Author: by CAPT Jeffrey D. Hartman, USCG (retired)

Reprinted with permission from the Coast Guard Academy Alumni Association, The Bulletin, May-June 1985

Rescue Crew

HH-52A #1353 (Duty Crew): LT Glenn Gunn (AC); LTJG Al Seidel (CP) and AD2 Jeffrey Patenaude (FM)

HH-52A #1383: CAPT Jeffrey Hartman (AC); LT Tom Bell (CP) and AE3 Ted Nelson (FM)

When the phone rang at my Oregon home that Sunday evening and CDR Pat Wendt said, “Can you Fly?, “I knew something big was up. What Pat was really asking was had I been enjoying a beer with the golf match that I’d been watching on TV. Fortunately I hadn’t, and I “could.” At the time I was Deputy Group Commander at Group North Bend, Oregon and Pat (now Group Cdr. Group Cape May) was the Group Operations Officer. He asked that I come into the Air Station ASAP and he would brief me once I was there. I didn’t argue with him because I knew if he was calling me it was something serious.

North Bend, Oregon is the location of the Air Station and Group Office of the same name. The Group includes six coastal SAR stations, an Aids to Navigation Team, an ESMT shop and the Air Station. Covering the southern two-thirds of the Oregon Coast, we prided ourselves on operational excellence. Others apparently agreed with us in that assessment, as that year the third Navy League Munro Award winner in a row, had come from our Group’s Officers-in-Charge. The SAR case on 7 June 1981 was to tax many of us to the limits of our capabilities.

