Requesting Emergency Flight Status

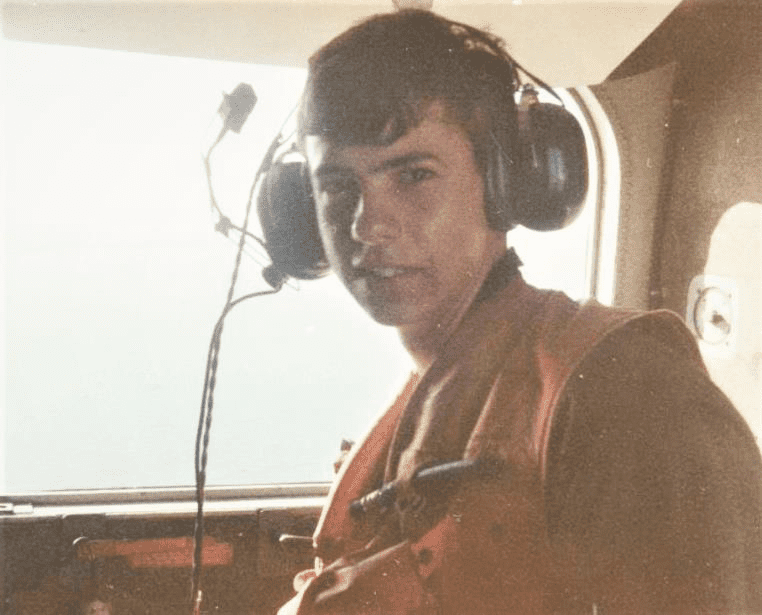

by Larry L French, AT2 (1966-1970)

Copyright © 7-2022 Larry L. French

We were flying in a HU16 Grumman Albatross, returning from a big search around the island of Grand Turk. As some of the crew members would do, they would stash away some cheap, duty-free rum from the islands. (Initially, one of the main purposes of the Coast Guard was to stop rum running from the islands to the U.S. There is some real humor in the irony of this.) On a long flight, a little rum in the coffee made the trip a little more pleasant. (At least that’s what they told me.)

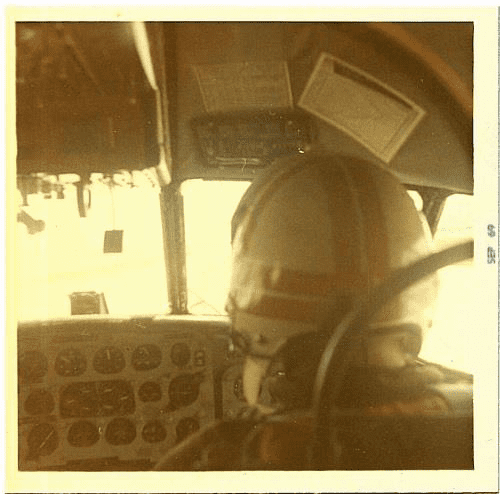

I was the radioman on this flight and the third man in the cockpit; seated right behind the co-pilot. These planes were noisy and we were to always wear earplugs and headset for hearing protection and to communicate with the plane’s intercom system. To the right of the radioman’s seat was a “porthole” shaped window that looked out at starboard wing, the roaring engine and propeller. (For those that don’t know, the Albatross is a two engine plane that can take off and land on water.) About halfway out on the lower side the wing, there was a “drop tank” that was used to carry additional fuel for longer flights. Near the end of each wing was a “float tank” that extended down and was used to help support and stabilize the aircraft when it did water landings.

When it comes to facing a large, severe turbulent storm, we generally dodge them if at all possible. We fly around them. We’ll fly over them. We’ll fly under them but you do not want to fly through them. (These planes are not pressurized and so generally the pilots would stay under ten thousand feet). This was an unusually large storm and we not could find a way around it; so our only choice was to fly through it. As I would observe the altimeter, we would be flying at seven-thousand feet and almost instantly we would drop two or three hundred feet. It was if there were vacuums in the sky where there was no air to give the plane lift. What a roller-coaster ride!

After strapping down in my seat, I began to gaze out the “port-hole” window, watching as the wing would fade in and out of sight because of the thickness of the clouds. Now we were really in the “soup” with extremely limited visibility. Even with the use of the radar we had difficulty detecting a path out of this monster storm.

