Rescue and Recovery

This is the story of those Coast Guard aviators who flew as part of the U.S. Air Force Combat Rescue Forces during the Vietnamese Conflict. The men who wrote this virtually unknown chapter of Coast Guard aviation history exemplified the highest traditions of Coast Guard Aviation and the United States Coast Guard.

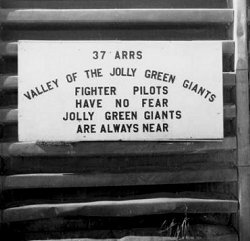

General Howell M. Estes, Jr., USAF, Commander, Military Airlift Command made the following statement about them. “I am personally aware of the distinguished record achieved by the pilots flying in combat with our Jolly Greens. They have flown many difficult and challenging missions and have consistently demonstrated their unreserved adherence to both our mottoes, — Always Ready and That Others May Live -They are indelibly inscribed in the permanent records of the stirring and moving drama of combat air crew recovery in Southeast Asia.”

The Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered that search and rescue forces be sent into Southeast Asia in May of 1964. The primary responsibility was given to the US Air Force.

When the first units of the Air Rescue Service arrived with the short range HH43B helicopters they were not prepared for the unique challenges of combat aircrew recovery in the jungles and mountains of Vietnam and Laos. (1) This was directly attributable to the draw-down of forces which took place in the late 1950’s. The concept, during this period, was one of massive nuclear retaliation and as a consequence the Air Force committed to a peacetime Search and Rescue capability. Helicopters were assigned to individual Air Force bases based on a study that determined that almost all accidents occurred within a 75-mile radius of the base of operations. Each base had a Local Base Rescue (LBR) detachment consisting of two and sometimes three helicopters. By the end of 1960, the Air Rescue Service (ARS) consisted of three squadrons and 1,450 personnel. (3)

During July of 1964 three HU-16 E’s from the 31st ARS and two from the 33rd ARS were assigned TDY to DaNang South Vietnam. They were used as mission control aircraft and for water rescues of downed airmen in the Gulf of Tonkin. By the end of 1964 Air Rescue forces had established four detachments, two in the Republic of Vietnam and two in Thailand. (4) Still manned and equipped for a peacetime operation, the Air Rescue Service was struggling to catch up. By June of 1965 the HC-54 assumed interim duties as the rescue control aircraft. They were later replaced by HC-130’s. In August 1965, A-1 Skyraiders began escorting rescue helicopters. In October the first of the HH-3E’s arrived. They had a good rescue hoist, drop tanks that increased the range, armament, and increased power provided by the T-58-5 engine. Of significant importance, was the titanium armor added to the HH-3s to protect the crew and key components of the helicopter. At the end of the year the Air Rescue Service inventory in Southeast Asia was; six HH-3E’s; one CH-3C; twenty-five HH43B/Fs; five HU-16E’s and two HC-54s. (5)

The first group of HH-3E’s, stationed at Udorn, was under the command of Major Baylor R. Haynes. John Guilmartin, who deployed with the group as a 1st Lt., stated that there were no written directives, no tactics, no rules of engagement, and no concept of combat rescue operations on the part of the Air Rescue Service. (6) Things improved but the rapid increase in rescue requirements generated by direct involvement of US forces created an acute shortage of experienced HU-16 and helicopter pilots. The Air Force approached the Coast Guard for supplemental help at the beginning of 1966. An aviator reciprocal exchange program was suggested. (7) It was not until March 1967 that the Coast Guard signed off on an implementing Memorandum of Agreement.

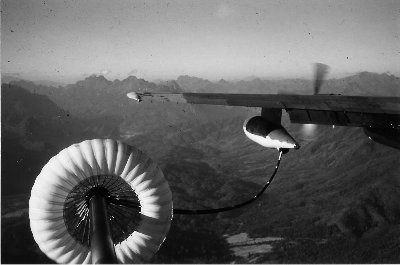

On 8 January 1966 the Air Rescue Service became the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service (ARRS), and the 3rd Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Group (ARRG) took charge of all rescue operations in the Vietnam geographical area. Improved tactics were instituted and better equipment came into being. In-flight refueling of the HH-3Es, utilizing HC-130Ps as refuelers, became operational in June of 1967. However, due to prior ambivalence toward the helicopter, the Air Force requirement for the HH-3E had not been scheduled into the production line and as a result, the desired number of aircraft was not obtained until the first quarter of 1968. The HU-16s, replaced by the HH-3Es, were phased out during the fall of 1967.

The HH-3E’s were called Jolly Green Giants, the name derived from the size of the helicopter and the green camouflage paint scheme. Not only did this naming system provide the rescue controller with information as to the type helicopter and the capabilities available to him but the name “Jolly Greens” would come to identify and reflect the proud heritage of these rescue forces. As tactics evolved, in good part due to the efforts of Major Haynes, the rescue task force (STARF) came into being. Basically, the STARF had a control aircraft, helicopters for recovery and fixed wing aircraft for protection and ground fire suppression. HC-130Ps (call sign Crown and later King) were used to coordinate the rescue effort and provide in-flight refueling. For most of the war it was the A-1 Skyraider that supported the helicopters.

This was a powerful reciprocating engine aircraft with massive firepower, durability, slow speed and loiter

capabilities that made it an excellent aircraft for interdiction and close air support. No amount of system analysis or staff studies will ever convince the men who were fighting the day-to-day war that the A-1 was not the right plane, in the right place, at the right time. The A-1’s based at Nakhon Phanom (NKP) had the call sign Sandy and those at Pleiku and DaNang used the call sign Spad. On a typical rescue, tactics called for four A-1s and two helicopters (Jolly Greens). The A-1s divided into two flights, Sandy Low and Sandy High. The helicopters and Sandy High went into orbit while Sandy Low assessed the situation. One of the Sandy Low pilots became on-scene commander with the job of locating the survivor, determining his condition, and assessing the landscape and enemy presence. When conditions seemed best he sent a helicopter in for pick up.

This helicopter, designated Low Bird, swooped in escorted by Sandy High. The other helicopter, High Bird, stayed ready to rescue the Low Bird crew if they ended up on the ground. Depending on the factors involved fighter escort (Fast Movers) for MiG combat air patrol was provided. (8) Few rescues in enemy controlled territory were accomplished without opposition. The enemy knew a rescue attempt would be made and developed tactics to ambush the rescuers.

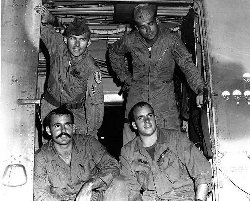

Orders were cut for the initial group of Coast Guard aviators under the Coast Guard – Air Force Aviator Exchange Program in July of 1967 (9) From the eighty plus volunteers two fixed wing and three helicopter aviators were selected.

The fixed wing aviators, both HU-16E qualified, were Lt. Thomas F. Frischmann and Lt. James Casey Quinn. Because the HU-16E was being phased out, both received TAD orders to attend the Advanced Flying Course (C130-B/E) at Sewart AFB and upon completion, to attend the Advanced Flying Course (HC-130P) at Eglin AFB. This completed, they received orders to report to the 31st ARRS, Clark AFB, Republic of the Philippines, arriving 3 June 1968. The mission was a series of rescue orbits over the South China Sea, escorts, medevacs, searches, intercepts and TDY deployments to other bases. Casey requested a transfer to the 39th ARRS, based at Tuy Hoa, in the fall of 1968. This was approved in early 1969. (10)

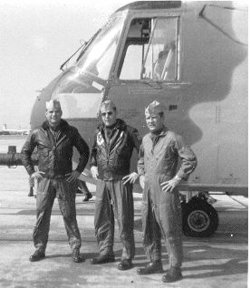

The helicopter pilots selected were Lcdr. Lonnie L. Mixon, Lt. Lance A. Eagan, and Lt. Jack C. Rittichier. They were assigned to the 37th ARRS at DaNang

for combat rescue duty. In preparing for this assignment they attended the Air Force Survival School at Fairchild AFB, Washington. This was followed by training in the HH-3E twin engine amphibious helicopter at Sheppard AFB, Texas. They then received advanced combat crew training was commenced in January at Eglin AFB, Florida. This was followed by high altitude helicopter flying in the mountains near Francis Warren AFB, Wyoming and jungle survival training at Clark AFB in the Philippines. They arrived in DaNang on April 3, 1968. (11)

Lt. Richard V. Butchka, Lt. James M. Loomis, and Ltjg. Robert T. Ritchie followed in April 1969. Lcdr. Joseph L. Crowe, and Lt. Roderick Martin III arrived in 1971 and Lt. Jack K. Stice, and Lt. Robert E. Long followed in 1972. All of these aviators were helicopter qualified and were assigned to the 37th ARRS at DaNang.

