An Amazing Christmas Story

By Pteros Al Allison, Aviator 885, and Roger

Schmidt, P-2729, a Member of the Flight Crew

Through the light rain and low clouds, the pilot of a Coast Guard C-130 saw a Navy P-3 directly ahead. There was no time to react—the next instant, there was a mid-air collision 200nm NE of Midway Island. The date was 12 DECEMBER, 1971!

AL: In December 1971, I was a LCDR stationed at Air Station BARBERS POINT.

I was a C-130 Aircraft Commander and the unit Flight Safety Officer. The dates are my best estimates using my flight log book and my fading memory of the events surrounding the sinking and search for survivors of the Herring Kirse, a Danish freighter, that sank in 50-60 kt winds and 30-40 ft seas about 200 nm NE of Midway, and the subsequent mid-air collision between a Navy P-3 and the CG C-130B 1348.

Part One: The Heering Kirse had left Mexico for Japan with a load of maize. It ran into high winds and rough seas while passing northeast of Midway Island. It developed a leak in one hold, which resulted in a severe list. The captain issued an SOS probably on 9 DECEMBER. My logbook shows an 8.3 hour flight on the 10th which was about a five hour flight from Barbers Point to the search area off Midway Island, followed by a three hour search and subsequent landing at Midway. There was no further radio contact with the ship, so it was assumed it had sunk, and the search now was for any survivors.

A search and rescue command post was set up at Midway. The search aircraft included three USCG C-130s, a Navy P-3, and an Air Force C-130. About eight air-craft were involved. My logbook does not show a flight for me on 11 December.

ROGER: AirSta San Francisco dis-patched a double-crewed (less navigators) C-130 (the 1348) to assist in the search. I, then an ATC, assigned myself to one crew because I had a Navy friend from my tour in Naples who was stationed on Midway. One crew flew the leg from San Francisco to Hawaii; the second crew was scheduled for the next day’s search. Flight Engineer Lou Sliter and I spent the evening before the flight at my Navy friend, Norman El-liott’s house. I asked Norman if he would like to come along on the search the next morning. He agreed (a decision I’m sure he regretted).

AL: On 12 December, the weather was poor—light rain and low visibility. The search aircraft (maybe six) were assigned specific adjoining search areas with start-ing points 60 miles apart. I was assigned an area as were two other CG C-130s, including the 1348.

ROGER: Navigators were to be as-signed from personnel assigned from Barbers Point. On the morning of the search, the navigator for my aircraft was pulled from our crew and assigned to a “command post” set up on Midway Island I was the 1st Radioman on my flight and assumed the duties of navigator. This was not unusual; the Coast Guard had been using senior Radiomen as navigators for many years—even though they were never given any formal training. The Radiomen just picked up the information as they went along, usually because they were proficient at operating some of the not “user friendly” early Loran equipment. The 1348 departed Midway to the search area the morning of 12 December. Electronic navigation aids were virtually non-existent in our search area. In addition, our Doppler equipment was unreliable. All I had to work with was the Doppler computer, which normally took the input from the Doppler radar, but the Doppler radar was in-operable. I could operate the Doppler computer manually and enter headings and way-points, and thereby provide us with some navigation ability. However, enroute to our search area, I discovered that the Doppler computer had a fixed 29o E error. In the course of the post-mid-air investigation, it was discovered that a servo had been improperly installed. This was not a problem as long as I knew about it and compensated for it.

There were four search areas assigned: F-1 thru F-4. They formed a box about 200 miles square. The 1348 was assigned area F-2, which was in the Northeast corner of the 200 square mile box. Because of the lack of navigation aids on board, we asked another CG aircraft for a fix and a steer to the start point of our search area. We began in the SE corner of F-2. Subsequent to the mid-air, it was determined that we had been sent to a start point that was about 15 miles to the West of where we should have started. I set up the Doppler computer for a creeping search from the southeastern border of our area, with north-south legs, spaced one mile apart. In other words, we would fly to the northern boundary, turn West for one mile, then fly south to the southern boundary, then west for one mile, and so on. The aircraft in the adjacent search areas were assigned different search altitudes. We had an assigned altitude of 500’. The P-3B assigned to the area west of ours was as-signed an altitude of 750’. However, on scene weather was heavy overcast with the bases at 500’. Since you can’t see through the clouds, most of the aircraft ended up searching at 500’.