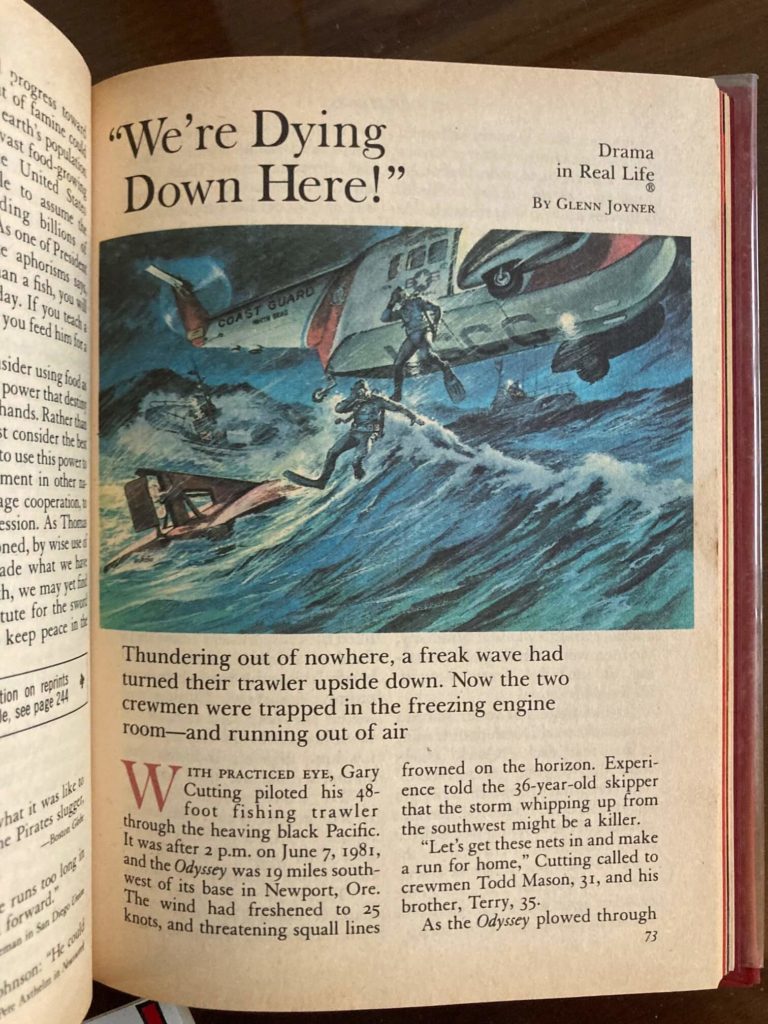

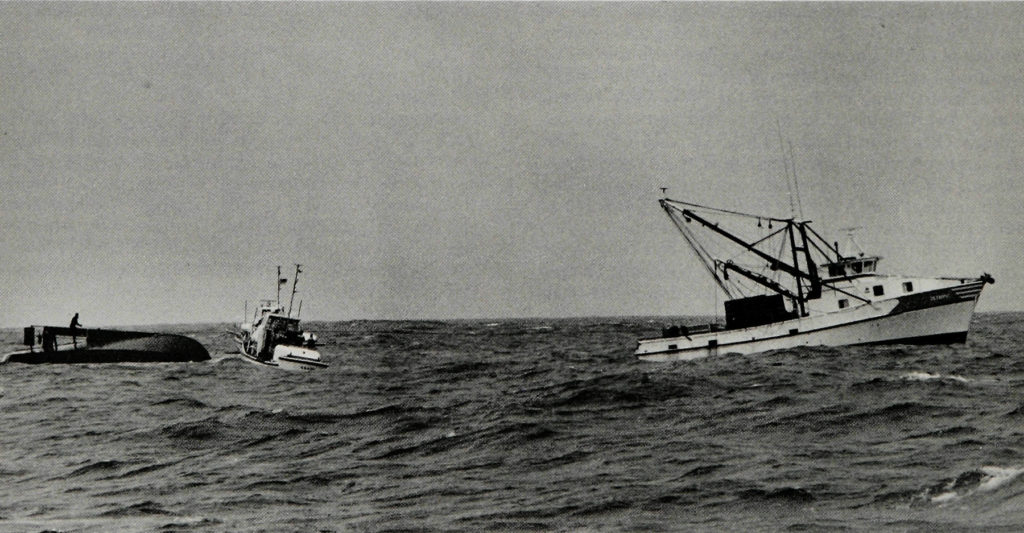

Once I got into the operations center, Pat began telling me an unusual tale. A fishing vessel, the TRIUMPH had radioed the Coast Guard Life Boat Station at Yaquina Bay, Oregon that, in a bad storm, they had come upon a capsized 48′ vessel 12 miles south of Newport, Oregon Yaquina had sent out one of their 44′ motor life boats (MLB) and the Air Station had launched the duty helicopter HH-52A, CGNR 1353. The pilots, LT Glenn Gunn and LTJG Al Seidel flew the 60 miles north to scene in rapidly worsening weather. Once on scene they noted the weather to be low ceilings, winds of 35 knots gusting to 45, and seas of 14 feet. Heavy rain showers in squalls further reduced the visibility.

Both the MLB and helo searched in the immediate vicinity of the capsized hull for people in the water, with negative results.

The two pilots, perhaps with an image of a mini Poseidon Adventure in their minds, asked for a volunteer from the MLB to be hoisted onto the hull to check for any sounds of life inside. Petty Officer Craig White agreed to try it and he was subsequently hoisted from the relative safety of the 44 footer to the slippery bottom of the pitching hull. By now we had determined the name of the vessel to be the ODYSSEY. At 2030, clinging to what he could, White began systematically banging on the ODYSSEY’s hull.

Suddenly White began hearing answering banging from inside. He excitedly signalled the helicopter that there were people trapped. As the word was radioed back to operations, many minds began pondering the problem of what to do. Trying to right the hull, given the on scene conditions, seemed out of the question. Cutting through the hull with torches was considered but that entailed the chance of losing the trapped air, possibly sending ODYSSEY and the person(s) inside her to the bottom. Using divers to attempt to bring out the survivors seemed to be the most realistic and timely solution.

At Yaquina Bay Station, BMC Garrison, the Officer-in-Charge began making phone calls looking for divers who would be willing to attempt the rescue. Back at the Group Office Pat Wendt was now doing the same thing. Chief Garrison finally located two local Newport divers who were willing to go to the scene to assess the situation. Group OPS directed the helicopter (CGNR 1353) to depart scene for the Newport Airport to do the transport. This was the status of the case when I arrived at the Group Office and was briefed.