The 37th ARRS initially had 14 HH-3Es assigned. The squadron was authorized 21 each pilots and copilots but rarely would have more than 70 to 80 percent of that number on board. Only 25 percent of replacement pilots were qualified as Aircraft Commander. Experienced helicopter pilots had been a problem since shortly after initial deployment.

The situation was further impacted with the formation of the 20th Helicopter Squadron activated in October 1965 and the 21st Helicopter Squadron formed in 1967. These squadrons, part of the 14th Air Commando Wing, operated out of NKP and performed counter insurgency missions and mission support in the CIA war in Laos. This “Top Secret” operation, called Pony Express, further depleted the supply of experienced helicopter pilots available to the ARRS. ARRS requirements were met by transitioning fixed-wing pilots to helicopter operations. These pilots arrived in Southeast Asia directly from initial helicopter training. The Coast Guard aviators, well experienced helicopter pilots, arrived fully qualified. Though often junior in rank, the Coast Guard officers found themselves flying with a Major or Lieutenant Colonel as a copilot, but the rank disparity never interfered with the mission.

It did not take long for the Coast Guard aviators to become fully involved. Eleven days after arrival, Rittichier, in the face of hostile ground fire, participated in the rescue of the crew members of two U.S. Army helicopter gunships that had been shot down. The 1st Calvary Air Assault into the A Shau Valley had begun. * The downed Army aviators made contact with the on station C-130 overhead and gave their positions and the A-1’s and the Jolly Greens were called in.

Warrant Officer Chuck Germeck, US Army, one of the rescued aviators, relates the rest of the action as follows: “When the A-1s arrived we directed their fire at the VC positions and starting searching for an area where the Jolly Greens could get to us. The Jolly Greens came on station and we were directed to a small clearing just down from the top of the hill. As the first Jolly Green came in I heard heavy fire from the VC positions and he had to pull out. As I recall he made repeated attempts to hover over us, but at some point had to leave station. The A-1s came in for more runs against the VC positions. Then gunships from HHB and A Battery of the 2/20th ARA arrived. They hit the areas around us pretty hard as we directed them to VC positions using our emergency radios. Another flight of Jolly Greens arrived on station and they came in to pick us up as the gunships provided cover. My crew was the first to be pulled up the hoist. They took two of us at a time, my crew chief and gunner first, and then myself and W.O. Raymond. The second Jolly Green came in and pulled out Capt. Mill’s crew. As the Jolly Greens circled the area, I saw Air Force jets hit the hill with napalm. At DaNang we were treated to a fine steak dinner, with ice cream for desert. Not bad for us 1st Cav guys who were used to eating C rations for breakfast, lunch and dinner. After the customary handshakes and thank you’s, aircraft from 2/20th flew us back to LZ Sharon at Quang Tri. We arrived just in time to attend our own memorial service.”

* The A Shau Valley was one of the strategic focal points of the war in Vietnam. Located in western Thua Thien province, the narrow 25-mile long valley was

an arm of the Ho Chi Minh Trail funneling troops and supplies toward Hu� and Danang. At the north end of the valley was the major North Vietnamese Army (NVA) staging area known as Base Area 611. Because of its importance to the North Vietnamese plan for victory, the A Shau became a major battle ground from the earliest days of the American involvement in Vietnam.

The next week brought two more combat missions and on May 12 , Rittichier twice entered an extremely hostile area to rescue nine survivors of a downed helo, five of which were seriously wounded. The survivors were located in a very small landing zone, surrounded by tall trees, on the side of a steep mountain slope. Rittichier made the approach and departure by flare light. (12)

Mixon said the three of them wished to retain their Coast Guard identity but while doing so also wished to ensure that the Air Force knew they were fully committed to the squadron and the mission. They did both quite well. They purposely wore their khaki garrison caps with their rank displayed on one side and the Coast Guard Eagle on the other. They lived and breathed helicopters and were well received, sometimes with bemusement, by their Air Force counterparts. These men, and the ones who came after them, possessed a deep seated belief that no one was better prepared and qualified to fly rescue helicopters than Coast Guard aviators.

On 6 June Lonnie Mixon with Captain William Byrd USAF as copilot, rescued a downed A-1 pilot from the top of a 5200 ft mountain 15 miles northwest of Khe Sanh. This operation is particularly noteworthy because the hovering performance of a helicopter falls off appreciably at high altitudes, especially when compounded by the hot humid weather that prevails in South Vietnam during June. With a C-130 tanker standing by, Mixon dumped fuel to reduce his weight to a minimum. From the charts, the power available vs power required to hover indicated “hover not possible.” Lonnie thought it could be done. He made his approach high enough so that he could come down the mountain to pick up translational lift if he was unable to maintain a hover. The helicopter came over the downed airman and the Jolly Green was able to maintain altitude while the forest penetrator was lowered and the survivor hoisted to safety. Mixon departed as soon as the penetrator was clear. He then refueled from the HC-130P tanker that had been orbiting above him and returned to DaNang. This is purported to be the highest rescue made by a HH-3E helicopter. (13)

Three days later tragedy struck. Hellbourne 215, a Marine A-4 had gone down northwest of the A Shau Valley. The downed aviator was located with his parachute a few yards from a road that ran east-west with a steep hill overlooking his position. Trail 36, the forward air controller (FAC), who had been in contact with Hellbourne 215, reported that the downed airman had a broken leg and a possible broken arm and would probably would require a PJ to assist him. Numerous suppression strikes by Spads and A-4 aircraft had been directed into the area to keep the strong enemy forces away from him. The first HH-3E to attempt the pick up, Jolly 22, Maj. Art Anderson, made three approaches. Intense fire suppression activity followed every approach. Each time extremely heavy enemy ground fire drove the helicopter away. After the third approach, Jolly 22 had to depart because of critical low fuel, leaving Lt. Jack Rittichier USCG, who was High Bird, as the only rescue helicopter on scene. Trail 36 asked Rittichier if he would be able to make the rescue attempt. He answered affirmative and requested the Scarface gunships and A-1s to suppress ground fire as he went in. Enemy fire became so intense that he could not maintain his hover and he had to pull away. The Spads, (A-1 Sky Raiders) poured on more suppression fire. Rittichier, after determining his aircraft was OK, came around for a second try. He was led in by Trail 33 along with 2 gunships and 2 Spads for cover. Throughout the approach he relayed the direction of incoming fire until coming to a hover over the downed pilot.

Bob Dubois, pilot of Trail 33 wrote the following; “Jolly Green 23 went into a hover over the A-4 pilot and turned to the west. The PJ was on the wire being lowered when Jolley Green 23 reported he was taking heavy fire. I saw fire coming out of the left side near the engine and I told him he was on fire and to get out of there. He started to pull out and I advised him that there was a clearing 1000 meters north if he had to set down. He said he was going for the clearing. He was in descent but still above the height of the trees along the edge of the clearing when the main rotor stopped turning. Jolly Green 23 hit the ground and burst into flames that consumed anything that looked like an aircraft.” Lt. Jack Rittichier and the rest of his crew were lost with the aircraft. (14)

In 1991, Lt. Rittichier was enshrined in the USCG Aviation Hall of Fame, Erickson Hall, at Aviation Training Cemter, Mobile, Alabama. Lt Rittichier and his crew remained missing in action for 35 years until the remains were identified and recovered in 2003. He was buried on Coast Guard Hill in Arlington National Cemetery on October 6, 2003.

