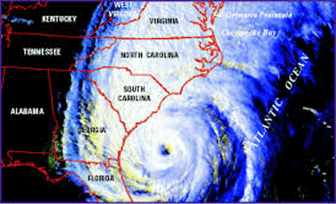

In September 1999, Hurricane Floyd – a Category 4 storm, with peak winds of 135 mph, struck the East Coast of the United States. Floyd triggered the fourth largest evacuation in U.S. history when 2.6 million coastal residents of five States were ordered to evacuate from their homes. Originally forecast to cross the State of Florida, the storm turned north.

In September 1999, Hurricane Floyd – a Category 4 storm, with peak winds of 135 mph, struck the East Coast of the United States. Floyd triggered the fourth largest evacuation in U.S. history when 2.6 million coastal residents of five States were ordered to evacuate from their homes. Originally forecast to cross the State of Florida, the storm turned north.

Heavy rain began moving across the eastern Carolinas during Tuesday September 14, expanding in coverage that night and continuing into the next day. A stationary front lying across the eastern portions of North and South Carolina helped lift the increasingly humid onshore winds, sustaining heavy rainfall. By the time tropical storm force gusts began in Wilmington NC on Wednesday afternoon, over six inches of rain had already fallen. Floyd’s eye had turned northward as the storm passed off the east coast of Florida and Georgia. This lined the storm up for a direct impact on Cape Fear NC. Landfall occurred at 2:30 a.m. on Thursday morning, September 16, 1999.

Coast Guard Air Station (CGAS) Elizabeth City’s first response efforts began at 09:30 am, 16 September when a call came in requesting a MEDEVAC from the M/V Huge Dyke, a container ship, fighting high winds and seas. The ship was about 210 miles east of Elizabeth City N.C and was reporting 70 knot winds and 30–50-foot seas. The conditions had caused a stack of 6 semi-truck sized containers to topple, severely injuring a crewman. HH-60J CG6026 crewed by LCDR Glen Freeman (PAC), LT Koester (CP), AMT1 Ken Laffey (FM), and AST3 Shane Walker (RS) successfully rescued the ship’s crewmen, and delivered him to Norfolk Sentara Hospital. This was a difficult rescue and an omen of things to come.

Immediately after the passage of the Eye of the hurricane, CGAS Elizabeth City launched a HH60J helicopter to complete an aerial survey of the area and to provide assistance to those in distress. No one knew when the first few were rescued that the number needing rescue would grow into the thousands. Later that night, the incredible magnitude of the flooding was realized, Reports of hundreds of victims stranded on rooftops, in cars, on highways, in trees, and in rivers, were coming in.

CGAS Elizabeth City was directed to launch aircraft for Inland Flood Relief Operations in the vicinity of Tarboro NC. In response, the Air Station called in all available crews, and by 2200 had begun the rescue of thousands stranded by the floodwaters. While the initial response was not unusual, the sustained effort that followed for the next 42 hours was.

It was an extraordinary effort, in part because the Coast Guard’s primary duty is to respond to calls for help on the high seas. Inland Search and Rescue (SAR) is normally the responsibility of the US Air Force. (USAF.) Due to the extraordinary circumstances that occurred with the passage of Hurricane Floyd, the Coast Guard answered the call. CGAS Elizabeth City took control of the Inland SAR effort allowing the USAF to implement contingency response plans to handle multiple major inland disasters on the Eastern seaboard. To do this CGAS Elizabeth City assumed the responsibilities of Inland SAR Mission Coordinator for rescue operations in the vicinity of Tarboro, North Carolina at 2300 on 16 Sep 1999.

As the SAR Mission Coordinator, Air Station Elizabeth City coordinated and executed inland search and rescue efforts in the flood area for 42 hours, directly saving or assisting over 2200 lives. To do this the Air Station took control of aircraft and personnel from seven Coast Guard Aviation commands and twelve Department of Defense (DOD) activities. The DOD participants saved or assisted 1800 people. DOD heavy lift helicopters allowed the rapid recovery of large numbers of people, at times entire communities. This was possible when a suitable landing site was found, allowing the DOD helicopters to land and load hundreds of victims at once. This left the task of hoisting and rescuing those trapped in inaccessible areas amongst trees and power lines mainly to the Coast Guard hoist equipped helicopters.