Pat, and the Group Commander, CAPT Frank Olson had elected to send a second helicopter to the scene as backup and to provide illumination with the night sun” search light which was being installed on the second helo. After the preflight preparations were complete I, and my copilot LTJG Tom Bell and crewman AE3 Ted Nelson departed for the scene just before sunset in a helicopter, HH52A, CGNR 1383.

Enroute we talked to the other helo, CGNR 1353 turning up at the Newport Airport. LT Gunn estimated that the two helos would be arriving on scene at about the same time and he briefed me on the adverse weather. I told him that we would let down several miles to seaward of the distress and let him come directly in with the divers.

The next event was disappointing. Once on scene the Newport divers said the dive would be too dangerous and declined to make the attempt. LT Gunn radioed this info back to Group OPS where Pat and CAPT Olson were coordinating the case.

Pat had earlier talked to two Coos Bay divers, Bill Shires and Pat Miller of All Coast Commercial Divers. They had said that they would help if needed and had come into the Air Station with all their gear. Pat had also arranged with a local charter pilot, Art Tiller, to standby to fly the divers to Newport in his twin Seneca Piper. This would save more than an hour over what it would take to have one of the on scene helos return to North Bend for the pickup.

Group OPS directed the two helos on scene to return to Newport with the first dive team to await the arrival of the second team and to refuel. As Gunn and Seidel were approaching their allowable flight time due to having flown on two previous cases earlier that day, they were directed to return to North Bend where a fresh crew would be assigned. CAPT Olson and LCDR Sistek were standing by to man CGNR 1353 upon its return.

Meanwhile Chief Garrison was besieged by people wanting to assist with the case. The word had spread rapidly in the small fishing community and people were gathering at the airport to await word of the situation.

Mountains of equipment were accumulating, being brought by volunteers in case it might be needed. One person who was a big help was Roger Vance who owned a sister ship to ODYSSEY. He was rushed to the airport to meet with Shires and Miller upon their arrival, to describe the internal layout of the ODYSSEY.

Once back at Newport Airport I sent my copilot into the flight line office to await the divers and escort them to the 1383. Petty Officer Nelson and I refueled the helo by flashlight in the rain and then remanned it so that I could get it started as soon as Tiller’s aircraft arrived. I was concerned that the Seneca Piper might have problems landing as the ceilings were getting progressively lower as the cold front approached. In the best bush pilot tradition Art made it. (He was later to receive a Public Service Commendation for his part in the rescue.)

Once I saw the aircraft land I cranked up the helicopter and awaited the divers and my copilot. After receiving their briefing the party came to the helo assisted by about twenty volunteers carrying equipment. I had to hold what we took to the essentials due to the weight limitations of the helo. I had already reduced the fuel load to accommodate the five persons on board and what I estimated to be the weight of their equipment (which I had gotten by radio from Pat Wendt back at North Bend.)

We departed back to scene shortly after midnight. Enroute, Shires and I talked on the ICS concerning his delivery. It was decided that the divers would enter the water in the near vicinity of the ODYSSEY from a low hover. We would then transfer by hoist their extra air bottles and equipment to one of the on scene 44′ MLBS.

Arriving on scene we found another pleasant surprise. Although the weather was still rotten, the assisting armada had been joined by a commercial crabber, the RHONDA, whose high intensity search lights were a great aid for everyone. Tom and I briefed for and then executed a straight-in instrument approach to the water called a “Beep to a Hover.” Once safely established alongside the capsized hull I timed the 14 foot swells and told Nelson to tap the divers on my signal to enter the water. Once they were both safely in the water we prepared to transfer the remaining equipment.

We directed one of the 44 footers to break off and get underway with the wind on its port bow. This put the MLB bow-on into the seas as well. This turned out to be one of the toughest hoists I’ve ever made. Because the boat was surging in the heavy seas I briefed for a trail line delivery of the spare air bottles which weighed about 50 lbs. each. Nelson lashed three of them together and we delivered the trail line. With the seas causing the boat to rollercoaster and with the weight of the bottles Nelson had a hard time keeping them from swinging and I had a hard time keeping over the boat without losing visual reference. At one time the trail-line wrapped around the MLB mast and was freed only by some heroic actions on the part of one of the boat’s crewmen. After several attempts, we backed off and decided for a non-direct delivery. We once again passed the trail-line and then backed off to the boat’s port quarter. When the seas were right, Nelson pushed the bottles overboard where the MLB crew pulled them in. By now we were getting low on fuel and we departed for Newport to refuel.