In Vietnam, the rescue pilot was faced by two major obstacles in the recovery of downed pilots. First the triple canopy on jungle trees rising 200 feet above the tangled bush, karst*, mountainous terrain, and swamps. The forest penetrator, a plumbbob-like device that carried the hoist cable through the thick foliage, was developed to cope with this problem. It could be ridden down and used to extract the downed airman. The second was enemy opposition. With Soviet help the North Vietnamese constructed one of the best integrated air defense systems in the world. This included MiG interceptors, SA-2 missiles and a stable of antiaircraft guns from 23mm to radar directed 100mm weapons. The North Vietnamese shrewdly did not challenge the US air superiority; instead they concentrated on achieving “air deniability,” that is, denying the use of the air in specific locations. Throughout the war 23mm, 37mm, and 57mm weapons, working in combinations with heavy machine guns were placed in areas with large numbers of combatants. These weapons were mobile and could be moved from location to location. A rescue helicopter flew at a slow speed and a low altitude so these weapons posed a great threat. Red dots on charts carried by the helicopters showed where these guns were known to be. Some areas on these charts were solid red. If a pilot could fly his crippled aircraft to an isolated jungle area, or if he could head out over the Gulf of Tonkin, his chance of rescue increased. Isolated jungle areas, designated as a SAFE areas (Selected Area for Evasion) were much better than those infested with enemy troops, like the Ho Chi Minh Trail. (15)

* A limestone region marked by sinks, abrupt ridges, irregular protuberant rocks, and underground streams.

On 1 July Scotch 3, a F-105 Thunderchief was hit. Lt. Col. Jack Modica thought he could stay airborne long enough to reach the gulf. This did not prove to be the case and he was forced to eject just north of Dong Hoi. A second pilot in the vicinity saw the chute and noted the approximate position as Modica disappeared into the North Vietnamese jungle. It was a low level ejection and when he hit the ground he was knocked unconscious. It was two hours later that he filled the overhead FAC in on his condition. The time delay had given the North Vietnamese time to get to his location. To compound matters, he reported that something had happened to his back and he couldn’t move.

The first Jolly Green to go in was driven away several times and had to leave because of low fuel. Lcdr. Lonnie Mixon USCG was next to try. The Sandys went in with suppression fire but Mixon soon learned it had little effect. The North Vietnamese hit him with ground fire and damaged a fuel tank, ruptured a hydraulic line, and knocked out part of the electrical system. He pulled off and the strike aircraft went back in. Darkness was falling but the rescuers decided to try one more time. Mixon told the on scene commander that his helicopter was still flyable and that he would go in and make the attempt. He started in and tracers lit the night as the helo was hit again and again. Mixon had to break it off. Modica, having hid himself the best he could, would spend the night on the ground. (16)

The next morning the Jollys tried again but it didn’t go well. An A-1 was shot down, killing the pilot and a badly shot up HH-3E was returning to DaNang with a rocket lodged in the belly. It had penetrated a fuel cell but had failed to explode. Rescue forces were recalled. Several hours later, after a B-52 bomber strike close to the scene, a decision was made to make another attempt.

Jolly 21 was low bird and the crew, Lt. Lance Eagan, USCG, Aircraft Commander, with Maj. Bob Booth, USAF copilot, Sgt. Herb Honer, Engineer, and A1C Joel Talley PJ, knew that it was going to be a rough one. They would have to penetrate a well established “flak-trap” in order to make the pick up. Lance descended through very heavy 37mm anti-aircraft fire using twisting evasive maneuvers. He took several hits and the concussion from airbursts staggered the helicopter. Then he was through it and into the a box canyon peering for Scotch 3 through the triple canopy. Eagan made radio contact and could see the smoke the downed airman was sending up, but due to the extremely dense jungle, it was impossible to sight the man. Modica was unable to help himself which made it necessary to send the PJ down on the penetrator. Eagan spotted a small opening in the jungle near Modica’s smoke, and Talley was lowered. Once on the ground Talley looked up at the flight engineer who pointed in the direction of Modica. The undergrowth was so dense it took him a good bit of time to find the man. It was determined Modica’s pelvis was broken and that he must be moved as little as possible.

Talley used his radio to vector the helicopter to his position. Eagan found himself in a small valley with tall trees and three sides rising 200 ft above him. There was no hostile fire directed at the Jolly 21 at this point in time but Eagan knew the North Vietnamese would zero in on the smoke. He had to get to Talley and Modica quickly and bring them up. With his height above the terrain limited by the length of the hoist cable, he edged ever closer to Talley’s position. The rotor blades lopped off tops of the trees as he went, until he could get no closer to a towering dominant tree that the injured pilot lay against. The penetrator was dropped and Talley carried the pilot the short distance to it. He had been on the ground for 18 minutes. He strapped himself and the pilot in then pushed his radio switch. Eagan heard Talley say “Take us up”. The flight engineer started the hoist up and at that instant Eagan caught sight of movement in front of him. The whole world seemed to erupt. The enemy, waiting for the moment of vulnerability, sprang the trap. Intense automatic weapon fire came from below and in front of the helicopter. Hostile fire punctured the windshield spraying powdered glass all over him, but Eagan could not move until the PJ and rescued pilot cleared the tree tops. It seemed like an eternity then he heard a shout from the back that Modica and Talley were clear of the trees. Without hesitation he pulled away, with the PJ and injured pilot swaying below the aircraft. He turned the aircraft to shield them from the ground fire. Once everyone was on board, he went direct to the field hospital at Dong Ha.

Eagan and his crew checked their Jolly. The titanium armor plating and luck saved them. The intensity of the fire showed in their battle damage. They had taken direct hits from large caliber automatic weapons. A total of 40 bullet holes were counted in the fuselage; the tail section had a gaping hole; four of the five rotor blades had been hit; and the self sealing fuel tank had nine punctures in it.

Eagan had missed being killed by a matter of inches and the copilot was saved by the titanium plating under his seat. The Jolly green was deemed unflyable and was transported back to DaNang by a CH 54B Skycrane helicopter. The rescued pilot, Lt. Col. Jack Modica, was quoted as saying, “I’ve heard of the incredible jobs done by the rescue forces and now I’m convinced of it!” (17)

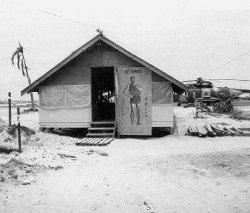

The daily mission commitment had two HC-130Ps out of Tuy Hoa providing continuous coverage of two holding points; one over the Gulf of Tonkin and the other over Laos. The 37th AARS would place one or two HH-3E’s orbiting over the Gulf of Tonkin; two HH-3Es on strip alert at DaNang; and two likewise deployed to Quang Tri which was nearer the North Vietnamese border. The holding patterns and the strip alert at Quang Tri cut down on the response time. If you could get to a downed airman within 35 minutes the rescue probability was good but after that it fell off rapidly. Quang Tri was a U.S. Marine compound where the pilots had their own shelter referred to as the “alert shack.” It had a floor, cots, several chairs, a VHF-FM radio. Next to it was the outhouse.

Not all rescue operations were downed airmen. The Jolly Greens were called upon by the Army to extract a special forces team, call sign Carrot Top, which had come under heavy fire in the A Shau Valley in Laos. Jolly 10 and Jolly 28 were briefed by the on scene Spads (A1s out of Pleiku) that they had been conducting suppressive fire but due to a 1000 foot stratus deck directly above the LZ the results were questionable. Two Army UH-1F gunships were also on scene and when the ground party reported a pause in the ground fire, Lcdr. Lonnie Mixon, USCG, in Jolly 28, with the gunships as escort made the first rescue attempt. The reconnaissance team was half way up the mountainside in a small clearing which ran up against a 2000 foot cliff face. Because of the rocky sides there was only one way in and out of the canyon. Mixon came to an abrupt hover 10 feet over the center of the shallow, elephant grass covered LZ. Near the rock wall ahead and to the left several men waited alongside the bright orange fabric on the ground that they carried for pinpointing their retrieval location. Mixon pivoted the aircraft, which measured three quarters the diameter of the circular clearing, to face his exit. As the turn was being completed a second group stood erect and began firing automatic weapons into the left side of the aircraft. The PJ in the back in back yelled, “Gunfire!” and the flight engineer simultaneously announced over the ICS that they had taken numerous hits and a fuel line had been severed causing a massive fuel leak. The copilot grabbed his rifle and shot back. Mixon finished the turn and threw the helicopter off the mountain. The PJ in back was unable to bring his weapon on target and didn’t fire. It is fortuitous that he did not. The two crewmen in the cabin were drenched with JP4 and the downwash from the rotor blades coming in through the open cockpit windows whipped up the volatile fuel, coating everybody and everything. For a time Mixon refrained from working any switch or using the radio for fear of a spark that would obliterate them. When they shut down the fuel boost pump for the severed line the leakage stopped. The flight back to Da Nang took 45 minutes and upon landing they evacuated the aircraft immediately. Yet the days work for Mixon and his crew were not over. — They obtained a replacement HH3E, Jolly 21, and after briefing the 37th ARRS Commander and Operations Duty Officer on the situation, launched and returned to the rescue scene. Jolly 10, the second helicopter to make the rescue attempt was shot down. Two of the crew were killed. The two survivors joined with the Special Forces personnel and made their way to the bottom of the hill where a third Jolly Green made a successful rescue. Mixon and his crew flew High Bird on this pick-up. (18)