To coordinate and safely execute this effort, the Coast Guard put in place air and ground control procedures. The airborne effort was completed by Coast Guard HC-130H aircraft serving as the On-Scene Commander (OSC). A Coast Guard HC-130H was on station from 2311 on the 16th until the responsibility was transferred to the USAF at 1700 on the 18th. At times the HC-130H was directly controlling over 30 aircraft conducting SAR or other relief operations. In addition, they had full control of the airspace over the flood zone and coordinated requests to enter the area with the FAA. In order to ensure safety, the Navy provided airborne radar equipped E-2C Hawkeyes which gave the Coast Guard’s OSC a radar picture of all aircraft allowing the largest Inland SAR cases in recent history to be completed safely. Ground operations were coordinated and executed by Air Station personnel forward deployed directly to the landing zones and Emergency Operations Centers. This allowed recovered personnel to be processed quickly and reports of distress received by local authorities to be passed efficiently to the OSC for execution. The Coast Guard had at least one officer in each Landing Zone from the start of operations until it handed off to the USAF. In addition, the Coast Guard provided other personnel & equipment. One key piece of equipment was a Transportable Communications Center or TCC. The TCC and those that operated it were indispensable. They provided a direct communications link between the officials on the ground in the flood zone and the On Scene Commander. Additional Coast Guard personnel and deployable rescue boats from across the country were dispatched providing humanitarian assistance. These men and women worked around the clock in an austere environment to provide humanitarian assistance to those in need.

The performance of the Coast Guard aircrews was outstanding. A few of many examples is as follows.:

On the night of 17 September, LCDR Paul Franklin and crew located two tractor trailer drivers trapped in the cabs of their rigs in swiftly moving, rising flood waters. As pilot at the controls Franklin effected direct deployments of rescue swimmer Paul Lansing to pull the men from their vehicles to the cabin of Coast Guard helicopter 6026. Petty Officer Lansing was deployed dangerously close to trees and powerlines to the cabs of both trucks and used the rescue strop to bring both survivors into the helicopter. On his second and third sorties he assisted the flight mechanic in recovering by basket 22 people from the porch of a house completely surrounded by rising flood waters. Franklin delivered them to a makeshift landing zone on NC highway 64. Flying until the dawn, LCDR Franklin and crew continued to hoist flood victims from houses, decks, and yards, until fuel and fatigue, generated by flight and hover operations in an extremely dangerous environment required his return to Elizabeth City. At one time, LCDR Franklin held 16 persons in the cabin of HH60J, CG6026. Called upon to return later that night, LCDR Franklin flew seven hours through fog and darkness to affect the rescue of 23 more people and deliver them to safety.

LTJG Craig Neubecker and crew were tasked to rescue survivors trapped in a flooded trailer park, The trailer park was well designed for the occupants but not for helicopter operations. Landing within 20 feet of trees, powerlines, trailers, on multiple occasions, rescued over 30 victims from the area. After transporting them to safety, he overheard a Coast Guard H-65 that had located 17 people trapped in a flooded farm building, quickly determined their position, proceeded to the area and took up a hoisting position next to the building. The area was congested with trees, powerlines within ten feet of the aircraft, and a 100’ tower directly off the nose. As the crew hoisted eight survivors from amongst the fuel tanks upset by the raging current, he directed another air asset into position to save the remaining six lives. Alternately flying and navigating, Craig, continued to fly from one distress sight to another, avoiding powerlines, towers, trees, and other aircraft and landing in locations with less than half a rotor disk clearance. On this day, Craig and crew flew a total of eight hours and saved 100 lives. On the night of 18th, Craig once again launched. Under low illumination, utilizing Night Vision Goggles, he expertly piloted the helicopter to an unlit confined area surrounded by high trees and crossed by powerlines and fences. Craig and crew rescued 13 survivors and transported them to safety, and then again rescued two additional survivors on a separate sortie. Flying both day and night, Craigs actions and adept aeronautical skills were instrumental in the lifesaving rescues of 115 persons.

Lieutenant Commander Michael Megan and crew rescued victims from the catastrophic flooding in eastern North Carolina. On the morning of 17 September, with LCDR Megan and crew departed Elizabeth City, enroute to the Tar River area to the intensifying flood relief efforts, which had begun the night before. Upon arriving, he was quickly tasked with rescuing survivors trapped at a severely flooded trailer park in Dunbar, NC. Lieutenant Commander Megan landed the aircraft within a few feet of trees, powerlines, and trailers, and on multiple sorties, rescued over 30 victims from the area. After transporting the survivors to safety, he overheard a Coast Guard H-65 that had located seventeen people trapped in a flooded farm building surrounded by rapidly rising water. He quickly arrived on scene as the H-65 departed, with 14 survivors still stranded inside. Lieutenant Commander Megan expertly piloted the helicopter into hoisting position next to the building. The area was congested with trees, powerlines within ten feet of the aircraft, and a 100’ tower directly off the nose. Deploying the rescue swimmer into the chest deep water, to help the five adults and three children to the basket, Lieutenant Commander Megan hoisted eight survivors from amongst the fuel tanks upset by the raging current. He then directed other assets to save the remaining six lives. Throughout the day, alternately flying and navigating, Lieutenant Commander Megan expertly maneuvered his helicopter from one distress site to another, avoiding powerlines, towers, trees, and other aircraft, hoisting another survivor to safety, and landing in LZ’s with less than half a rotor disk clearance. On this day, Lieutenant Commander Megan and crew flew eight hours and had saved 100 lives, and additionally the lives of some household pets.