When the 1348 entered F-2, it shut down the outboard engines to save fuel, and began the search. With regard to aircraft separation, we were most concerned with the aircraft in the area to our south (F-4); that aircraft would be flying his north leg while we were flying our south leg. Both aircraft were equipped with TAC-AN. (Tactical Air Navigation). Normally, this equipment pro-vides bearing and distance to a TACAN station. However, when it is used between aircraft, it only gives you a distance to the other aircraft, not a bearing. When used this way, it requires coordination between the two aircraft to set their TACANs to 63 channels apart. For example, one aircraft would go to channel 7 the other to channel 70 and the two sets would lock up with each other, giving the distance between them. We established an air to air TACAN lock with the aircraft to the south so we could constantly monitor our separation. Unfortunately, the air-to-air capability is limited to just two aircraft at a time, so there was no way for us to determine separation with the aircraft in areas F-1 and F-3.

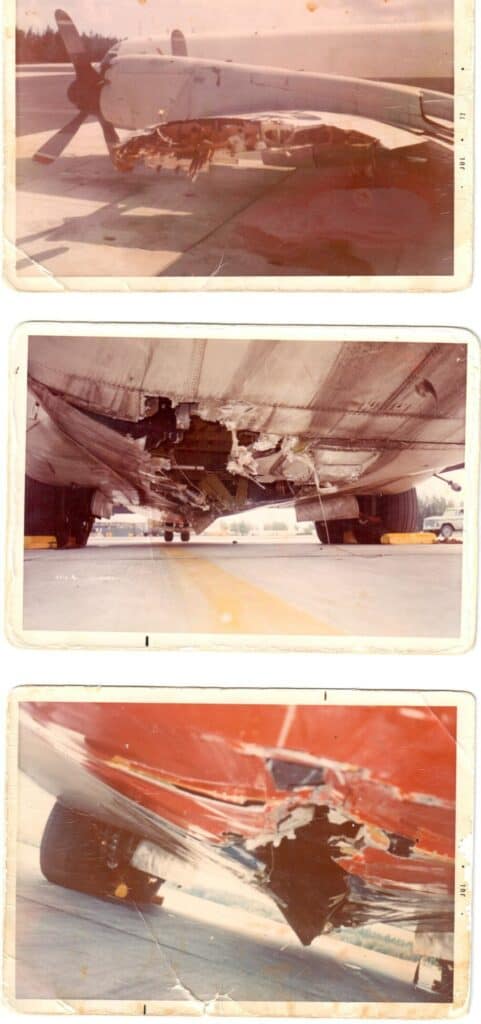

After about three hours of searching, we were approaching the southern end of our area. The Aircraft Commander (Matt) sitting in the right seat, asked me how far to our turn.

I showed about three miles to go. He said, ‘I’m going to turn now, we have a 13 mile lock on the other aircraft and that’s close enough.’ At this point, we were flying at 500’ in and out of the bottoms of ragged clouds. The Aircraft Commander directed the co-pilot flying in the left seat to begin our turn. As soon as he lifted our left wing to start the turn, the P-3 burst out of the cloud flying straight and level right at us. There was no chance of taking any evasive action. The left wing tip of the P-3B contacted the underside of the 1348 just behind the nose wheel and ripped a tear down the entire belly of the aircraft back to the cargo ramp. The vertical stabilizer of the P-3 left a black paint streak across the bottom of our left wing and creased the left aileron. Approximately twelve feet of the outer wing of the P-3 was torn off and the cap of its vertical stabilizer dented. After the im-pact, Matt assumed control of the aircraft and initiated a climb to a safer altitude; however, the two outboard engines were shut down. In such a situation, the Flight Engineer would normally begin an emergency air start; however, at first he froze, then recovered and slammed the condition levers forward to start the outboards. We did not get ignition on number one. Once number four was on speed, we tried number one again and got a start. We climbed to 5000’ and were intercepted by another CG C-130 and were escorted back to Midway. The return flight was mostly uneventful, though there was some concern about what would happen upon touchdown at Midway. The runway at Midway is relatively short, and there was a strong crosswind, but Matt made a perfect approach and landing. It was later determined that we were about 46 miles further West than we should have been—in other words, we were flying in the P-3’s search area.