In the Air Force qualification system, a pilot started as a co-pilot and by means of training and experience became a qualified Aircraft Commander. The next step up was the designation of Instructor Pilot, a pilot qualified to train others. Top qualification was Flight Examiner. The Coast Guard aviators arrived as fully qualified Aircraft Commanders and all had a good amount of helicopter flight time — most of it in the HH-52 with much the same characteristics as the HH-3E. As a result they were designated Instructor Pilots and were used extensively to train newly arriving pilots. Butchka was designated a Flight Examiner. Lieutenant Colonel Charles R. Klinkert, USAF, the 37th ARRS Commander in October 1968 said “The Coast Guard Aviators have been a terrific assist to the Air Force. Very few of us had any experience in this helicopter. These gentlemen came in here and helped us become real effective in this type of mission. I can’t say enough about them.” (19)

MSgt. Jack Watkins put it another way. “The crews liked to fly with the Coast Guard pilots. It went beyond personalities. The Coasties were all experienced and excellent helicopter pilots and when on a mission they were able to readily adapt to any situation. Flying the helicopter was natural to them. Their “saves” were duly recorded. What really can not be determined is — how many of us made it through our tour due to the willingness of Mr. Mixon and Mr. Eagan to pass along their skills to the other pilots.”

The praise was not just at the local level. The Commander 3rd ARR Group wrote a letter to the Coast Guard Commandant praising the Coast Guard aviators for their courage and flight ability and additionally noted the extensive work they had performed in developing highly proficient crews. Mixon was further cited for developing new improved water recovery tactics and medical evacuations from surface vessels. Col. Klinkerts statement on effectiveness was correct. The Jolly Greens became the best at what they did. A number started with little experience but of necessity they learned fast and they learned well. No one can question the their courage and dedication to the mission. A number of the pilots flew on second and third combat tours and the enlisted crews were almost all multi-tour vets by 1972. Col. Frank Buzze who flew F-100s in the war wrote the following; “They were called Jolly Greens with near reverence by US combat pilots. Jet pilots are a pretty individualistic lot, and will argue about almost anything but a sure way to start something is for someone to bad-mouth the Jollys. No one did.” The Coast Guard aviators were fiercely proud to be part of the Jolly Greens. The Air Force treated them as their own. They were called “Coasties.” The term was one of respect.

The Coasties had a little fun with being unique within a unique organization. They made up special squadron patches with the Coast Guard stripe and insignia on it. Butchka, Loomis, and Ritchie carried on the tradition when they sent Christmas Cards out from the “Coast Guard Air Station DaNang.” In fact the Air Force people joined in the little tongue in cheek exercise. When Jack Stice and Bobby Long arrived at DaNang in ’72 they were greeted by the following in the squadron newsletter. Under the heading; – “Coast Guard Air Station Da-Nang” — they were welcomed aboard. The article said in part; “They say they are not 2ndLts. or 1stLts. but full lieutenants (whatever that means). How did they do it? Well Jack and Bobby didn’t have any MAC regulations to prevent it. They didn’t even fill out a DOD or an AF form. Luckily the 3rd Group inspection team did not get hold of them. Due to the lack of records, forms, and regulations we can only assume they are qualified.”

The second group arrived in April of 1969. Their arrival and the fact that they were all qualified Aircraft Commanders was happily noted in the units

Historical Record. Shortly after arrival Lt. James Loomis, USCG, flew two back-to-back Coast Guard type missions. On two separate occasions in less than three days, Loomis and his crew evacuated personnel who had been injured at sea. Each of the missions covered almost one thousand miles, over water. Using in-flight refueling, each mission was accomplished non-stop taking eight hours. The flights were made at night. At the time they were the longest over water medivacs that had ever been made by helicopter. Comments made by Lt. Butchka, Lcdr. Crowe and Lt. Stice, confirmed by entries in the 37th ARRS SAR Log, indicate that operations involving naval surface vessels was a “Coastie” operation. This would continue through to the cessation of hostilities.

Casey Quinn had transferred to Tuy Hoa and was flying the C-130P directing recovery missions and refueling Jolly Greens. Lt. Dick Butchka, Lt. James Loomis, and Ltjg. Rob Ritchie were at DaNang flying with the 37th ARRS. In order to identify each other Jim Loomis came up with a system. Casey was Coast Guard 1, Butchka was Coast Guard 2, Loomis 3, and Ritchie 4. Casey said. “This was well received at the squadron level but a few of the Colonels were not terribly impressed with our humor and thought we were nuts — but I convinced my crowd that I had them surrounded.”

a HC-130P tanker.

Casey Quinn was on a Laos orbit and Rob Ritchie was over Laos looking for Nail-53, a downed OV-10 pilot. The thick jungle canopy was making it difficult to locate the survivor but Ritchie knew him to be somewhere on the west slope of the valley. Radio contact was established. Nail 53 could hear the helicopter but he could not see it. After further conversation Ritchie felt he had the pilot fairly well located and he lowered the penetrator. At this point radio contact was lost. Ritchie left the penetrator down as it was routine procedure for a survivor on the penetrator to signal he was ready to be pulled up by shaking the cable. After a reasonable period of time the penetrator was raised and Ritchie moved to another spot, sending it down again. This continued but Nail53 did not respond. The low fuel warning lights came on and Ritchie informed Casey that he would need fuel. After a few more minutes without a nibble he told his flight engineer to take up the penetrator because they had to get out of there. The flight engineer responded that it felt like someone was near the penetrator. Shortly thereafter came the pull up signal. When the low fuel lights came on in an HH-3 the pilot had 15 to 20 minutes of fuel left. Five minutes had gone by since the initial warning. It took additional time to reel in 210 feet of cable and get the survivor inside. Rob Ritchie alerted Casey that his situation was critical – if he could not hit the drogue on the first try he would be in need of rescue.

Under a full power surge Ritchie commenced his climb. Suddenly the adrenaline flowed as something dark and massive appeared below him. It was an HC-130P with drogues streaming. Casey had left orbit and amazingly came up under the Jolly Green before he cleared the ridge line of the compact valley. Ritchie plugged in and they climbed out as one. (20)

Note: Hitting the refueling basket in a drogue streaming from the HC-130 requires a measure of skill. The target tends five degrees left of the helicopters center line and to get the probe into the basket the pilot enters into air turbulence caused by the C-130s engines. The long probe extending forward will dip when the helicopter accelerates and rise when it decelerates . The pilot starts above the basket and flies into it. Furthermore, the probe has to impact the drogue with at least 160 foot-pounds of force for a seal to occur. Quinn came under the HH-3E as it was climbing out to put Rob in the right position. Ritchie hit the probe on the first try. The coordination, dexterity and the marked degree of flying skill on the part of both pilots was exceptional.

Casey got another chance to once again test his skill a short time later. Word came in that two crewmen had just ejected from SeaBird 02 (F-105) just north of the Mu Gia pass in North Vietnam. Casey was aircraft commander of a HC-130 launched as King 3 to supplement King 2. The mission of the C-130s was dual purpose. They provided in-flight refueling for the helicopters and mission control of the rescue effort. They were the command aircraft and coordinated with all the forces used in the recovery. The communication equipment was extensive providing UHF, VHF, HF, and FM capabilities. Casey stated that the coordination within the C-130 was essential and the professionalism of the crews was outstanding.