The 40 knot tailwind made for a short flight but approaching the coast we became more and more uneasy. The ceilings were getting progressively lower and with about 3 miles to go on the Tacan we found the 161 ft. elevation runway to be socked in fog. At about the same time our fifteen minute fuel light came on. I knew that shooting the non-precision approach would be fruitless. We considered going to a helo pad at the Yaquina South Jetty where a fuel truck could reach us but that could take hours. It would also mean a down wind flight two miles at night with 100′ ceilings and a 35 kt tail wind. We decided to land on the beach abeam the tacan to conserve fuel and discuss our few alternatives.

Tom Bell suggested using the night sun to hover up the cliff, cross highway 101 over the trees, homing in on the Tacan at the field. This seemed like the best option we had that would get us back into the action. With me flying the hover into the wind and with Tom working the search light we started up the cliff into the fog. It turned out to be relatively simple and except for a TV crew turning its lights on us just as we hovered into the ramp, it worked great. We quickly refueled and headed back to the scene at about 0200.

Meanwhile, Miller and Shires were having some problems of their own. With the capsized hull pitching in the black seas and rolling 35 degrees the operation was a little on the dangerous side to say the least. None of us knew if the boat would lose its “air bubble” and go to the bottom. Adding to the dangers, the divers found the underside of the boat completely wrapped in its own nets which they had to methodically cut away. Once inside the wheel house they found it jammed with floating gear. Again they used precious time and air removing it piece by piece so that it wouldn’t block their exits. No one knew for sure how many people were trapped nor if they were still alive. After working for an hour, Shires had not located the survivors and was running out of air. Surfacing, he and Miller swam to the 44 footer for fresh bottles.

Learning from the 44 footer crew where the taps had been heard inside, Miller and Shires swam back to the ODYSSEY. They climbed on the hull and again began tapping. Over the port side of the engine compartment they got their response.

Figuring that the survivor(s) would not have any diving experience, the divers rigged a tag line with chemical lights every few feet. This line was then led from the “exit” in the net to the wheelhouse and “up” to the engine compartment hatch. The hatch was closed and difficult to move with the water on top of it. Shires finally got it opened and saw a hand reaching down to help him. His classic remark as he surfaced in the greasy water of the engine room to the two survivors (brothers Todd and Terry Mason) was, “I bet you’re glad to see me.”

The problem was not over however. “Murphy” had once again entered the picture. In entering the jammed hatch to the engine room Shires had ripped a hole in his regular hose and had now lost all his air. Not wanting to frighten the brothers anymore than they were already, Bill told them he had to go for more equipment. Holding his breath, praying that he didn’t get hung up, he worked his way back along the tag line, through the “exit” in the net, to the surface.

Returning to the 14 footer. Bill got a fresh tank and the Pony bottles for the brothers. Back inside he gave his two apt students what he called the quickest diving lesson on record. Then one by one Shires led them to safety. A swimmer from the 14 footer entered the stormy sea to assist the hypothermic brothers and the now exhausted Bill Shires. The time was 0342.

One of the greatest feelings of my life was seeing the brothers come to the surface as we hovered over the hull with our night sun. We radioed the good news back to the airport where the helicopter CGNR 1353 with CAPT Olson and Rick Sistek was turning up as a backup. The word spread like wildfire through the small fishing community. The news was not all good though as a third member of the ODYSSEY crew, skipper Gary Cutting, was never located.

On 5 November 1981, Bill Shires and Pat Miller received the Gold Lifesaving medal from RADM Clifford F. Dewoll, Commander Thirteenth District in ceremonies at the North Bend Group Office. A tragic footnote is that, eight days later CAPT “Ollie” Olson lost his life when helicopter 1353 lost its engine off shore, at night, on another rescue mission during the terrible Friday the Thirteenth storm.