AL: We took off from Midway and proceeded to our assigned search area, shut down the outboard engines, lowered the ramp, and commenced the search at 1000 feet above sea level–maybe 1-2 miles visibility in light rain. It was two to three hours into the search when I heard a mayday from one of the Navy P-3s–they had just had a mid-air collision with a Coast Guard C-130!!!–the pilot reported that they had lost about 10 feet of the port wing and fuel was pouring out. He said he had control of the aircraft and was heading back to Midway. We had heard nothing from the CG aircraft (1348) involved in the collision and feared the worst. We continued to broadcast on all frequencies, UHF and HF. AFTER WHAT SEEMED LIKE AN ETERNITY, we finally heard a mayday from the C-130. The wing of the P-3 had hit its belly and wiped out the antennas, but had not penetrated the cargo floor where SOME OF THE CREW were resting on mattresses.

I broadcasted that I was going to intercept the wounded CG aircraft, and escort it back to Midway. After maybe 10-15 minutes, we sighted the 1348, and observed pieces of metal falling away from the fuselage. We took a trailing position and guided the aircraft back to Midway where it landed safely shortly after the P-3 had landed.

It’s still hard to believe that two 125,000 pound aircraft each traveling at 200 knots could run into each other almost head on and survive the collision and land safely without injury to anyone. At the time, I called it the 1971 Christmas miracle!! We got all the crews together that night and had a most memorable celebration.

The search for survivors continued for a few more days. 31 of the 36 crew on the Herring Kirse were rescued by commercial ships in the area. But the other five crew-men were never found, nor was any of the wreckage ever found.

ROGER: There are two types of aircraft accident investigations. The first is an AAB (Accident Analysis Board). In theory, there is blanket immunity for everyone involved in the accident. You can divulge anything you want to the AAB, i.e.; ‘I was so drunk I had no idea where I was,’ and nothing can be held against you. The idea behind the AAB is to discover the cause of the accident and find out if there is anything that can be done to prevent it from happening again.

The second type of investigation is called the Legal Board of Investigation.. Once the Legal Board is convened, they name persons as “parties to the investigation”. If you are named a “Party,” the first thing that you do is get a lawyer. The results of this board CAN be used against you; the Board can recommend that punishment be awarded through a Courts Mar-tial.

A joint CG/Navy AAB was set up at Mid-way Island—literally ‘immediately.’ We climbed off the 1348 and were ushered to the hangar and interviewed by Navy Flight Safety Officers. They determined that an initial error of 11 degrees was set into our computer; that, coupled with the 15 mile error in our starting point, accounted for how we ended up in the wrong search area at the point of impact. In addition, they found the following: 1) Pilot error (Matt)—the Aircraft Commander “failed to maintain positive control over the location of his aircraft under marginal weather condi-tions;” 2) Supervisory: There were too many aircraft assigned to the search area to operate safely; 3) Weather: Ragged ceilings from 500 to 1500 feet and low visibility in scattered rain showers made it impossible to maintain visual clearance; 4) And a bunch of other gob-blygook.

The findings of the AAB were sent to the COs of all the units involved. This included one of the pilots involved in the search, as well as the CO of CGC Chautauqua, the On Scene Commander (OSC).

A Legal Board of Investigation was con-vened on Oahu. Named as “Parties to the in-vestigation” were Matt (the 1348 AC), the pilot of the P-3, me, the CO of the Chautau-qua, and the CO that was one of the pilots in-volved in the search. When the CG learned that some of the “Parties” named in the Legal board had read the AAB, the CG Flight Safety division at HQ demanded that the Legal board be cancelled. They argued that the integrity of the AAB was too important, and, since several of the “Parties” had already read the AAB, there would be no way that they could testify after having had an inside look at the AAB. CGHQ agreed, but the Navy jumped up and said “No way! We have $7 million damage to two aircraft; someone must be held accounta-ble”. Therefore, a Legal Board was convened at Pearl Harbor. We all got our lawyers and proceeded to Hawaii. Once again, the CG ob-jected to the formation of the board, based on the integrity of the AAB. The Board’s reaction was to issue a copy of the AAB to ALL the Parties. They warned us that we could only testify about things that we actually knew, not on things that we had learned by reading the AAB. Try that sometime! That’s like un-ringing a bell. Early in the investiga-tion, I was released. Since I had no “formal” training as a navigator, I could-n’t be held responsible for my actions. I begged my lawyer to throw me under the bus to take some heat off Matt, but they wouldn’t allow it. Since the Board was in a closed session, I had to leave and was never aware of went on afterwards, nor do I know what the final results were, but I’m sure that Matt took a hit because of it.