Casey rendezvoused with two HH-3E’s, four HH-53s and four A-1s. King 2 recommended a holding pattern, five miles west of the Laotian border for Casey’s incoming flight and their fighter cap of Fast Movers. (a term applied to F-105s, or F-4s). The Joint Rescue Control Center did not concur with the recommended location because of SAM activity and directed him to a point nineteen miles further south. Casey did not know it at the time, but the JRCC did not notify the fighter cap of the change in plan. Refueling began on a westerly heading with the north-south ridge line reaching to 7500 ft below them. Casey was in communication with the Jolly Greens. The co-pilot, 1st Lt. Joe Ryan and the Navigator, Maj. Tony Otea, were monitoring the operational frequencies for MiG and Sam activities. Tony plotted the locations on the navigation chart. The HH-3’s fueled first, hooking up at 8000 feet, the highest the H-3 could fly, keep up with the C-130 and not stall out. Casey had 70% flaps down and was flying at just over 100kts. The two H-3 helicopters had fueled and Jolly 70, a HH53B, was moving into position. Jolly 71 and Jolly 72 were in a loose trail with a Sandy sitting outboard. Jim “Jinks” Bender, who was in Sandy 04 said; ” A report came in on a MiG in our vicinity. This is when the first MiG hit the formation. The first missile missed and the second hit Jolly 71 and it disintegrated. Everyone started yelling — Migs – Migs — TAKE IT DOWN! — We headed for the weeds.” The Helicopters made for the ground at max rate and Casey sent his C-130 diving toward earth. The refueling baskets for the helicopters were larger than those used to fuel the jets and had a max speed restriction when extended. This speed was exceeded before the drogues were fully retracted and both were lost on the way down.

A second MiG-21 joined in and came after Casey’s C-130. Casey by now was at tree top level. Jolly 72 called out that a MiG passed his right side and was

headed for Casey. When Casey was back at Eglin AFB checking out in the HC-130P he had stated that the “Herk” performed so well that it was like a four engine fighter plane. He was going to get the chance to prove it! Casey said he knew it would take three to five seconds for the MiG to get a missile lock, so he picked the canyon just ahead and jinked and flew his “Herk” in a series of unpredictable erratic maneuvers between the walls at tree top level. No missiles were launched that Casey knew of but he could see the bursts from the MiG’s cannon hit the karst ahead. He said he was too busy to dwell on it. Moments later the C-130 emerged from the canyon — the MiG-21 never did! Casey got his MiG, but due to the chaos that existed, never got confirmation on the “kill.” (21)

LT. COL Tyner, Squadron Commanding Officer Presenting a medal to LT Casey Quinn(USCG) along with CAPT Mitchell (USAF).

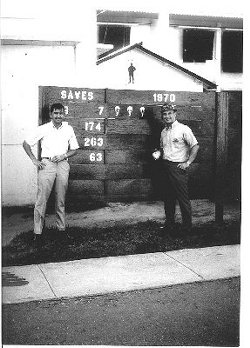

The goal of the combat rescue and recovery units was to get to those in peril before “Charlie” did. Whether the mission was an extraction or the pick up of a downed airman, each time they were successful it was a win! It was called a “save” but a ” save” was much more than a statistic to these men. A “save” was a person and they took it personally. The 37th ARRS was coming up on the 500th “save” in mid October 1969 and everyone was looking forward to it. They got number 497 and then hit a dry spell for about a week. On 24 October Misty 11 went down. Lt. Dick Butchka USCG got numbers 498, 499, and 500. Ltjg. Rob Ritchie USCG got number 501 and 502.

Northeast of Saravane, Laos, Misty-11, an Air Force F-100F flying ground interdiction had engine failure due to antiaircraft fire. The two crewmen were forced to eject. An airborne FAC, Nail 07, reported both survivors touched down within a hundred yards of one another and that he was in radio contact with them. Misty 11A had a broken leg, 11B was unhurt. Before sending in the helicopter the A-1s trolled the area but their repeated passes brought no response. Lt. Dick Butchka, in the high bird slot orbiting at 3000 feet, watched his good friend, Captain Charles Langham USAF, descend for the recovery. Langham came to a hover over Misty 11A and lowered his PJ by hoist. The PJ immediately had the downed airman on the forest penetrator and gave the cable-up signal. Less than a minute had elapsed. When the penetrator was approximately10 feet off the ground the helicopter came under fire. Butchka saw three sides of the blind canyon twinkling. The Skyraiders rushed in to suppress the fire, but the opening volley had shot the hoist assembly off its mounting, sending it crashing into the flight engineers chest. Realizing the hoist was inoperative the flight engineer hit the switch cutting the cable and yelled to Langham to pull off.

Up above, Butchka had punched off his aux tanks and went into a plunging descent at max rate. Seeing Langham’s aircraft smoking and throwing fluid, Butchka told him to put it on the ground. Langham searched for a clear spot and put the aircraft into a small punch bowl shaped valley. Langham and crew jumped out of the helicopter into the elephant grass, looking up for high bird. They did not have far to look. Butchka’s helicopter was in a 25 foot hover on the left side of Langham’s with its cable waiting. Butchka expected ground fire at any minute. During the swift pick up the helicopter took a jolt in the right side that holed the skin with a gash eight inches long by two inches wide.

With the men safely on board the next problem was getting out of there. Butchka did not want to go back out the way he came in because of heavy enemy fire. It was hot and humid, the pressure altitude was high, and the only other way out presented him with a vertical face of about 130 feet. It was decision time. Butchka said; “I headed for the face, – pulled every bit of power I could, and with a little bit of airspeed, — drooped the rotor to 94%, — and just cleared the top.” As he cleared the ridge line the Jolly immediately came under heavy ground fire from a different direction. Sandy lead hadn’t reported anything because he didn’t know where Butchka was. Miraculously they were not hit.

There were still two Misty crewmembers and Langhams PJ on the ground. The PJ, TSGT D.G. Smith, directed air strikes that bracketed his position. Jolly 76, out of Udorn made three recovery attempts, but each time he received intense ground fire, resulting in extensive battle damage. Jolly 76 had to withdraw.

Later that afternoon the Jollys tried again. The Sandys made suppression runs and laid smoke. Ltjg. Rob Ritchie made his run. The normal procedure was to come into the wind.

Ritchie used the smoke for cover, approached from a different direction, and came in down wind. He swooped in fast and quickly put the aircraft into a hover over Sergeant Smith. After getting Smith and the injured crewmember on board, Rob moved to recover Misty B but was driven off. He would make three more attempts but the element of surprise was now lost. On the third try his hoist was shot away and he had to break off any further attempts. Misty 11B was recovered late that day by yet another helicopter. (22)

Coast Guard aviators Lcdr. Jay Crowe and Lt. Rod Martin arrived at the 37th ARRS in May of 1971. The HH-53 Super Jolly had replaced the HH-3E. The HH-53 was larger, more heavily armed, and with almost double the shaft horsepower, it had better overall performance and hover capability, especially at altitude. The air campaign was active in southern North Vietnam and the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos. On 4 June two Covey (OV-10) FAC crewmen successfully ejected over a heavily defended area, near Boloven’s Plateau in Laos, after the aircraft had been hit by enemy ground fire. The area, which contained a considerable number of anti-aircraft weapons, was first hit by Fast Movers and then hit again by the Sandys. Sandy lead felt there was one part of the area that was too close to the downed pilots to “sanitize” so they planned to obscure this with smoke just prior to the Jollys run inbound.

Lcdr. Jay Crowe, USCG, in Jolly 64 planned to fly at maximum speed at tree top level along the canyon rim. * He left orbit, dropping at several-thousand-feet-per-minute, with the escort Sandys joined up and rolled out at 170 knots on the inbound heading. He noted how “watching the Sandys lay smoke, swirl around in rocket, machine gun, and CBU passes really got the adrenaline flowing. By the time you can discern whose tracers are whose, you’re too busy to do anything except to trust in God and the Sandys and jink like hell.” The first survivor was located and hoisted without difficulty. The second was different. He was on a jungle-covered ridge within the canyon. Trees were taller than the 250-foot rescue cable, so Crowe carefully eased the helicopter down into the tree canopy, mowing a vertical path with the main rotor blades thus enabling the penatrator to reach downed airman. During egress the helicopter came under fire which was returned by the PJs but damage sustained was light. (23)

This one went well! Crowe said “I can not describe the sensation of victory I had as we rode wing on King (HC-130P, on-scene control aircraft and tanker), taking on fuel with the fast movers making aileron roll passes and loops around us; the sky was never quite so blue or the clouds so puffy white.”