Lieutenant Bish piloted Coast Guard Helicopter CG6026 at times within five feet of high-tension powerlines, to conduct multiple hoists and rescue swimmer deployments to houses and barns surrounded by the rising, turbulent waters. The Tar River rose 45 feet above flood stage, stranding thousands of people and creating a power outage for three counties. The situation demanded that Lieutenant Bish utilize night vision goggles and fly the helicopter in an unfamiliar flight environment dangerously close to trees, powerlines, and unlit towers. Because of his knowledge of the mission and the area, he volunteered to return to the scene despite his fatigue with another aircraft commander. On the second sortie, he served as copilot during the rescue of 35 survivors, all but one hoist conducted at night. Lieutenant Bash’s exceptional aeronautical skills and endurance during 11.7 flight hours were instrumental in the rescue of 49 men, women and children on this first night. On the night of 18 September, Lieutenant Bish, this time as aircraft commander, was once again called to rescue those trapped by the still rising flood waters. Lieutenant Bish and crew used night vision goggles to locate survivors fleeing the water to higher ground.

AST3 Shannon Scaff, a Coast Guard Rescue Swimmer, during the day of 17 September and the night of 18 September, participated in the rescue of 115 men, women, and children during flood relief operations following Hurricane Floyd. On the first day he was deployed by sling and forced to wade through rapidly moving chest deep water to reach eight people stranded in a farm equipment building. The surface of the water was streaked with gasoline from the overturned above ground fuel tanks near the building. He led five adults and carried three children to the hoisting area and assisted them into the rescue basket. Later that day, during eleven different sorties at confined landing zones, surrounded by water, Shannon assisted a total of 91 mostly elderly and non- ambulatory persons into the helo for evacuation. At midafternoon, a levee broke near Tarboro, NC, immediately trapping persons in the water’s path in their homes. Shannon was deployed within 10 feet of powerlines to a submerged porch to rescue a man frantically waving a towel from his flooded house. He used the sling augmented double pick-up technique to hoist the man from the rail of his porch to safety. On the night of 18 September, Shannon was once again called on to participate in flood relief operations. Immediately after arriving on scene in the vicinity of Tarboro, helicopter CG6026 was directed to pick up as many people as possible from the crowd of over 100 stranded persons isolated by rising floodwater. CG6026 landed in a confined and unlit LZ crisscrossed by powerlines and fences, where Shannon assisted 11 adults and carried two children aboard the helo. During the takeoff from the LZ, he was able to calm one of the passengers overcome by fear of flying in the packed cabin.

AST3 Shannon Scaff, a Coast Guard Rescue Swimmer, during the day of 17 September and the night of 18 September, participated in the rescue of 115 men, women, and children during flood relief operations following Hurricane Floyd. On the first day he was deployed by sling and forced to wade through rapidly moving chest deep water to reach eight people stranded in a farm equipment building. The surface of the water was streaked with gasoline from the overturned above ground fuel tanks near the building. He led five adults and carried three children to the hoisting area and assisted them into the rescue basket. Later that day, during eleven different sorties at confined landing zones, surrounded by water, Shannon assisted a total of 91 mostly elderly and non- ambulatory persons into the helo for evacuation. At midafternoon, a levee broke near Tarboro, NC, immediately trapping persons in the water’s path in their homes. Shannon was deployed within 10 feet of powerlines to a submerged porch to rescue a man frantically waving a towel from his flooded house. He used the sling augmented double pick-up technique to hoist the man from the rail of his porch to safety. On the night of 18 September, Shannon was once again called on to participate in flood relief operations. Immediately after arriving on scene in the vicinity of Tarboro, helicopter CG6026 was directed to pick up as many people as possible from the crowd of over 100 stranded persons isolated by rising floodwater. CG6026 landed in a confined and unlit LZ crisscrossed by powerlines and fences, where Shannon assisted 11 adults and carried two children aboard the helo. During the takeoff from the LZ, he was able to calm one of the passengers overcome by fear of flying in the packed cabin.

Epilogue:

This is a glimpse into the response to one of many hurricanes that occur each year. The story was told by relating the actions and accomplishment of a few to convey the competence and dedication of all. Within Coast Guard Aviation, a group kindred spirits, there is a feeling of altruism that makes it the icon of Search and Rescue.

On the Coast Guard Aviation Association History Website there is a Coast Guard Aviation Roll of Valor https://aoptero.org/history/roll-of-valor/ At present there are 965 citations awarded for personal accomplishment ranging from the Coast Guard Commendation Medal to the Silver Star. They tell the story of individual achievement and as a group, provide an insight to Coast Guard Aviation.

My sincere appreciation is extended to CDR Craig Neubecker (Ret) for his extensive first-person contributions to this story.

CGAA Historian

John Moseley