AL: I was assigned as the flight safety member of the accident investigation board, and we started the process of gath-ering evidence and crewmember testimo-ny. A brief summary of the findings of the board is that the CG aircraft had lost all navigation systems except for Doppler navigation (Doppler Navigation is a self-contained aircraft navigation system that uses Doppler effect radar interaction with the earth in dead-reckoning calculations to navigate.) Although the P-3 and the C-130 HAD STARTED THEIR SEARCH-ES 60 MILES APART, THEY HAD BEEN ASSIGNED THE SAME SEARCH ALTITUDE of 500 feet! The investigation determined that the C-130 navigation was faulty and the aircraft en-tered the search area of the P-3. At some point, out of the low visibility mist, the pilots each saw the other aircraft, but had virtually no time to react, and the wing tip of the P-3 hit the belly of the C-130!

ROGER: Several things happened as a direct result of the accident. Initially, en-listed aircrews were not allowed to serve as navigators. As a result, three pilots had to be assigned to every flight. This proved to be too much of a burden on the AirSta scheduling officers. Consequently, a for-mal Navigator school was established for enlisted aircrews. We now have formally trained enlisted navigators assigned throughout the CG.

All the Navy and Air Force aircraft as-signed to this search were equipped with Inertial Navigation Systems—meanwhile, the CG aircraft depended on outdated navigation systems that were subject to frequent malfunctions. Eventually, INS was procured for CG C-130s. It’s ironic that the professional ’searchers’ were the least well-equipped for searching. It begs the question of ’How can you find some-thing when you don’t know where you are?’ Had we had reliable navigation equipment, for instance INS, this accident would never have happened.

AL: PART TWO: After the investiga-tion was complete, repairs were made to #1348 and I was assigned to fly it back to Barbers Point. The flight had to be made at low altitude because damage to the fuselage made it impossible to pressurize the aircraft. Since it was only a five hour flight, there was plenty of fuel for the low altitude return.

After more maintenance on the aircraft at Barber’s Point, it was ready to be ferried to AirSta San Francisco where it would eventually be taken to Lockheed for the fuselage repair. I was selected to ferry the 1348 to San Francisco. This flight required more careful planning as it was a nearly eight hour flight and the aircraft could still not be pressurized for the more fuel efficient high altitude flight. So, I decided to fly at 18,000 feet, unpressurized, with all crewmembers on oxygen. On 21 January, 1972, we took off — the entire crew had been pre breathing oxygen for about 15 minutes before liftoff with the exception of the flight engineer who had to go off oxygen to inspect a faulty APU generator. He was slightly overweight.

After completing his inspection, he came back aboard and put his oxygen mask back on. We climbed to cruising altitude and the flight was going smoothly until about halfway to San Fran the flight engineer started complaining about having a headache, and a bit later started to complain of vision problems. We checked his oxygen supply which was ok and eliminated hypoxia and hyper ventilation as possible causes of his symptoms. We took him from the flight station and made him as comfortable as possible on a mattress in the cabin. He became quite ill! We called San Fran and asked to talk to a flight surgeon. After analyzing everything about the flight engineer’s symptoms he suspected the flight engineer might be suffering from decompression sickness, commonly referred to as the bends (a medical condition caused by dissolved gases emerging from solution in the blood as bubbles inside the body tissues.

Its effects may vary from joint pain and rashes to paralysis and death)– probably because his OXYGEN PRE BREATHING had been interrupted, because he was overweight, and because we were flying at 18,000 feet unpressurized.

Since the bends can be aggravated by low pressure, I decided to descend to a lower altitude–my best recollection is that we descended to 6,000’. To help conserve fuel at the low altitude, we shut down the outboard engines and continued to our destination, restarting the engines as we approached the mainland. After landing, the flight engineer was taken to a recompression chamber for hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

A couple of days later he was fine and eventually returned to full duty. It was a long saga starting with the mayday call from the Herring Kirse on 9 December and culminating in San Francisco on 21 January–all that were involved in these events would never forget the emotional ups and downs. The moment of terror,

the feelings of relief, the errors made, the professionalism, inter service cooperation– but what I remember best is the pre- Christmas celebration on Midway with all the air crews. What could easily have been a horrendous aviation tragedy turned out to be a “WONDER”—-Something that could have been so bad turned out to be very surprising, beautiful, and amazing! “MIRACLE”–a highly improbable or extraordinary event, or development that brings very welcome consequences!!