Major Ross, the second pilot to come out, said that he made radio contact as soon as he took cover. He added, “When I heard the Jolly Greens were coming, I was so damned happy I couldn’t believe it! I knew if anybody could get us out, they would do it. I knew what kind of people they were and there’s just something about the words Jolly Green – it stays with you from the first time you hear it until the time you need their skills.” In one of those “can you believe this?” situations – Jay would again pick the same two pilots up several weeks later.

* With the improved performance of the rescue helicopters, such as the HH-53, terrain became a useful ally rather than a hindrance. The ridge lines, karst, and jungle canopy could now be used to minimize the effectiveness of enemy fire. The antiaircraft guns, which grew in number and caliber throughout the war, were limited by the same jungle that hid them. Gunners could track their targets only within the confining limits of geographic features.

Summer came and the action continued. Martin brought his total to eight saves and Crowe got a couple more in an unusual way. He scrambled out of Bien Hoa to pick up two downed airmen in Cambodia. The two survivors were in an area surrounded by enemy forces. Crowe got a thorough briefing enroute to the pickup area by the on scene FAC. The location of the downed airmen was well marked, so rather than sanitize the area Crowe initiated a rapid descent from 8000 feet using a spiraling autorotation to a power recovery. Surprise was complete. The survivors were taken on board followed by immediate departure. Sporadic tracer fire was noted on departure but no damage was sustained by the aircraft. (24)

The organization of the ARR Squadrons differed from the norm. The Air Force is organized into Wings composed of Groups which are in turn made up of Squadrons with separate flight and maintenance commands. The ARR Squadrons were under the operational control of the 3rd ARR group at Tan San Nhut but were unique in that they were self sufficient within the squadron and combined the maintenance and flight operations under one command. The commanding officer was a Lt. Colonel and a pilot. Under his command was an Operations Officer, A Maintenance Officer, and an Administrative Officer. Responsibilities are reflected by the title. The Administrative Officer was normally a non-pilot; The Maintenance officer could be either a pilot or a non-flying officer. The Operations Officer, always a pilot, was a Major and was second in command. Each section had a staff of enlisted specialists. Collateral duties for squadron pilots were operational only. Jay Crowe, Lonnie Mixon, and Jack Stice served as squadron Operations Officers. It is in this capacity that Jay Crowe planned the Quang Tri evacuation. This was later referred to as the Miracle Mission.

Grouped in the Citadel, a walled military compound in the middle of Quang Tri proper, were 132 people, American advisors, and members of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). Caught in the onslaught of the North Vietnamese offensive that had begun March 30 1972 with a drive across the DMZ, Quang Tri was now surrounded by four North Vietnam Army (NVA) divisions. The enemy had cut Highway 1, the only escape route south to safety, and had been pounding Quang Tri with artillery, mortars, and rockets for several weeks. There was only one way out — by helicopter. On May 1, five HH-53s of the 37th ARRS were prepared to do just that.

The potential for disaster was as great as the potential for success. The mission had to be well planned and executed. Planning was the responsibility of Lcdr. Crowe, the squadrons Operations Officer. He used elements from the US Air Force, US Army, and the US Navy.

If the helicopters went in low, they would be subject to intense ground fire, including the hand-held Quail – a heat-seeking missile. If they went in high, then the SAMs became the problem. There simply was no ‘safe’ altitude. What made the situation even more difficult for the Jolly Greens was the fact that the landing zone was small. Located inside the Citadel, it was large enough for only one helicopter at a time. And like everything else of military significance in Quang Tri, the LZ had been zeroed in by enemy artillery for several days. Add to that the fact that any approach to the Citadel was over several miles of NVA held territory. Losses greater than 25 percent were expected.

According to the evacuation plan, three helicopters, with two on airborne standby, would be needed to get the people out. Number one on the list of priorities was to suppress and eliminate the AA batteries and heavy equipment in and around Quang Tri to the maximum extent possible. Bilk 11 (O2 Cessna Skymaster) was the FAC and directed the Fast Movers (F4 Phantoms) on a series of strikes to accomplish this. The Sandys (A1- Skyraiders) were next and suppressed a corridor from the citadel to the beach east of Quang Tri. Orbiting over the coastline, the Jolly crews were kept abreast of everything happening on the ground and in the air. Aboard the first helicopter was an Army aviator who had been into the Citadel many times. He would serve as a guide to the LZ for the lead Jolly Green. Sandy lead came up on the radio and directed the first Jolly Green to a point on the beach where he had put smoke. This would be the entry point for the run to the citadel.

The Sandys did their job well, strafing and bombing enemy positions. They accompanied the Jollys in but there were so many enemy troops below that the Jolly Greens would still had to weave through a corridor of ground fire from tanks and antiaircraft guns. Then, on the ground even for a few minutes, they were extremely vulnerable. Despite constant radio chatter no one in the helicopter paid any attention — all eyes were on the LZ, now only a few meters away, and the crowd of people waiting for the first Jolly Green. Artillery and rocket shells were exploding all over Quang Tri, and a heavy smoke screen had been laid and blanketed three sides of the LZ. When the number one Jolly Green touched down, 37 people were loaded and it departed immediately. Number two Jolly Green followed and picked up 45 people. The rest came out on Jolly Green number three.

By 1850 hours, the operation was over. Everybody was safe at Da Nang. But the most incredible part of the story was just being realized. Not one crewmember or evacuee sustained any injury whatsoever! Moreover, there was not one bit of battle damage to any helicopter! Not even a single bullet hole! One Sandy supporting the rescue was downed, as was a FAC aircraft, both pilots were saved. The FAC pilot bailed out and was rescued by friendly ground forces. The Sandy pilot ditched his A-1 in the ocean and was picked up by an Army helicopter. Lt. Colonel Harris, the 37thARRS Commander, was effusive in his praise of the team effort represented by the Quang Tri rescue. He said, “Without the support of the FACS, the F-4s, the Sandys and the Navy, we couldn’t have pulled this one off at all. I also hope everyone will remember the team members who didn’t make the headlines.”

In the process of planning and coordinating this mission Jay had become privy to considerable amounts of classified information. As a result he was not allowed to participate in the rescue operation or fly any further missions during the last month of his tour. (25)

At the beginning of 1972 the South Vietnamese Army deployed a new division, the 3rd, along the DMZ in the fire bases formerly occupied by American Marines. A dry season communist offensive had been anticipated but the size and intensity had not. A large scale air campaign against North Vietnamese military targets and supply lines was initiated to neutralize and halt the invasion. The operation was named Linebacker I.

It was during this air campaign that Lt. Jack Stice and Lt. Bobby Long arrived at DaNang. Stice, while on his “in-country” checkout made his first save. An

(LT Stice is in the “Snoopy” Cap)

Air Force F4 was severely damaged by enemy ground fire about 15 miles southwest of Hue. Describing the incident, Captain Jim Beaver, the F4 pilot, said, “We were hitting enemy troop locations and got hit with automatic weapons fire. The airplane still flew alright and we made for the ocean and turned for DaNang. However, my backseater, Lt. Andy Haskel, noticed a small fire. An explosion followed and we ejected.” Stice and his crew saw the ejection and proceeded directly to the survivors and picked up both men. They were in the water less than 15 minutes. A similar pickup was made by Stice several weeks later. An F-4 had been shot up and had managed to get “feet wet” –barely. Capt. Boroczk, pilot of the first Jolly picked up the F4 pilot and Lt. Stice, in the number two jolly, picked up the backseater. 1stLt. Mike McDaniel, Lt. Stice’s co-pilot, said, “We went for the second man as the PJs were arming the mini-guns. We went into a normal Coastie hover,* Sgt. Hammock ran the hoist down right next to the pilot and we fished him out of the sea.”