I guess it was a design flaw with these planes; the overhead escape hatch doors were not completely water tight and we had a number of leaks with water coming in the cockpit. This was bad news for a couple of reasons. Most of the avionics (transmitters and receivers) are secured in this area and they do not respond well to being wet. Additionally, it added to the discomfort for the crew members and it also increased the weight of the plane and made handling it even more difficulty. In the meantime some of the crew members were enjoying their stash of rum in their coffee; some a little too much, (if you know what I mean). The flight mechanic was a seasoned ole timer with a lot of experience (with flying and also with drinking.) He would regularly watch the engine analyzer for any irregularities with either engine. Over the last hour he had reported that there was a potential serious problem with the starboard engine. He was generally a pretty laidback guy but now he looked worried. We weren’t sure if we had a problem with the engine or with a mechanic that had a little too much rum and coffee.

As the radioman, one of my jobs was every fifteen minutes to radio our home base, “Miami Air Station” and report “operations normal”. Then Miami Air Station would calmly reply, “Coast Guard Seven-two-two-three, roger your fight operations normal”. Somehow hearing those words brought a little solace. (This experience was like the solider in a foxhole; there were some serious prayers, too.)

Flying blind through these thick clouds; being bounced all over the place; experiencing dripping water and a veteran flight mechanic beginning to panic as he tells us we’ve got a problem with the right engine made this two hour part of the flight seem like an eternity. And then gradually, we saw the clouds begin to loosen-up, the skies became brighter and the rains stopped. Finally we broke out into a beautiful velvet-blue sky. Below was the pale green of the Atlantic Ocean scattered with rainbow colored coral reefs. There was a sense of relief; “we’re going to make it”. Unfortunately, it was a premature sigh of relief.

Before completing our sigh of relief, the right generator warning light lit up the instrument panel. I then contacted the base, “Miami Air, Miami Air, this is Coast Guard Seven-two-two-three. Be advised we have an indication that our right generator has failed. Our position is four zero miles southeast of Nassau. Over.” Miami answered, Coast Guard Seven-two-two-three, this is Miami Air, roger.”

By the time I had completed my communications with Miami, the pilots decided that because there were chunks of metal, oil and amber sparks streaming from the cowling, they should “feather” (shut down) the right engine. I again contacted Miami Air and reported we had shut down one of our engines. Miami’s response was “Are you requesting emergency flight status”? When I passed this question on to our pilot, he said “tell them hell no, we always fly like this!” He quickly stopped me and said, “No, no, don’t say that. Tell them our location and yes to the emergency flight status”.

The plane has an auxiliary power unit (APU) in the tail section of the plane to provide electricity for the plane when the engine generators are shut down. To reduce the strain on the left engine and augment the supply of electricity, the crew in the rear of the plane started the APU. Then to everyone’s shock, an announcement came from the rear of the plane that the APU had just caught on fire and it had to be secured immediately (shut down). The fire was quickly extinguished and everything was back to – well, not exactly normal, but we were still airborne.

The noise from the roaring engines was reduced by half but in a situation like this what’s a little noise? These planes were designed to fly on two engines and we were steadily losing altitude. It felt like Nassau was four-hundred miles away. At last we could see the island and the runway. I can’t remember when a landing strip has ever looked so good. Red flashing lights lined both sides of the runway indicating that rescue equipment was there. But there was one more serious problem; “how do you stop the plane?”

Once the plane touches down, these planes are slowed down by the combination of brakes and reversing the propellers on the engines. Now that one engine has been shut down, reversing the props is no longer an option. Knowing the brakes could possibly overheat and the wheels could ignite, we were told, “as soon as the plane stops, get out as quickly as possible and get away from the plane!” The pilots applied their full force to brakes. Black smoke billowed out from around the wheels and landing gears, to the point that the brakes almost ignited. I’m glad to report everyone got out safely. We were all rattled but so grateful to have our feet on the ground once again, safe and sound.

(This story was originally written for my freshmen English class in 1970, shortly after my time in the CG.)

Larry would really like to hear from some of you that remember those days – his email is: [email protected]