A/S San Fran C-130B CGNR 1348 Crew List

PPC: LCDR Matt Ahearn (Right Seat)

CP: LT. John (Kirk) Colvin (Left Seat)

Flight Engineer: (AD1 Louis Sliter)

Navigator: ATC Roger Schmidt

Radio: AT2 David Keene

Scanner: AE3 Dennis K. Nichols

Scanner: AE3 Kenneth T. Roe

Scanner: ASM2 Lawrence Auletta

Schanner (2nd Radio) AT2 Thayer J Seiler

PAX: SFC Elliott (USN)

[The main reason Roger and I wrote this little article was so such an extraordinary aviation event would not totally disappear from our collective memory. It is difficult to describe the emotions on Midway that night–it was relief, it was joyful, it was brotherly love. CG, Navy, and AF pilots had a memorable party celebrating the results of a mid-air collision!!

Roger recently said “I still recall the celebration on Midway. Especially when I approached the P-3 pilot after consuming several adult beverages, looked him straight in the eye and slurred, ‘You look familiar, haven’t I run into you somewhere before?’ I think the club ran out of champagne that night.”

This was as close to a miracle as I know of personally.]

Comments/asides of Ptero Kirk Colvin,

Aviator 1432, HC-130 1348 CP:

On 11 December 1971, I was a thinks-he-knows-it-all 26-year old pilot with 1100+ hours of flight time (possibly the most dangerous point in a young pilot’s career). Twenty-four hours later, I was a realizes-he-doesn’t know-anything pilot who’d just been given a not-so-subtle reminder that he still had a lot to learn about flying—and life.

Because we were double-crewed from SanFran, we lined the center of the cargo compartment with mattresses so the deadheading crew could sleep. After the collision and return to Midway, the mattresses were removed.

Their bottoms looked like they had been machine-gunned. Shrapnel from the collision had in fact penetrated the cargo floor, but was absorbed by the mattresses. If there had been no mattresses, the shrapnel likely would have injured some of the crew back there, and possibly damaged hydraulic lines and control cables.

One theory is that the prop arc of the P-3’s feathered #1 engine went through the prop arc of the 1348’s feathered #1 engine.

Had either one been running, or if the props had contacted each other, things would have turned out differently.

Had the 1348 not begun its turn when it did (in other words, if it had been wings level), the wings of the two aircraft would have collided—and things would have turned out differently.

Had either aircraft been at a slightly different altitude: say, the P-3 a foot higher and the 1348 a foot lower, things would have turned out differently.

Sadly, the Midway Air War (as it came to be called) quickly faded into obscurity. The lessons learned have mostly been forgotten, and will likely have to be relearned the hard way. The loss of HC-130 1705 in 2009 makes it clear that even with the best navigation and the most highly trained crews, bad things can happen.

Ptero Matt Ahearn, Aviator 839, was an exceptional pilot, both FW and RW. As you can probably tell from Roger’s account, he was admired and loved by his

friends (I was one of them). But his career was likely terminated by this event. He was repeatedly passed over for CDR, retired as an LCDR at Elizabeth City, and

passed away in 2011. RIP. Everyone who knew and served with him knew he would have made a great CO—but the Midway Air War made that impossible.

Our flight engineer, Lou Sliter, never did fully recover from the trauma of the midair and his initial failure to execute an immediate emergency air start of the outboard engines. He committed suicide a few months after the mid-air. RIP.

Since I was a lowly LT and not the AC, my career was unaffected by the mid-air. That’s not to say that I wasn’t personally affected. I became a some what paranoid pilot—and I’m glad. I think all professional pilots should be “somewhat paranoid.”

Question everything, ask questions (Why does ATC want me to turn to 270? Why does Approach want me to descend to 2500ft? Why does RCC want me to fly

through extreme icing? (This one actually happened. I said “No.”)) The bottom line is, in Ernest K Gann’s words, “Fate is the Hunter”—so Always Be Prepared.