* The Army began training Air Force helicopter pilots at the end of 1970. For the first time, Air Force pilots were being trained with no previous fixed wing time. The helicopter pilots started at Ft. Rucker and then to Ft. Wolters. From there the HH-53 pilots went to Hill AFB for transition and combat crew training. Over water operation was not part of the training. In 1972, new, low-time, pilots were arriving at the 37th directly from initial training. Lt. Stice and Lt. Long both said that they spent many hours teaching the newbies how to establish a stabilized hover using a visual reference point independent of the wave action; — then once established, make small corrections as directed by the hoist operator who was on a hot mike. The Air Force pilots in the squadron referred to this as the “normal Coastie hover”.

Not everyone was able to reach the relative safety of the ocean. Such was the case for Nail 60, an OV-10 FAC. The

crew ejected close to the Laotian/South Vietnamese border about 40 miles southwest of Hue. Nail 36 was in the area, acted as on scene commander and directed the rescue aircraft in. Low ceilings and high mountainous terrain were a hindering factor. Four Sandys and two Jollys were launched. Upon arrival, Sandy 07, assumed duties of on scene commander. Radio contact was made with Nail 60A. He was ok but Nail 60B was injured and could not move away from his chute. Jolly Green 65 and 66 arrived on scene 30 minutes later with the weather still marginal. Jolly 65 was low bird, Lt. Long USCG was the aircraft commander. A visual was obtained on Nail 60A and Jolly 65 headed in with a Sandy escort. Pick up was made with a minimum of hostile opposition and Jolly 65 proceeded to bravos position. Nail 60B was known to need assistance so the PJ, Sgt. Caldwell, went down with the penetrator. It was determined that bravo had a broken back and a litter was requested.

Long put the helicopter right down into the trees to minimize target presentation and as the litter was being lowered his crew reported a group of armed men approaching the aircraft . He relayed this to the Sandys who took them out. The Sandys then set up a race track pattern to suppress any further incoming fire. Twenty minutes transpired from the time the litter went down to the time Bravo and Caldwell were on their way back up. All this time Long maintained his hover. He said, when fired upon, they returned fire with their mini guns but it was the Sandys that made the rescue possible. Without them it could not have been done. (26)

The Linebacker I campaign was very successful. By mid-October, with depleted war materiel and stalled invasion, North Vietnam communicated its willingness to negotiate a peace agreement. President Nixon terminated the operation to signal his cooperation. On 30 November 1972, official word was received that the 37th ARRS was being de-activated. About a third of the aircrews were reassigned to the 40th ARRS at NKP. Lt. Jack Stice USCG, although junior in rank, was selected to plan and execute the transfer of men and aircraft to NKP. This was questioned by the 3rd Group but Lt. Col. Sutton was firm in his decision stating that Lt. Stice had the experience, was the most qualified to do the job, and that rank was not the primary consideration.(27)

In mid December, North Vietnam created intransigence at the peace talks. President Nixon sent Hanoi an ultimatum to come back to serious negotiations. The ultimatum was ignored and on 18 December Operation Linebacker II was launched to intimidate North Vietnam. In 11 days of devastating bombing most of the desired targets were destroyed, breaking down the war making capabilities of North Vietnam. It was an around the clock operation using large numbers of B-52s and five US Navy aircraft carriers. After years of restrictive engagements, US air power was finally allowed to demonstrate what it could do. (28) In Linebacker II, the US lost 15 B-52s and 12 other aircraft. The overall loss rate was below two percent. (29) The Jolly Greens rescued 25. Forty-one were captured by North Vietnam. Because the targets were in highly defended areas, not one crew member was picked up in North Vietnam. There were limits as to what the helicopters – even the giant HH53s – could take, but that didn’t mean the Jollys did not try. (30)

On 23 December, Jackel 33, a F-111 was shot down in a karst area 17 miles southeast of Hanoi. Beepers from both pilots were picked up on the 24th and rescue forces were launched. The mountains were protruding through a solid undercast which precluded strike aircraft from delivering ordinance and any pick up attempt. Both alpha and bravo pilots were advised to move to higher ground, stay well hidden, and come up on their survival radio whenever Fast Movers were heard. Weather again precluded rescue attempts on the 25th and 26th. Weather cleared on the 27th and Jolly 73 and Jolly 66 launched for the rescue area. They refueled with King 27 and rendezvoused with the Sandys just inside the North Vietnamese border. The helicopters started the final run to the rescue area with Capt. Dick Shapiro in Jolly 73 in the lead and Long in Jolly 66 in trail. Jolly 66 was instructed to hold 15 miles out with Sandy 03 as cover. Shapiro said that a half mile out he could see the karst area where Jackel 33B was located. It rose about 2000 feet with a gentle slope to the top. About two thirds of the way up the slope they began taking heavy 51 caliber fire from the right. Shapiro could see the tracers go past the nose and one of the Sandys reported fuel streaming from the right side of the aircraft. The survivor was on a ledge covered with tall elephant grass. A1C Jones fired his minigun into the gun position silencing it. Jackel 33B popped smoke and Shapiro came to a hover over him. By this time they were taking fire from all sides. As the penetrator was being lowered they took a number of AK-47 rounds in the cockpit from surrounding trees. The co-pilot, Capt. Pereira, was hit and they continued taking fire from underneath the aircraft. Jolly 73 was zeroed in and the survivor had not climbed on the penatrator. Shapiro executed an immediate egress to the right and down the hill. He said the helicopter went into an almost uncontrollable oscillation which smoothed out as his airspeed went through 80 knots. Shapiro surveyed the damage. He was getting surges in both engines, the hydraulic system was indicating minimum pressure and oscillating, he was getting yaw kicks, the radar altimeter was out and the UHF radio was intermittent. Long volunteered to go in for another attempt but it was decided that given the present conditions, there was no way a rescue attempt would be successful.

Long followed Shapiro out and handled radio communications for him. He informed King that Shapiro would need fuel and to meet them. When Jolly 73 tried to extend the fueling probe it would not budge. Shapiro tried to refuel without the probe extended. As soon as contact was made fuel started streaming from the probe and he got a disconnect. Fuel was critical and Jolly 73 was going to have to find a place to land. Long in Jolly 66 had been monitoring the situation and had already picked out an area and directed Shapiro to it. When Shapiro retarded the throttles for landing all power was lost and the rotor blades began oscillating badly. The crew was out of the aircraft within 30 seconds after touchdown.

In Capt. Shapiro’s mission summary he states the following; ” I can’t give enough credit to Capt. Long. * On egress I was having communications problems. Capt. Long took care of communications for me. Realizing that I would have to land in mountainous terrain because of impending fuel starvation, Capt. Long scouted ahead of our route of flight for a possible secure landing area. When I made the decision to land the aircraft and requested assistance, Capt. Long was already hovering over a spot not more than a mile away. As I entered the area, he began talking me into touchdown. He landed shortly after I touched down, as close as possible to us. His crew had us on board within a short period. Had it not been for his invaluable assistance, our crew would have been engaging enemy personnel during the next few hours.”

A short time later a Jolly Green that had been orbiting as back up tried to land in order to salvage equipment. They came under fire from a group of 50 or 60 people and quickly exited the area. A Sandy flight was called in and the helicopter was destroyed. (31)

* In the Mission Summary Capt. Shapiro referred to Lt. Long by his Air Force equivalent rank. This was later corrected.

Major General Don Shepperd USAF (Ret) was a Misty FAC pilot during the war in Vietnam. He tells of a F-4 that went down in the Ashau Valley. Shepperd ,

Misty 34, was on scene with Misty 21 and two Sandys. The F-4 back-seater had a broken leg was down on the side of a mountain overlooking the valley. One Jolly Green was maneuvering to pick him up. The front-seater was OK, down in the middle of the valley. His collapsed chute was clearly visible and the NVA had him surrounded. He was calling for ordnance to be put right next to his chute and said the ‘bad guys’ were all around and coming closer.

Sandy lead directed the Mistys to fly a north-south pattern. The Sandys were working east-west. The pilot was 50 meters west of his chute with the enemy closing in. The patterns were timed so that a Misty was rolling in just as a Sandy pulled off resulting in max ordinance being delivered to the target area on a sustained basis. Shepperd noticed the lead Jolly was now in a hover about one mile east of his position. The PJ was being lowered on the hoist to assist the injured pilot. A short time later, while on a downwind leg, he again glanced towards the hovering Jolly that was picking up the back-seater. The Jolly was being hit repeatedly by gunfire. He heard the Jolly pilot tell Sandy lead in a calm voice, “We’re picking up some hits —- We’ll be out of here in a couple of minutes.” He was cool as ice.

