By J.R. Lee, AOC, USCG (Ret) and Ted A. Morris, Lt.Col., USAF (Ret)

Late in the afternoon of April 16, 1950, William Strecker and Gus Detrick of Miami, FL made ready Strecker’s 35-foot cabin cruiser, Moonlight, for an evening of fishing about 30 miles south of Miami. Their destination was south of Cape Florida, near Elliot Key at the south end of Biscayne Bay. The most important thing Mr. Strecker did was to inform his wife of where they were going, and when they would return.

At almost the same time that day, another boat prepared to leave Miami. Mrs. Rosa Pent, her 16- year old daughter, and friends Mr. and Mrs. Chester Smallwood, and Mrs. J.D. Howard decided to take a late evening cruise in the Howard’s 18-foot speed boat, Butch. They did not notify anyone of their plans, where they would be, or when they would return. Afternoon became evening, then night. In the pre-dawn of April 17, 1950, Mrs. Strecker, concerned about her husband’s continued absence, called the Coast Guard’s emergency telephone number for the Miami area. She was quickly connected to the 7th Coast Guard District’s Rescue Coordination Center (RCC), which quickly set into motion a search for Moonlight and its occupants.

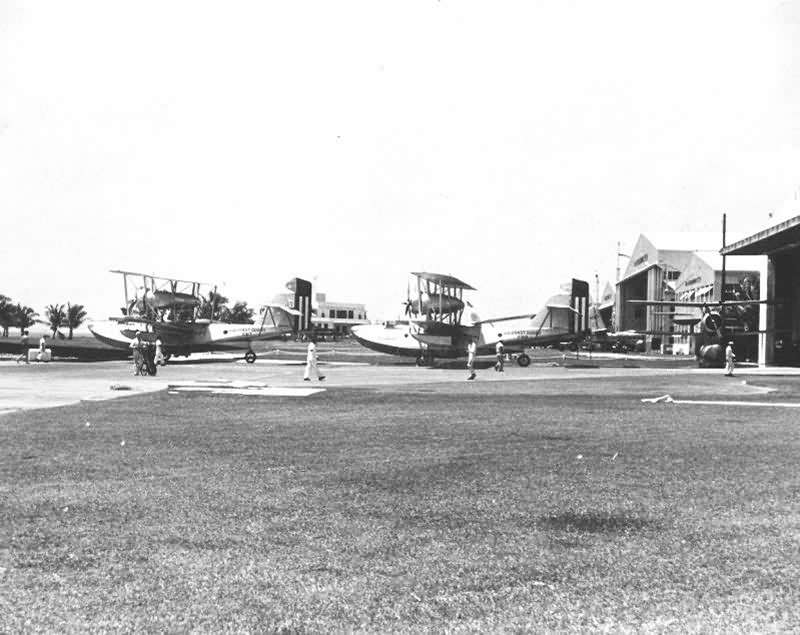

Miami Coast Guard Air Station at Dinner Key was the station tasked with the search. The Air Station was adjacent to the pre-W.W.II Pan American World Airways “Seadrome,” and the Coast Guardsmen there made ready their Grumman JRF-5, Bureau Number 37804 for launch. The JRF-5 was a twin-engine amphibian with a cruising speed of 150 mph and able to remain airborne during a search for about five hours. Pilot LT.(JG) C. R. Leisy, Aviation Chief Radioman (ALC) Halstead, and Aviation Machinist Mate Third Class (AD-3) Paul Freund were the crew that morning. With AD-3 Freund in the copilot’s seat as a searcher, LT. Leisy taxied down the seaplane ramp and made a water take off at first light.

Armed with the knowledge of the general area to which the Moonlight had been bound, LT. Leisy, a veteran of numerous such rescue operations, began the search. He flew a fairly standard search pattern – beginning at the most probable location of the vessel, and flying an ever enlarging box pattern to locate the boat. After nearly two hours of searching, Radioman Halstead sighted a vessel as they passed southeast of Cape Florida between Key Biscayne and Elliot Key. Lieutenant Leisy flew down close to the water’s surface and was able to identify the cruiser as Moonlight by her name across the stern.