PJ about to be hoisted up with injured man. This was the most vulnerable time for the helicopter. On many missions the North Vietnamese would wait for this moment and direct maximum firepower at the Jolly Green.

When Shepperd heard this he cut loose with a few choice words of admiration! He went on to say, ” This guy had a set! We continued our passes over the downed pilot and on each downwind I looked at the helicopter. I watched him on four patterns, and although I didn’t count, I’m sure he was hit 20-30 times just while I was watching. Courage is a core competency often ascribed to the military. Its synonym bravery is associated with fighter pilots — most of the time by the fighter pilots themselves – but this day I knew who owned the title –bravest of the brave – JOLLY GREEN PILOTS! -hands down, bar none, no contest!” (32)

Where did these men get the courage to go out almost daily for a year knowing that hostile forces were waiting to kill them each time they went? Mixon did not know, other than to observe that some found strength in religion, some found it in drink, and others in themselves. Only those who have willfully place themselves in harms way and experience the deep innermost feelings which come from saving another’s life can truly understand. (33)

Fear was present – it did not go away, but a brave man can control it and even use it to his advantage. Without fear there is no courage. Butchka said each time he got ready to go his mouth felt dry and he found speaking was an effort but once into the mission, this would disappear. (34) The Jolly Greens were determined to make the save. The “Bad Guys” were determined not to let it happen.

The Air Rescue forces in Southeast Asia didn’t get all of the downed airmen but no one can say they didn’t try. They did get 3.883 (35) and provided the world with thousands of examples of unselfish humanity. A report prepared by the Air Force Inspection and Safety Center, summarizing helicopter use in combat rescues, noted that during the Vietnam War, between 1965 and 1972, helicopters came under significant hostile fire in 645 opposed combat rescue operations involving downed aircraft. Crews were rescued in six hundred, or 93 percent, of these cases. This was not accomplished without cost. The 37Th ARRS lost 28 men including Lt. Jack C. Rittichier USCG.

The Coast Guard aviators who served on the rescue team were highly praised by many. They stated that their exceptional proficiency was a product of their motivation to save lives, rather than individual brilliance. They no doubt downplayed themselves to avoid sounding boastful, but the commendations and awards presented to them proved not only their incentive, but most certainly their flying skills and bravery as well. This group of men were awarded 4 Silver Stars, 16 DFC’s, and 87 Air Medals.

Their numbers were not large — Their contribution was. They were all volunteers who regularly put their lives on the line to save fellow airmen who were in peril of death or capture. The focus was on duty, honor, country, and Coast Guard. Their mission was noble. They were much more than participants — they were heroes. Their performance brought honor upon themselves, Coast Guard Aviation and the United States Coast Guard. History should ever reflect their honorable actions.

Silver Star Medal

For distinguished gallantry in action against an enemy of the United States or while serving with friendly forces against an opposing enemy force. The Silver Star is the third highest military award designated solely for heroism in combat.

Distinguished Flying Cross

The Distinguished Flying Cross is awarded to any person who, while serving in any capacity with the Armed Forces of the United States, distinguishes himself or herself by heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight. The performance of the act of heroism must be evidenced by voluntary action above and beyond the call of duty. The extraordinary achievement must have resulted in an accomplishment so exceptional and outstanding as to clearly set the individual apart from his/her comrades or from other persons in similar circumstances. Awards will be made only to recognize single acts of heroism or extraordinary achievement and will not be made in recognition of sustained operation activities against an armed enemy.

Air Medal

The Air Medal is awarded for to any person who, while serving in any capacity in or with the Armed Forces of the United States, shall have distinguished himself/herself by acts of heroism or meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight. Required achievement is less than that required for the Distinguished Flying Cross, but must be accomplished with distinction above that expected of professional airmen. Awards may be made to recognize single acts of merit or heroism, or for meritorious service.

Purple Heart Medal

The Purple Heart is awarded in the name of the President of the United States to any member of an Armed Force who, while serving with the U.S. Armed Services after 5 April 1917, has been wounded or killed, or who has died or may hereafter die after being wounded; (1) In any action against an enemy of the United States; (2) In any action with an opposing armed force of a foreign country in which the Armed Forces of the United States are or have been engaged;

Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry With Silver Star

This is an award presented by the Republic of Vietnam to an individual who while serving with or in conjunction with the Armed Forces of the Republic of Vietnam while engaged in action against an enemy displays exceptional gallantry of marked distinction.

Vietnam Medal Recipients

Lt. Richard V. Butchka

Distinguished Flying Cross (2)

Air Medal (6)

Lcdr. Joseph L. Crowe

Distinguished Flying Cross (2)

Air Medal (9)

Lt. Lance A. Eagan

Silver Star (1)

Distinguished Flying Cross

Air Medal (11)

Lt. Thomas F. Frishmann

Air Medal

Lt. Robert E. Long

Distinguished Flying Cross (2)

Air Medal (8)

Lt. James M. Loomis

Air Medal (8)

Lt. Roderick Martin

Air Medal (7)

Lcdr. Lonnie L. Mixon

Silver Star (1)

Distinguished Flying Cross (1)

Air Medal (10)

Vietnamese Cross of Galantry (1)

with Silver Star

Lt. James “Casey” Quinn

Distinguished Flying Cross (1)

Air Medal (8)

Ltjg. Robert T. Ritchie

Silver Star (1)

Distinguished Flying Cross (2)

Air Medal (7)

Lt. Jack C. Rittichier

Silver Star (1)

Distinguished Flying Cross (3)

Air Medal (3)

Purple Heart

Lt. Jack K. Stice

Distinguished Flying Cross (1)

Air Medal (8)

1. Tilford, Earl H. Jr. : Search and Rescue in Southeast Asia 1961-1975.

2. Baylor Haynes Seminar: Jolly Green Reunion, 4 May 2002.

3. Westerman, Edward: Air Rescue Service and Direction for the Twenty First Century.

4. LaPointe, Robert: Vietnam SAR Chronology, 6 September 2002.

5. Beard, B.T. : Vietnam Experience, compiled 1994.

6. Ibid 2.

7. Commandant (O) letter to Lcdr. John E. Moseley dtd. 3 March 1966.

8. Ibid 1.

9. Commandant (PO) letter to Lcdr. Lonnie M. Mixon, dtd. 28 July 1967.

10. Frischmann, Thomas F.: Narrative account of USCG-USAF Pilot Exchange Program — 8 November 1967 to 2 June 1970.

11. Rittichier, Jack C. : Coast Guard Activities Vietnam News Letter, June 1968.

12. Kroll, Douglass: Jack C. Rittichier; Coast Guard Aviation Hero, Naval Aviation News, November-December 1991.

13. Interview with Lonnie L. Mixon.

14. 37th AARS Mission Narrative 1-3-63, 9 June 1968

15. Ibid 1.

16. Ibid 13.

17. Shershun, Carroll S.: The Lifesavers, USCG Aviation, supplemented by Mission Evacuation Report, A1C Joel Talley – (68-07-02).

18. Mission Narrative summary 37th ARRS (1-3-02- 8279), 5 October 1968.

19. Commander Coast Guard Activities, Vietnam news release # VN 75-68. Interview with Lt. Col. Charles R. Klinkert, USAF, Commander 37th ARRS.

20. Interview with Rob Ritchie.

21. Interview with Casey Quinn.

22. Interview with Dick Butchka.

23. 37th ARRS History Summary 1 July – 30 September 1971.

24. Ibid 23.

25. Sturm, Ted: The Miracle Mission , Airmans Magazine August 1973.

26. Interview with Bobby Long.

27. Interview with Jack Stice.

28. Trong Q Phan Phd: Analysis of Linebacker II, 01 Mar. 2002

29. Linebacker II USAF Intelligence Summary 30 June 1973

30. Ibid 1

31. Mission summary 40-1333 27 Dec ’72 – supplemented by interview with Bobby Long

32. Shepperd Don: Bravest of the Brave

33. Ibid 13.

34. Ibid 22.

35. Ibid 1