He notified the RCC by radio that the vessel appeared to be disabled and drifting, but that the two occupants appeared to be okay. He requested a surface vessel be sent to aid the Moonlight back to port, and the RCC dispatched a 38-foot picket boat from the MacArthur Causeway Coast Guard Base to perform that duty.

Since they had no radio contact with the Moonlight, LT. Leisy had AD-3 Freund drop a message to Strecker and Detrick that help was on the way. He did this using a wooden “message block” which had a long yellow streamer attached. Receiving an O.K. signal from the Moonlight, Leisy then flew north toward the Coast Guard Base on the causeway, making radio contact with the 38- foot picket boat. He gave the picket boat’s crew the location of the Moonlight and a compass heading for a successful rendezvous. He then flew back to the Moonlight and dropped an MK6 smoke light near the inoperative vessel. The MK6 would give a 45-minute long smoke signal for a visual reference for the picket boat’s crew as they drew near. Having ensured the rescuers and the Moonlight would rendezvous, and with over half his fuel expended, LT. Leisy set course for the Dinner Key Air Station, having performed a good morning’s work.

Minutes later, crew member Freund shouted,”Lieutenant, there are four people down there in the water.” Lieutenant Leisy immediately banked the JRF around and soon sighted four survivors of the Howard’s speed boat, Butch. Late in the evening of April 16th, while Joanne Pent was steering the boat, it apparently struck an underwater obstruction, tearing the bottom from the speed boat and throwing the five occupants into Biscayne Bay. The Butch sank immediately, and the survivors managed to cling to the engine cover and several buoyant cushions which had floated to the surface. By the time they were spotted by AD-3 Freund, they had been in the chilly water for over 14 hours.

Had it not been for the remarkable coincidence and professional Coast Guard aircrew, they all would have died in the water. No one knew they had gone boating, where they went or when they would return. In fact, no one knew that they were missing! Lieutenant Leisy recognized a life or death emergency when he saw one and he immediately notified RCC of the situation and set up for a water landing. Taxiing up close, he noted that the survivors were too weak to swim to the aircraft, and rightly suspected they were in fact too weak to fend off the airplane’s hull if he attempted to taxi to them. To avoid injuries, Freund stripped to his shorts and, taking a rescue lifeline, plunged into the bay, which is pretty cold in April. Freund swam to the group and grabbed hold of the engine hatch cover to which the survivors clung with their last bits of strength. He then signaled Leisy and Halstead to pull them to the aircraft. The survivors were all suffering from hypothermia and were almost completely unable to assist in their own rescue.

After considerable work, the Coast Guard crew got the four survivors on board the aircraft. Unfortunately, they were not in time to save Joanne Pent’s mother, Rosa. An hour before they were spotted, the older Mrs. Pent had weakened to the point where she could not hold on any longer, and the other survivors were too weak to help, and she sank beneath the surface. Lieutenant Leisy knew the survivors needed immediate medical help. Before attempting to depart, he placed two MK6 smoke lights in the water to mark the location for a boat search for Rosa Pent. He then attempted a water takeoff, but the JRF was overloaded and he could not get airborne. The only alternative was to set course for a long water taxi back to the Air Station at Dinner Key. Applying full power to the two engines, Leisy got the JRF up “on the step” and started a high speed taxi to the Air Station. Radioing ahead, Halstead arranged for ambulances and medical personnel to be on hand to take the survivors to Miami hospitals. Meanwhile, RCC sent a 30-foot crash boat from Dinner Key Air Station to the area to pick up debris and search for Mrs. Rosa Pent. The search crew recovered Mrs. Pent’s body about an hour later.

Thanks to Mr. Strecker’s information to his wife, and the professionalism of LT. Leisy and his crew, six more names were added to the Coast Guard’s long list of lives saved. Lieutenant Leisy, Radioman Halstead, and Aviation Machinist Mate Freund each received a Letter of Commendation for their outstanding professionalism during their lifesaving mission of April 17, 1950.